| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

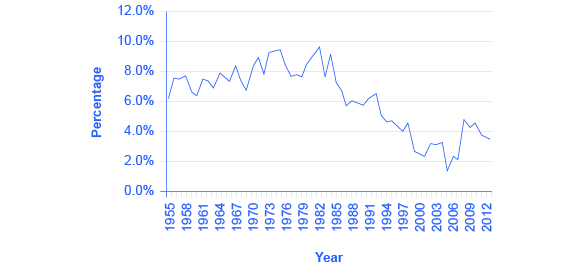

Rates of saving in America have never been especially high, but they seem to have dipped even lower in recent years, as the data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis in [link] show. A decision about how much to save can be represented using an intertemporal budget constraint . Household decisions about the quantity of financial savings show the same underlying pattern of logic as the consumption choice decision and the labor-leisure decision.

The discussion of financial saving here will not focus on the specific financial investment choices, like bank accounts, stocks, bonds, mutual funds, or owning a house or gold coins. The characteristics of these specific financial investments, along with the risks and tradeoffs they pose, are detailed in the Labor and Financial Markets chapter. Here, the focus is saving in total—that is, on how a household determines how much to consume in the present and how much to save, given the expected rate of return (or interest rate), and how the quantity of saving alters when the rate of return changes.

Savings behavior varies considerably across households. One factor is that households with higher incomes tend to save a larger percentage of their income. This pattern makes intuitive sense; a well-to-do family has the flexibility in its budget to save 20–25% of income, while a poor family struggling to keep food on the table will find it harder to put money aside.

Another factor that causes personal saving to vary is personal preferences. Some people may prefer to consume more now, and let the future look after itself. Others may wish to enjoy a lavish retirement, complete with expensive vacations, or to pile up money that they can pass along to their grandchildren. There are savers and spendthrifts among the young, middle-aged, and old, and among those with high, middle, and low income levels.

Consider this example: Yelberton is a young man starting off at his first job. He thinks of the “present” as his working life and the “future” as after retirement. Yelberton’s plan is to save money from ages 30 to 60, retire at age 60, and then live off his retirement money from ages 60 to 85. On average, therefore, he will be saving for 30 years. If the rate of return that he can receive is 6% per year, then $1 saved in the present would build up to $5.74 after 30 years (using the formula for compound interest, $1(1 + 0.06) 30 = $5.74). Say that Yelberton will earn $1,000,000 over the 30 years from age 30 to age 60 (this amount is approximately an annual salary of $33,333 multiplied by 30 years). The question for Yelberton is how much of those lifetime earnings to consume during his working life, and how much to put aside until after retirement. This example is obviously built on simplifying assumptions, but it does convey the basic life-cycle choice of saving during working life for future consumption after retirement.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Openstax microeconomics in ten weeks' conversation and receive update notifications?