| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

In this section, we continue to explore the thermal behavior of gases. In particular, we examine the characteristics of atoms and molecules that compose gases. (Most gases, for example nitrogen, , and oxygen, , are composed of two or more atoms. We will primarily use the term “molecule” in discussing a gas because the term can also be applied to monatomic gases, such as helium.)

Gases are easily compressed. Gases expand and contract very rapidly with temperature changes. In addition, you will note that most gases expand at the same rate, or have the same . This raises the question as to why gases should all act in nearly the same way, when liquids and solids have widely varying expansion rates.

The answer lies in the large separation of atoms and molecules in gases, compared to their sizes, as illustrated in [link] . Because atoms and molecules have large separations, forces between them can be ignored, except when they collide with each other during collisions. The motion of atoms and molecules (at temperatures well above the boiling temperature) is fast, such that the gas occupies all of the accessible volume and the expansion of gases is rapid. In contrast, in liquids and solids, atoms and molecules are closer together and are quite sensitive to the forces between them.

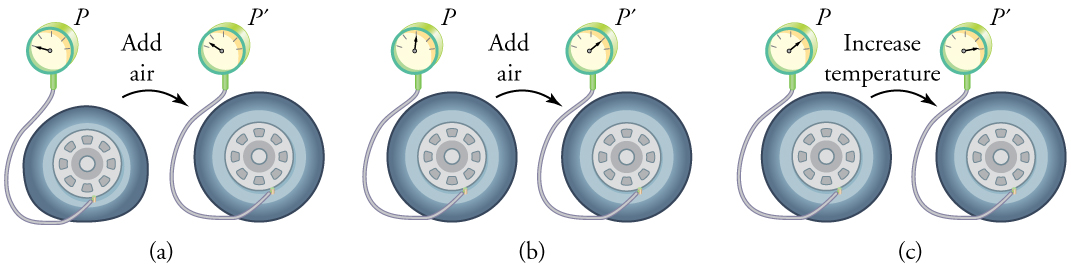

To get some idea of how pressure, temperature, and volume of a gas are related to one another, consider what happens when you pump air into an initially deflated tire. The tire’s volume first increases in direct proportion to the amount of air injected, without much increase in the tire pressure. Once the tire has expanded to nearly its full size, the walls limit volume expansion. If we continue to pump air into it, the pressure increases. The pressure will further increase when the car is driven and the tires move. Most manufacturers specify optimal tire pressure for cold tires. (See [link] .)

At room temperatures, collisions between atoms and molecules can be ignored. In this case, the gas is called an ideal gas, in which case the relationship between the pressure, volume, and temperature is given by the equation of state called the ideal gas law.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Concepts of physics with linear momentum' conversation and receive update notifications?