| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Go to this site to watch an animation of random sampling and genetic drift in action.

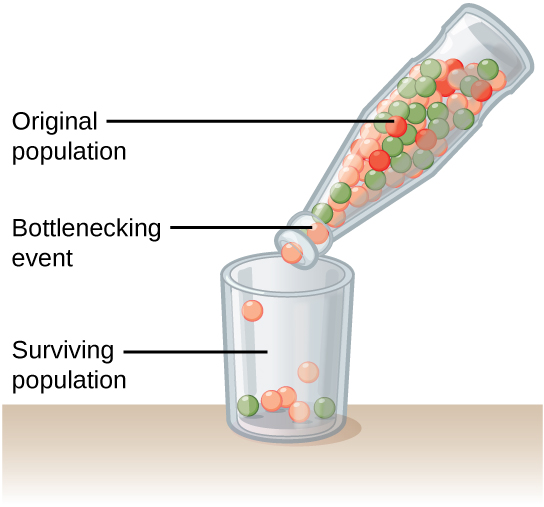

Genetic drift can also be magnified by natural events, such as a natural disaster that kills—at random—a large portion of the population. Known as the bottleneck effect , it results in a large portion of the genome suddenly being wiped out ( [link] ). In one fell swoop, the genetic structure of the survivors becomes the genetic structure of the entire population, which may be very different from the pre-disaster population.

Another scenario in which populations might experience a strong influence of genetic drift is if some portion of the population leaves to start a new population in a new location or if a population gets divided by a physical barrier of some kind. In this situation, those individuals are unlikely to be representative of the entire population, which results in the founder effect. The founder effect occurs when the genetic structure changes to match that of the new population’s founding fathers and mothers. The founder effect is believed to have been a key factor in the genetic history of the Afrikaner population of Dutch settlers in South Africa, as evidenced by mutations that are common in Afrikaners but rare in most other populations. This is likely due to the fact that a higher-than-normal proportion of the founding colonists carried these mutations. As a result, the population expresses unusually high incidences of Huntington’s disease (HD) and Fanconi anemia (FA), a genetic disorder known to cause blood marrow and congenital abnormalities—even cancer. A. J. Tipping et al., “Molecular and Genealogical Evidence for a Founder Effect in Fanconi Anemia Families of the Afrikaner Population of South Africa,” PNAS 98, no. 10 (2001): 5734-5739, doi: 10.1073/pnas.091402398.

Question: How do natural disasters affect the genetic structure of a population?

Background: When much of a population is suddenly wiped out by an earthquake or hurricane, the individuals that survive the event are usually a random sampling of the original group. As a result, the genetic makeup of the population can change dramatically. This phenomenon is known as the bottleneck effect.

Hypothesis: Repeated natural disasters will yield different population genetic structures; therefore, each time this experiment is run, the results will vary.

Test the hypothesis: Count out the original population using different colored beads. For example, red, blue, and yellow beads might represent red, blue, and yellow individuals. After recording the number of each individual in the original population, place them all in a bottle with a narrow neck that will only allow a few beads out at a time. Then, pour 1/3 of the bottle’s contents into a bowl. This represents the surviving individuals after a natural disaster kills a majority of the population. Count the number of the different colored beads in the bowl, and record it. Then, place all of the beads back in the bottle and repeat the experiment four more times.

Analyze the data: Compare the five populations that resulted from the experiment. Do the populations all contain the same number of different colored beads, or do they vary? Remember, these populations all came from the same exact parent population.

Form a conclusion: Most likely, the five resulting populations will differ quite dramatically. This is because natural disasters are not selective—they kill and spare individuals at random. Now think about how this might affect a real population. What happens when a hurricane hits the Mississippi Gulf Coast? How do the seabirds that live on the beach fare?

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Open genetics' conversation and receive update notifications?