| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

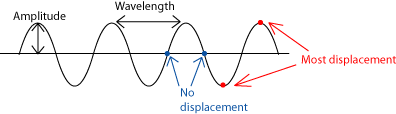

Both transverse and longitudinal waves cause a displacement of something: air molecules, for example, or the surface of the ocean. The amount of displacement at any particular spot changes as the wave passes. If there is no wave, or if the spot is in the same state it would be in if there was no wave, there is no displacement. Displacement is biggest (furthest from "normal") at the highest and lowest points of the wave. In a sound wave, then, there is no displacement wherever the air molecules are at a normal density. The most displacement occurs wherever the molecules are the most crowded or least crowded.

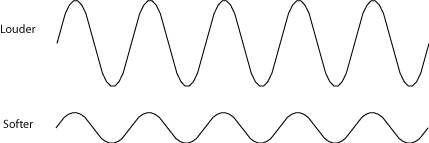

The amplitude of the wave is a measure of the displacement: how big is the change from no displacement to the peak of a wave? Are the waves on the lake two inches high or two feet? Are the air molecules bunched very tightly together, with very empty spaces between the waves, or are they barely more organized than they would be in their normal course of bouncing off of each other? Scientists measure the amplitude of sound waves in decibels . Leaves rustling in the wind are about 10 decibels; a jet engine is about 120 decibels.

Musicians call the loudness of a note its dynamic level . Forte (pronounced "FOR-tay") is a loud dynamic level; piano is soft. Dynamic levels don't correspond to a measured decibel level. An orchestra playing "fortissimo" (which basically means "even louder than forte") is going to be quite a bit louder than a string quartet playing "fortissimo". (See Dynamics for more of the terms that musicians use to talk about loudness.) Dynamics are more of a performance issue than a music theory issue, so amplitude doesn't need much discussion here.

The aspect of evenly-spaced sound waves that really affects music theory is the spacing between the waves, the distance between, for example, one high point and the next high point. This is the wavelength , and it affects the pitch of the sound; the closer together the waves are, the higher the tone sounds.

All sound waves are travelling at about the same speed - the speed of sound. So waves with a shorter wavelength arrive (at your ear, for example) more often (frequently) than longer waves. This aspect of a sound - how often a peak of a wave goes by, is called frequency by scientists and engineers. They measure it in hertz , which is how many peaks go by per second. People can hear sounds that range from about 20 to about 17,000 hertz.

The word that musicians use for frequency is pitch . The shorter the wavelength, the higher the frequency, and the higher the pitch, of the sound. In other words, short waves sound high; long waves sound low. Instead of measuring frequencies, musicians name the pitches that they use most often. They might call a note "middle C" or "second line G" or "the F sharp in the bass clef". (See Octaves and Diatonic Music and Tuning Systems for more on naming specific frequencies.) These notes have frequencies (Have you heard of the "A 440" that is used as a tuning note?), but the actual frequency of a middle C can vary a little from one orchestra, piano, or performance, to another, so musicians usually find it more useful to talk about note names.

Most musicians cannot name the frequencies of any notes other than the tuning A (440 hertz). The human ear can easily distinguish two pitches that are only one hertz apart when it hears them both, but it is the very rare musician who can hear specifically that a note is 442 hertz rather than 440. So why should we bother talking about frequency, when musicians usually don't? As we will see, the physics of sound waves - and especially frequency - affects the most basic aspects of music, including pitch , tuning , consonance and dissonance , harmony , and timbre .

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Understanding your french horn' conversation and receive update notifications?