| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Animals vary in form and function. From a sponge to a worm to a goat, an organism has a distinct body plan that limits its size and shape. Animals’ bodies are also designed to interact with their environments, whether in the deep sea, a rainforest canopy, or the desert. Therefore, a large amount of information about the structure of an organism's body (anatomy) and the function of its cells, tissues and organs (physiology) can be learned by studying that organism's environment.

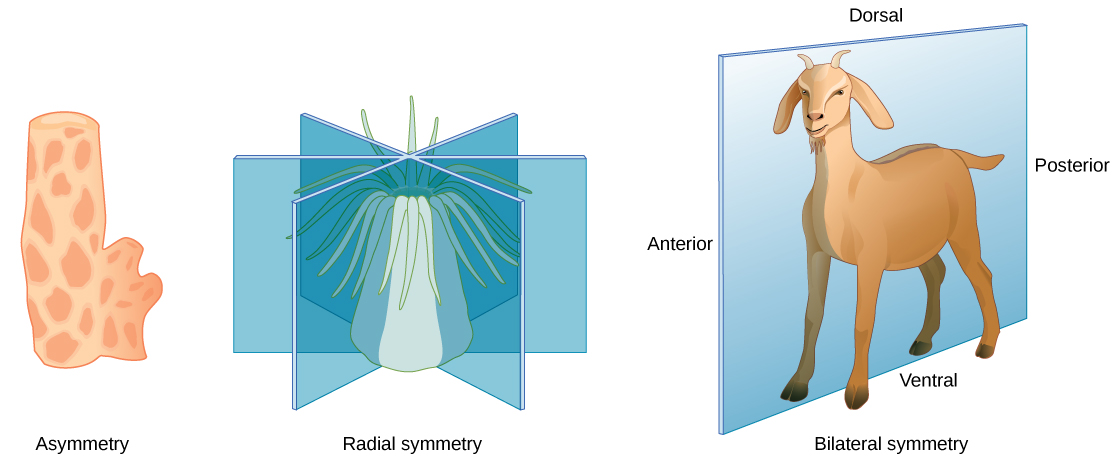

Animal body plans follow set patterns related to symmetry. They are asymmetrical, radial, or bilateral in form as illustrated in [link] . Asymmetrical animals are animals with no pattern or symmetry; an example of an asymmetrical animal is a sponge. Radial symmetry, as illustrated in [link] , describes when an animal has an up-and-down orientation: any plane cut along its longitudinal axis through the organism produces equal halves, but not a definite right or left side. This plan is found mostly in aquatic animals, especially organisms that attach themselves to a base, like a rock or a boat, and extract their food from the surrounding water as it flows around the organism. Bilateral symmetry is illustrated in the same figure by a goat. The goat also has an upper and lower component to it, but a plane cut from front to back separates the animal into definite right and left sides. Additional terms used when describing positions in the body are anterior (front), posterior (rear), dorsal (toward the back), and ventral (toward the stomach). Bilateral symmetry is found in both land-based and aquatic animals; it enables a high level of mobility.

Animals with bilateral symmetry that live in water tend to have a fusiform shape: this is a tubular shaped body that is tapered at both ends. This shape decreases the drag on the body as it moves through water and allows the animal to swim at high speeds. [link] lists the maximum speed of various animals. Certain types of sharks can swim at fifty kilometers an hour and some dolphins at 32 to 40 kilometers per hour. Land animals frequently travel faster, although the tortoise and snail are significantly slower than cheetahs. Another difference in the adaptations of aquatic and land-dwelling organisms is that aquatic organisms are constrained in shape by the forces of drag in the water since water has higher viscosity than air. On the other hand, land-dwelling organisms are constrained mainly by gravity, and drag is relatively unimportant. For example, most adaptations in birds are for gravity not for drag.

| Maximum Speed of Assorted Land Marine Animals | ||

|---|---|---|

| Animal | Speed (kmh) | Speed (mph) |

| Cheetah | 113 | 70 |

| Quarter horse | 77 | 48 |

| Fox | 68 | 42 |

| Shortfin mako shark | 50 | 31 |

| Domestic house cat | 48 | 30 |

| Human | 45 | 28 |

| Dolphin | 32–40 | 20–25 |

| Mouse | 13 | 8 |

| Snail | 0.05 | 0.03 |

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Bmcc 103 - concepts of biology' conversation and receive update notifications?