| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

It would seem ideal to have a scenario in which all of the enzymes encoded in an organism’s genome existed in abundant supply and functioned optimally under all cellular conditions, in all cells, at all times. In reality, this is far from the case. A variety of mechanisms ensure that this does not happen. Cellular needs and conditions vary from cell to cell, and change within individual cells over time. The required enzymes and energetic demands of stomach cells are different from those of fat storage cells, skin cells, blood cells, and nerve cells. Furthermore, a digestive cell works much harder to process and break down nutrients during the time that closely follows a meal compared with many hours after a meal. As these cellular demands and conditions vary, so do the amounts and functionality of different enzymes.

Since the rates of biochemical reactions are controlled by activation energy, and enzymes lower and determine activation energies for chemical reactions, the relative amounts and functioning of the variety of enzymes within a cell ultimately determine which reactions will proceed and at which rates. This determination is tightly controlled. In certain cellular environments, enzyme activity is partly controlled by environmental factors, like pH and temperature. There are other mechanisms through which cells control the activity of enzymes and determine the rates at which various biochemical reactions will occur.

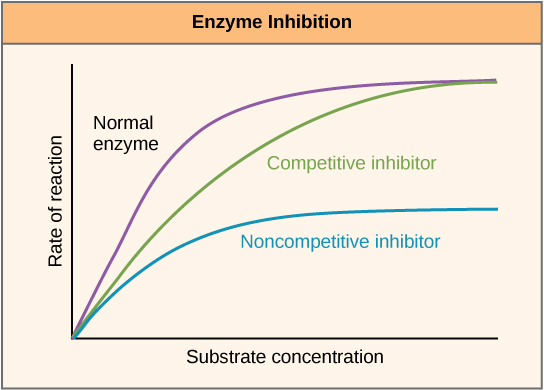

Enzymes can be regulated in ways that either promote or reduce their activity. There are many different kinds of molecules that inhibit or promote enzyme function, and various mechanisms exist for doing so. In some cases of enzyme inhibition, for example, an inhibitor molecule is similar enough to a substrate that it can bind to the active site and simply block the substrate from binding. When this happens, the enzyme is inhibited through competitive inhibition , because an inhibitor molecule competes with the substrate for active site binding ( [link] ). On the other hand, in noncompetitive inhibition, an inhibitor molecule binds to the enzyme in a location other than an allosteric site and still manages to block substrate binding to the active site.

Some inhibitor molecules bind to enzymes in a location where their binding induces a conformational change that reduces the affinity of the enzyme for its substrate. This type of inhibition is called allosteric inhibition ( [link] ). Most allosterically regulated enzymes are made up of more than one polypeptide, meaning that they have more than one protein subunit. When an allosteric inhibitor binds to an enzyme, all active sites on the protein subunits are changed slightly such that they bind their substrates with less efficiency. There are allosteric activators as well as inhibitors. Allosteric activators bind to locations on an enzyme away from the active site, inducing a conformational change that increases the affinity of the enzyme’s active site(s) for its substrate(s).

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Cell biology' conversation and receive update notifications?