| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

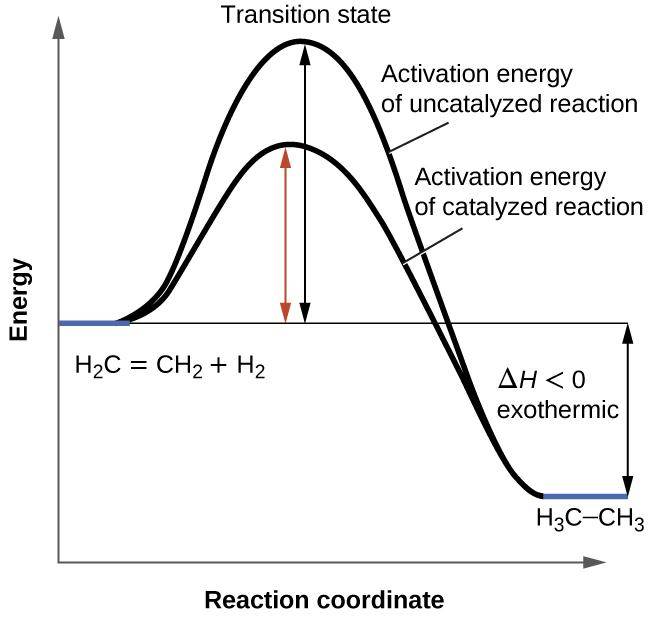

We have seen that the rate of many reactions can be accelerated by catalysts. A catalyst speeds up the rate of a reaction by lowering the activation energy; in addition, the catalyst is regenerated in the process. Several reactions that are thermodynamically favorable in the absence of a catalyst only occur at a reasonable rate when a catalyst is present. One such reaction is catalytic hydrogenation, the process by which hydrogen is added across an alkene C=C bond to afford the saturated alkane product. A comparison of the reaction coordinate diagrams (also known as energy diagrams) for catalyzed and uncatalyzed alkene hydrogenation is shown in [link] .

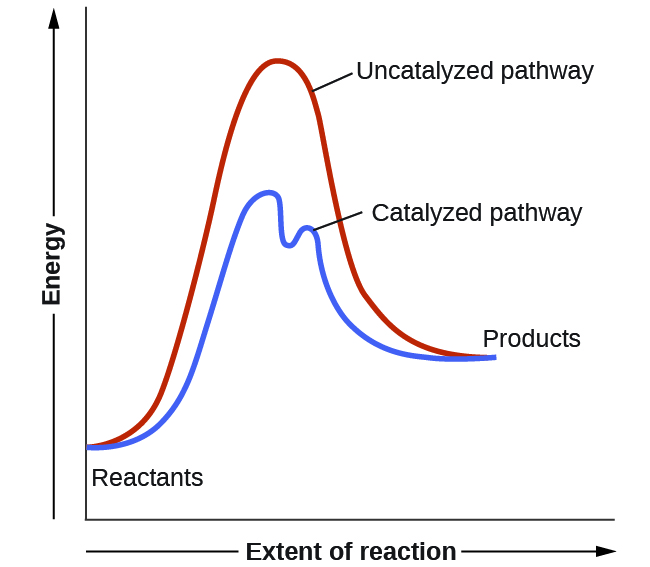

Catalysts function by providing an alternate reaction mechanism that has a lower activation energy than would be found in the absence of the catalyst. In some cases, the catalyzed mechanism may include additional steps, as depicted in the reaction diagrams shown in [link] . This lower activation energy results in an increase in rate as described by the Arrhenius equation. Note that a catalyst decreases the activation energy for both the forward and the reverse reactions and hence accelerates both the forward and the reverse reactions . Consequently, the presence of a catalyst will permit a system to reach equilibrium more quickly, but it has no effect on the position of the equilibrium as reflected in the value of its equilibrium constant (see the later chapter on chemical equilibrium).

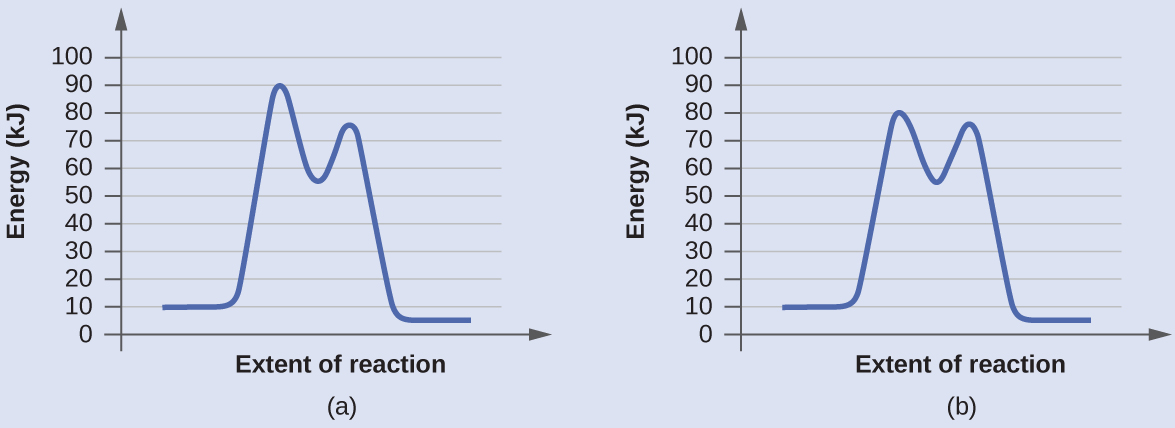

Diagram (b) is a catalyzed reaction with an activation energy of about 70 kJ.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Ut austin - principles of chemistry' conversation and receive update notifications?