| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Single protist cells range in size from less than a micrometer to the 3-meter lengths of the multinucleate cells of the seaweed Caulerpa . Protist cells may be enveloped by animal-like cell membranes or plant-like cell walls. Others are encased in glassy silica-based shells or wound with pellicles of interlocking protein strips. The pellicle functions like a flexible coat of armor, preventing the protist from being torn or pierced without compromising its range of motion.

The majority of protists are motile, but different types of protists have evolved varied modes of movement. Some protists have one or more flagella, which they rotate or whip. Others are covered in rows or tufts of tiny cilia that they beat in coordination to swim. Still others send out lobe-like pseudopodia from anywhere on the cell, anchor the pseudopodium to a substrate, and pull the rest of the cell toward the anchor point. Some protists can move toward light by coupling their locomotion strategy with a light-sensing organ.

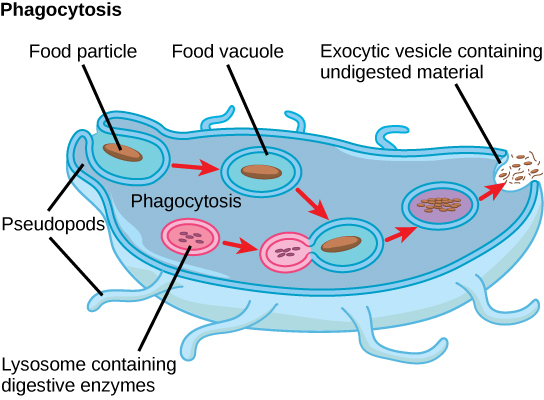

Protists exhibit many forms of nutrition and may be aerobic or anaerobic. Photosynthetic protists (photoautotrophs) are characterized by the presence of chloroplasts. Other protists are heterotrophs and consume organic materials (such as other organisms) to obtain nutrition. Amoebas and some other heterotrophic protist species ingest particles by a process called phagocytosis, in which the cell membrane engulfs a food particle and brings it inward, pinching off an intracellular membranous sac, or vesicle, called a food vacuole ( [link] ). This vesicle then fuses with a lysosome, and the food particle is broken down into small molecules that can diffuse into the cytoplasm and be used in cellular metabolism. Undigested remains ultimately are expelled from the cell through exocytosis.

Some heterotrophs absorb nutrients from dead organisms or their organic wastes, and others are able to use photosynthesis or feed on organic matter, depending on conditions.

Protists reproduce by a variety of mechanisms. Most are capable some form of asexual reproduction, such as binary fission to produce two daughter cells, or multiple fission to divide simultaneously into many daughter cells. Others produce tiny buds that go on to divide and grow to the size of the parental protist. Sexual reproduction, involving meiosis and fertilization, is common among protists, and many protist species can switch from asexual to sexual reproduction when necessary. Sexual reproduction is often associated with periods when nutrients are depleted or environmental changes occur. Sexual reproduction may allow the protist to recombine genes and produce new variations of progeny that may be better suited to surviving in the new environment. However, sexual reproduction is also often associated with cysts that are a protective, resting stage. Depending on their habitat, the cysts may be particularly resistant to temperature extremes, desiccation, or low pH. This strategy also allows certain protists to “wait out” stressors until their environment becomes more favorable for survival or until they are carried (such as by wind, water, or transport on a larger organism) to a different environment because cysts exhibit virtually no cellular metabolism.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Natural history supplemental' conversation and receive update notifications?