| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

An increase in the price of some product signals consumers that there is a shortage and the product should perhaps be economized on. For example, if you are thinking about taking a plane trip to Hawaii, but the ticket turns out to be expensive during the week you intend to go, you might consider other weeks when the ticket might be cheaper. The price could be high because you were planning to travel during a holiday when demand for traveling is high. Or, maybe the cost of an input like jet fuel increased or the airline has raised the price temporarily to see how many people are willing to pay it. Perhaps all of these factors are present at the same time. You do not need to analyze the market and break down the price change into its underlying factors. You just have to look at the price of a ticket and decide whether and when to fly.

In the same way, price changes provide useful information to producers. Imagine the situation of a farmer who grows oats and learns that the price of oats has risen. The higher price could be due to an increase in demand caused by a new scientific study proclaiming that eating oats is especially healthful. Or perhaps the price of a substitute grain, like corn, has risen, and people have responded by buying more oats. But the oat farmer does not need to know the details. The farmer only needs to know that the price of oats has risen and that it will be profitable to expand production as a result.

The actions of individual consumers and producers as they react to prices overlap and interlock in markets for goods, labor, and financial capital. A change in any single market is transmitted through these multiple interconnections to other markets. The vision of the role of flexible prices helping markets to reach equilibrium and linking different markets together helps to explain why price controls can be so counterproductive. Price controls are government laws that serve to regulate prices rather than allow the various markets to determine prices. There is an old proverb: “Don’t kill the messenger.” In ancient times, messengers carried information between distant cities and kingdoms. When they brought bad news, there was an emotional impulse to kill the messenger. But killing the messenger did not kill the bad news. Moreover, killing the messenger had an undesirable side effect: Other messengers would refuse to bring news to that city or kingdom, depriving its citizens of vital information.

Those who seek price controls are trying to kill the messenger—or at least to stifle an unwelcome message that prices are bringing about the equilibrium level of price and quantity. But price controls do nothing to affect the underlying forces of demand and supply, and this can have serious repercussions. During China’s “Great Leap Forward” in the late 1950s, food prices were kept artificially low, with the result that 30 to 40 million people died of starvation because the low prices depressed farm production. Changes in demand and supply will continue to reveal themselves through consumers’ and producers’ behavior. Immobilizing the price messenger through price controls will deprive everyone in the economy of critical information. Without this information, it becomes difficult for everyone—buyers and sellers alike—to react in a flexible and appropriate manner as changes occur throughout the economy.

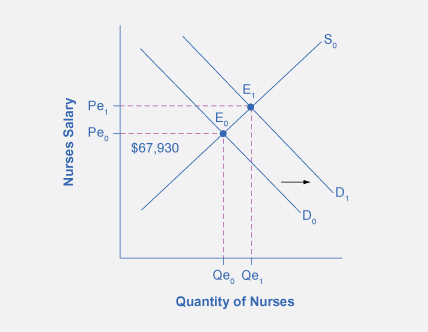

The theory of supply and demand can explain what happens in the labor markets and suggests that the demand for nurses will increase as healthcare needs of baby boomers increase, as [link] shows. The impact of that increase will result in an average salary higher than the $67,930 earned in 2012 referenced in the first part of this case. The new equilibrium (E 1 ) will be at the new equilibrium price (Pe 1 ).Equilibrium quantity will also increase from Qe 0 to Qe 1 .

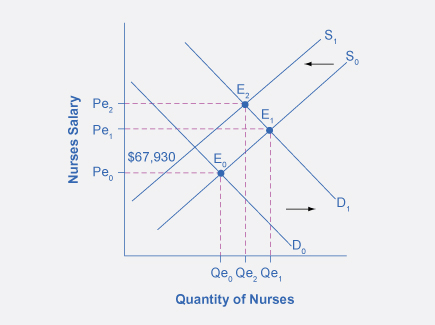

Suppose that as the demand for nurses increases, the supply shrinks due to an increasing number of nurses entering retirement and increases in the tuition of nursing degrees. The impact of a decreasing supply of nurses is captured by the leftward shift of the supply curve in [link] The shifts in the two curves result in higher salaries for nurses, but the overall impact in the quantity of nurses is uncertain, as it depends on the relative shifts of supply and demand.

While we do not know if the number of nurses will increase or decrease relative to their initial employment, we know they will have higher salaries. The situation of the labor market for nurses described in the beginning of the chapter is different from this example, because instead of a shrinking supply, we had the supply growing at a lower rate than the growth in demand. Since both curves were shifting to the right, we would have an unequivocal increase in the quantity of nurses. And because the shift in the demand curve was larger than the one in the supply, we would expect higher wages as a result.

The market price system provides a highly efficient mechanism for disseminating information about relative scarcities of goods, services, labor, and financial capital. Market participants do not need to know why prices have changed, only that the changes require them to revisit previous decisions they made about supply and demand. Price controls hide information about the true scarcity of products and thereby cause misallocation of resources.

Imagine that to preserve the traditional way of life in small fishing villages, a government decides to impose a price floor that will guarantee all fishermen a certain price for their catch.

What happens to the price and the quantity bought and sold in the cocoa market if countries producing cocoa experience a drought and a new study is released demonstrating the health benefits of cocoa? Illustrate your answer with a demand and supply graph.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Principles of economics' conversation and receive update notifications?