| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

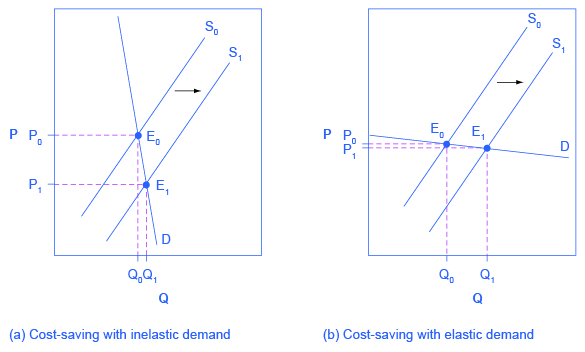

Producers of aspirin may find themselves in a nasty bind here. The situation shown in [link] , with extremely inelastic demand, means that a new invention may cause the price to drop dramatically while quantity changes little. As a result, the new production technology can lead to a drop in the revenue that firms earn from sales of aspirin. However, if strong competition exists between producers of aspirin, each producer may have little choice but to search for and implement any breakthrough that allows it to reduce production costs. After all, if one firm decides not to implement such a cost-saving technology, it can be driven out of business by other firms that do.

Since demand for food is generally inelastic, farmers may often face the situation in [link] (a). That is, a surge in production leads to a severe drop in price that can actually decrease the total revenue received by farmers. Conversely, poor weather or other conditions that cause a terrible year for farm production can sharply raise prices so that the total revenue received increases. The Clear It Up box discusses how these issues relate to coffee.

Coffee is an international crop. The top five coffee-exporting nations are Brazil, Vietnam, Colombia, Indonesia, and Ethiopia. In these nations and others, 20 million families depend on selling coffee beans as their main source of income. These families are exposed to enormous risk, because the world price of coffee bounces up and down. For example, in 1993, the world price of coffee was about 50 cents per pound; in 1995 it was four times as high, at $2 per pound. By 1997 it had fallen by half to $1.00 per pound. In 1998 it leaped back up to $2 per pound. By 2001 it had fallen back to 46 cents a pound; by early 2011 it went back up to about $2.31 per pound. By the end of 2012, the price had fallen back to about $1.31 per pound.

The reason for these price bounces lies in a combination of inelastic demand and shifts in supply. The elasticity of coffee demand is only about 0.3; that is, a 10% rise in the price of coffee leads to a decline of about 3% in the quantity of coffee consumed. When a major frost hit the Brazilian coffee crop in 1994, coffee supply shifted to the left with an inelastic demand curve, leading to much higher prices. Conversely, when Vietnam entered the world coffee market as a major producer in the late 1990s, the supply curve shifted out to the right. With a highly inelastic demand curve, coffee prices fell dramatically. This situation is shown in [link] (a).

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Openstax microeconomics in ten weeks' conversation and receive update notifications?