| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Ask anyone who lived during the centrally-planned, nonmarket economy years of the Soviet Union—markets are very good at many things. When a product becomes scarcer or more costly to produce we would like to send signals to consumers that would cause them to buy less of that thing. If an input is more valuable when used to produce one good than another, we would like to send signals to firms to make sure that input is put to its best use. If conditions are right, market prices do these useful things and more. Markets distribute inputs efficiently through the production side of the economy: they ensure that plant managers don’t need to hoard inputs and then drive around bartering with each other for the things they need to make their products, and they arrange for efficient quantities of goods to be produced. Markets also distribute outputs among consumers without surpluses, shortages, or large numbers of bathing suits being foisted upon consumers in Siberia.

Economists mean something very specific when they use the word efficient . In general, an allocation is efficient if it maximizes social well-being, or welfare. Traditional economics defines welfare as total net benefits —the difference between the total benefits all people in society get from market goods and services and the total costs of producing those things. Environmental economists enhance the definition of welfare. The values of environmental goods like wildlife count on the “benefit” side of net benefits and damages to environmental quality from production and consumptive processes count as costs.

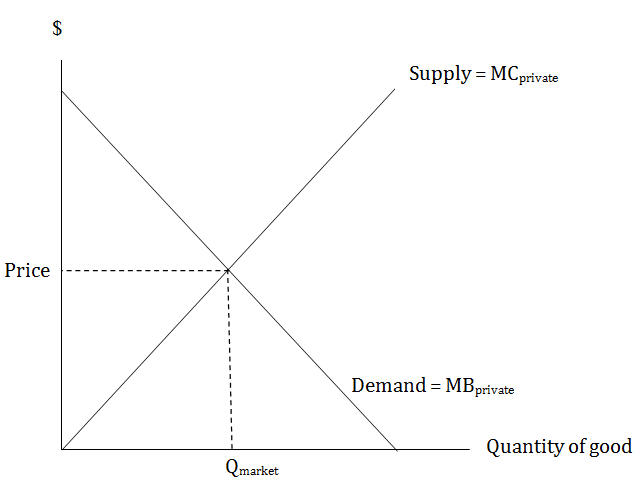

Under ideal circumstances, market outcomes are efficient. In perfect markets for regular goods, goods are produced at the point where the cost to society of producing the last unit, the marginal cost , is just equal to the amount a consumer is willing to pay for that last unit, the marginal benefit , which means that the net benefits in the market are maximized. Regular goods are supplied by industry such that supply is equivalent to the marginal production costs to the firms, and they are demanded by consumers in such a way that we can read the marginal benefit to consumers off the demand curve; when the market equilibrates at a price that causes quantity demanded to equal quantity supplied at that price (Q market in Figure Market Equilibrium ), it is also true that marginal benefit equals marginal cost.

Even depletable resources such as oil would be used efficiently by a well-functioning market. It is socially efficient to use a depletable resource over time such that the price rises at the same rate as the rate of interest. Increasing scarcity pushes the price up, which stimulates efforts to use less of the resource and to invest in research to make “backstop” alternatives more cost-effective. Eventually, the cost of the resource rises to the point where the backstop technology is competitive, and the market switches from the depletable resource to the backstop. We see this with copper; high prices of depletable copper trigger substitution to other materials, like fiber optics for telephone cables and plastics for pipes. We would surely see the same thing happen with fossil fuels; if prices are allowed to rise with scarcity, firms have more incentives to engage in research that lowers the cost of backstop technologies like solar and wind power, and we will eventually just switch.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Sustainability: a comprehensive foundation' conversation and receive update notifications?