| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

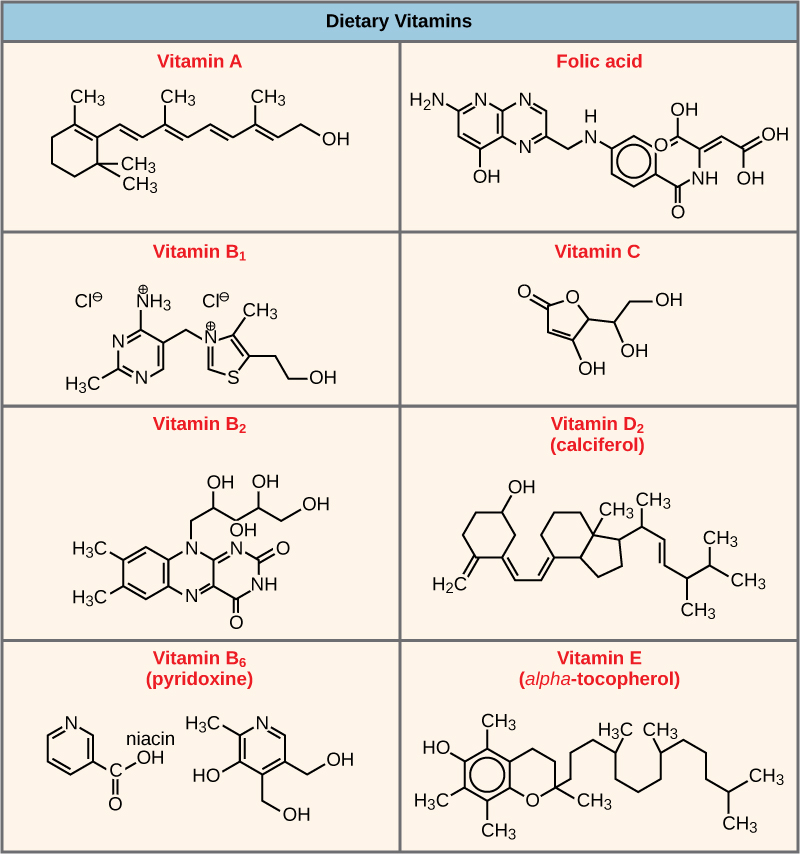

Many enzymes don’t work optimally, or even at all, unless bound to other specific non-protein helper molecules, either temporarily through ionic or hydrogen bonds or permanently through stronger covalent bonds. Two types of helper molecules are cofactors and coenzymes . Binding to these molecules promotes optimal conformation and function for their respective enzymes. Cofactors are inorganic ions such as iron (Fe++) and magnesium (Mg++). One example of an enzyme that requires a metal ion as a cofactor is the enzyme that builds DNA molecules, DNA polymerase, which requires bound zinc ion (Zn++) to function. Coenzymes are organic helper molecules, with a basic atomic structure made up of carbon and hydrogen, which are required for enzyme action. The most common sources of coenzymes are dietary vitamins ( [link] ). Some vitamins are precursors to coenzymes and others act directly as coenzymes. Vitamin C is a coenzyme for multiple enzymes that take part in building the important connective tissue component, collagen. An important step in the breakdown of glucose to yield energy is catalysis by a multi-enzyme complex called pyruvate dehydrogenase. Pyruvate dehydrogenase is a complex of several enzymes that actually requires one cofactor (a magnesium ion) and five different organic coenzymes to catalyze its specific chemical reaction. Therefore, enzyme function is, in part, regulated by an abundance of various cofactors and coenzymes, which are supplied primarily by the diets of most organisms.

In eukaryotic cells, molecules such as enzymes are usually compartmentalized into different organelles. This allows for yet another level of regulation of enzyme activity. Enzymes required only for certain cellular processes can be housed separately along with their substrates, allowing for more efficient chemical reactions. Examples of this sort of enzyme regulation based on location and proximity include the enzymes involved in the latter stages of cellular respiration, which take place exclusively in the mitochondria, and the enzymes involved in the digestion of cellular debris and foreign materials, located within lysosomes.

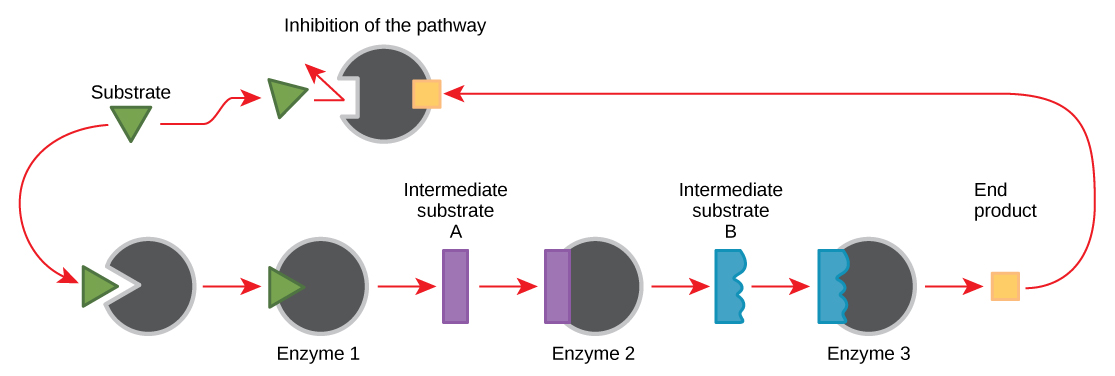

Molecules can regulate enzyme function in many ways. A major question remains, however: What are these molecules and where do they come from? Some are cofactors and coenzymes, ions, and organic molecules, as you’ve learned. What other molecules in the cell provide enzymatic regulation, such as allosteric modulation, and competitive and noncompetitive inhibition? The answer is that a wide variety of molecules can perform these roles. Some of these molecules include pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical drugs, toxins, and poisons from the environment. Perhaps the most relevant sources of enzyme regulatory molecules, with respect to cellular metabolism, are the products of the cellular metabolic reactions themselves. In a most efficient and elegant way, cells have evolved to use the products of their own reactions for feedback inhibition of enzyme activity. Feedback inhibition involves the use of a reaction product to regulate its own further production ( [link] ). The cell responds to the abundance of specific products by slowing down production during anabolic or catabolic reactions. Such reaction products may inhibit the enzymes that catalyzed their production through the mechanisms described above.

The production of both amino acids and nucleotides is controlled through feedback inhibition. Additionally, ATP is an allosteric regulator of some of the enzymes involved in the catabolic breakdown of sugar, the process that produces ATP. In this way, when ATP is abundant, the cell can prevent its further production. Remember that ATP is an unstable molecule that can spontaneously dissociate into ADP. If too much ATP were present in a cell, much of it would go to waste. On the other hand, ADP serves as a positive allosteric regulator (an allosteric activator) for some of the same enzymes that are inhibited by ATP. Thus, when relative levels of ADP are high compared to ATP, the cell is triggered to produce more ATP through the catabolism of sugar.

Enzymes are chemical catalysts that accelerate chemical reactions at physiological temperatures by lowering their activation energy. Enzymes are usually proteins consisting of one or more polypeptide chains. Enzymes have an active site that provides a unique chemical environment, made up of certain amino acid R groups (residues). This unique environment is perfectly suited to convert particular chemical reactants for that enzyme, called substrates, into unstable intermediates called transition states. Enzymes and substrates are thought to bind with an induced fit, which means that enzymes undergo slight conformational adjustments upon substrate contact, leading to full, optimal binding. Enzymes bind to substrates and catalyze reactions in four different ways: bringing substrates together in an optimal orientation, compromising the bond structures of substrates so that bonds can be more easily broken, providing optimal environmental conditions for a reaction to occur, or participating directly in their chemical reaction by forming transient covalent bonds with the substrates.

Enzyme action must be regulated so that in a given cell at a given time, the desired reactions are being catalyzed and the undesired reactions are not. Enzymes are regulated by cellular conditions, such as temperature and pH. They are also regulated through their location within a cell, sometimes being compartmentalized so that they can only catalyze reactions under certain circumstances. Inhibition and activation of enzymes via other molecules are other important ways that enzymes are regulated. Inhibitors can act competitively, noncompetitively, or allosterically; noncompetitive inhibitors are usually allosteric. Activators can also enhance the function of enzymes allosterically. The most common method by which cells regulate the enzymes in metabolic pathways is through feedback inhibition. During feedback inhibition, the products of a metabolic pathway serve as inhibitors (usually allosteric) of one or more of the enzymes (usually the first committed enzyme of the pathway) involved in the pathway that produces them.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Ap biology - part 1: the cell' conversation and receive update notifications?