| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

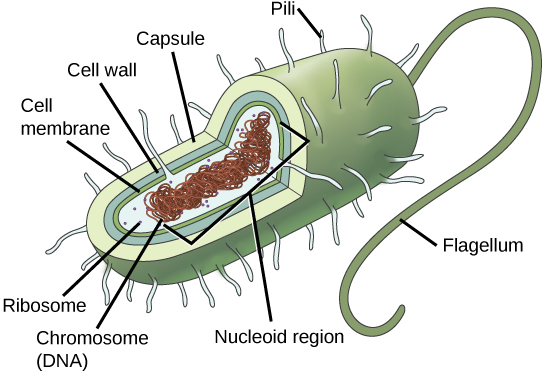

Before discussing the steps a cell must undertake to replicate, a deeper understanding of the structure and function of a cell’s genetic information is necessary. A cell’s DNA, packaged as a double-stranded DNA molecule, is called its genome . In prokaryotes, the genome is composed of a single, double-stranded DNA molecule in the form of a loop or circle ( [link] ). The region in the cell containing this genetic material is called a nucleoid. Some prokaryotes also have smaller loops of DNA called plasmids that are not essential for normal growth. Bacteria can exchange these plasmids with other bacteria, sometimes receiving beneficial new genes that the recipient can add to their chromosomal DNA. Antibiotic resistance is one trait that often spreads through a bacterial colony through plasmid exchange.

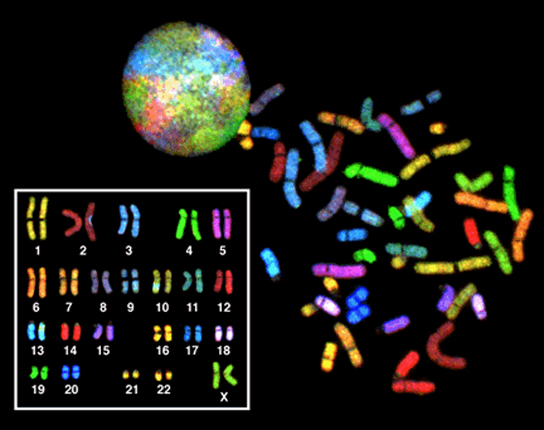

In eukaryotes, the genome consists of several double-stranded linear DNA molecules ( [link] ). Each species of eukaryotes has a characteristic number of chromosomes in the nuclei of its cells. Human body cells have 46 chromosomes, while human gametes (sperm or eggs) have 23 chromosomes each. A typical body cell, or somatic cell, contains two matched sets of chromosomes, a configuration known as diploid . The letter n is used to represent a single set of chromosomes; therefore, a diploid organism is designated 2 n . Human cells that contain one set of chromosomes are called gametes, or sex cells; these are eggs and sperm, and are designated 1n , or haploid .

Matched pairs of chromosomes in a diploid organism are called homologous (“same knowledge”) chromosomes . Homologous chromosomes are the same length and have specific nucleotide segments called genes in exactly the same location, or locus . Genes, the functional units of chromosomes, determine specific characteristics by coding for specific proteins. Traits are the variations of those characteristics. For example, hair color is a characteristic with traits that are blonde, brown, or black.

Each copy of a homologous pair of chromosomes originates from a different parent; therefore, the genes themselves are not identical. The variation of individuals within a species is due to the specific combination of the genes inherited from both parents. Even a slightly altered sequence of nucleotides within a gene can result in an alternative trait. For example, there are three possible gene sequences on the human chromosome that code for blood type: sequence A, sequence B, and sequence O. Because all diploid human cells have two copies of the chromosome that determines blood type, the blood type (the trait) is determined by which two versions of the marker gene are inherited. It is possible to have two copies of the same gene sequence on both homologous chromosomes, with one on each (for example, AA, BB, or OO), or two different sequences, such as AB.

Minor variations of traits, such as blood type, eye color, and handedness, contribute to the natural variation found within a species. However, if the entire DNA sequence from any pair of human homologous chromosomes is compared, the difference is less than one percent. The sex chromosomes, X and Y, are the single exception to the rule of homologous chromosome uniformity: Other than a small amount of homology that is necessary to accurately produce gametes, the genes found on the X and Y chromosomes are different.

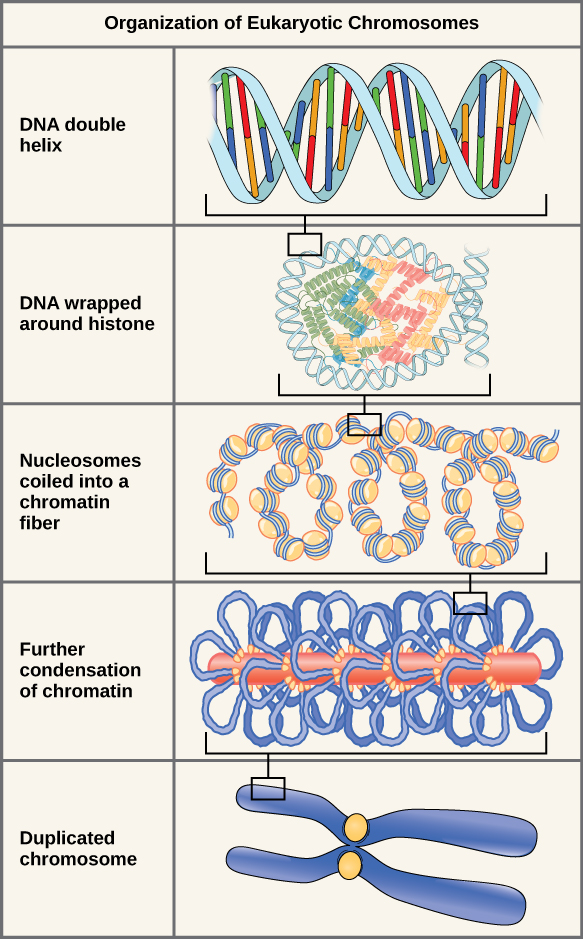

If the DNA from all 46 chromosomes in a human cell nucleus was laid out end to end, it would measure approximately two meters; however, its diameter would be only 2 nm. Considering that the size of a typical human cell is about 10 µm (100,000 cells lined up to equal one meter), DNA must be tightly packaged to fit in the cell’s nucleus. At the same time, it must also be readily accessible for the genes to be expressed. During some stages of the cell cycle, the long strands of DNA are condensed into compact chromosomes. There are a number of ways that chromosomes are compacted.

In the first level of compaction, short stretches of the DNA double helix wrap around a core of eight histone proteins at regular intervals along the entire length of the chromosome ( [link] ). The DNA-histone complex is called chromatin. The beadlike, histone DNA complex is called a nucleosome , and DNA connecting the nucleosomes is called linker DNA. A DNA molecule in this form is about seven times shorter than the double helix without the histones, and the beads are about 10 nm in diameter, in contrast with the 2-nm diameter of a DNA double helix. The next level of compaction occurs as the nucleosomes and the linker DNA between them are coiled into a 30-nm chromatin fiber. This coiling further shortens the chromosome so that it is now about 50 times shorter than the extended form. In the third level of packing, a variety of fibrous proteins is used to pack the chromatin. These fibrous proteins also ensure that each chromosome in a non-dividing cell occupies a particular area of the nucleus that does not overlap with that of any other chromosome (see the top image in [link] ).

DNA replicates during a cell's life. After replication, the chromosomes are composed of two linked sister chromatids . When fully compact, the pairs of identically packed chromosomes are bound to each other by cohesin proteins. The connection between the sister chromatids is closest in a region called the centromere . The conjoined sister chromatids, with a diameter of about 1 µm, are visible under a light microscope. The centromeric region is highly condensed and thus will appear as a constricted area.

This animation illustrates the different levels of chromosome packing.

A genome is all of an organism's DNA. Depending on the type of organism, the DNA can be organized into a single circular chromosome, or multiple, linear chromosomes. One molecule of DNA is a double-stranded piece of deoxyribonucleic acid, and is usually kept condensed in the form of chromatin.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'General biology part i - mixed majors' conversation and receive update notifications?