| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

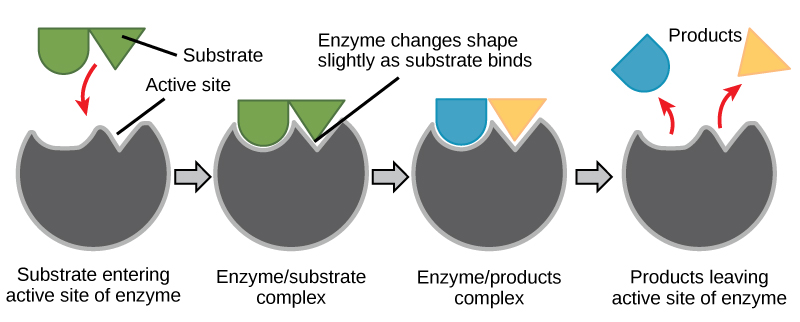

For many years, scientists thought that enzyme-substrate binding took place in a simple “lock-and-key” fashion. This model asserted that the enzyme and substrate fit together perfectly in one instantaneous step. However, current research supports a more refined view called induced fit ( [link] ). The induced-fit model expands upon the lock-and-key model by describing a more dynamic interaction between enzyme and substrate. As the enzyme and substrate come together, their interaction causes a mild shift in the enzyme’s structure that confirms an ideal binding arrangement between the enzyme and the transition state of the substrate. This ideal binding maximizes the enzyme’s ability to catalyze its reaction.

View an animation of induced fit at this website .

When an enzyme binds its substrate, an enzyme-substrate complex is formed. This complex lowers the activation energy of the reaction and promotes its rapid progression in one of many ways. On a basic level, enzymes promote chemical reactions that involve more than one substrate by bringing the substrates together in an optimal orientation. The appropriate region (atoms and bonds) of one molecule is juxtaposed to the appropriate region of the other molecule with which it must react. Another way in which enzymes promote the reaction of their substrates is by creating an optimal environment within the active site for the reaction to occur. Certain chemical reactions might proceed best in a slightly acidic or non-polar environment. The chemical properties that emerge from the particular arrangement of amino acid residues within an active site create the perfect environment for an enzyme’s specific substrates to react.

You’ve learned that the activation energy required for many reactions includes the energy involved in manipulating or slightly contorting chemical bonds so that they can easily break and allow others to reform. Enzymatic action can aid this process. The enzyme-substrate complex can lower the activation energy by contorting substrate molecules in such a way as to facilitate bond-breaking, helping to reach the transition state. Finally, enzymes can also lower activation energies by taking part in the chemical reaction itself. The amino acid residues can provide certain ions or chemical groups that actually form covalent bonds with substrate molecules as a necessary step of the reaction process. In these cases, it is important to remember that the enzyme will always return to its original state at the completion of the reaction. One of the hallmark properties of enzymes is that they remain ultimately unchanged by the reactions they catalyze. After an enzyme is done catalyzing a reaction, it releases its product(s).

It would seem ideal to have a scenario in which all of the enzymes encoded in an organism’s genome existed in abundant supply and functioned optimally under all cellular conditions, in all cells, at all times. In reality, this is far from the case. A variety of mechanisms ensure that this does not happen. Cellular needs and conditions vary from cell to cell, and change within individual cells over time. The required enzymes and energetic demands of stomach cells are different from those of fat storage cells, skin cells, blood cells, and nerve cells. Furthermore, a digestive cell works much harder to process and break down nutrients during the time that closely follows a meal compared with many hours after a meal. As these cellular demands and conditions vary, so do the amounts and functionality of different enzymes.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Ap biology - part 1: the cell' conversation and receive update notifications?