| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

In nature, some proteins are formed from several polypeptides, also known as subunits, and the interaction of these subunits forms the quaternary structure . Weak interactions between the subunits help to stabilize the overall structure. For example, insulin (a globular protein) has a combination of hydrogen bonds and disulfide bonds that cause it to be mostly clumped into a ball shape. Insulin starts out as a single polypeptide and loses some internal sequences in the presence of post-translational modification after the formation of the disulfide linkages that hold the remaining chains together. Silk (a fibrous protein), however, has a β -pleated sheet structure that is the result of hydrogen bonding between different chains.

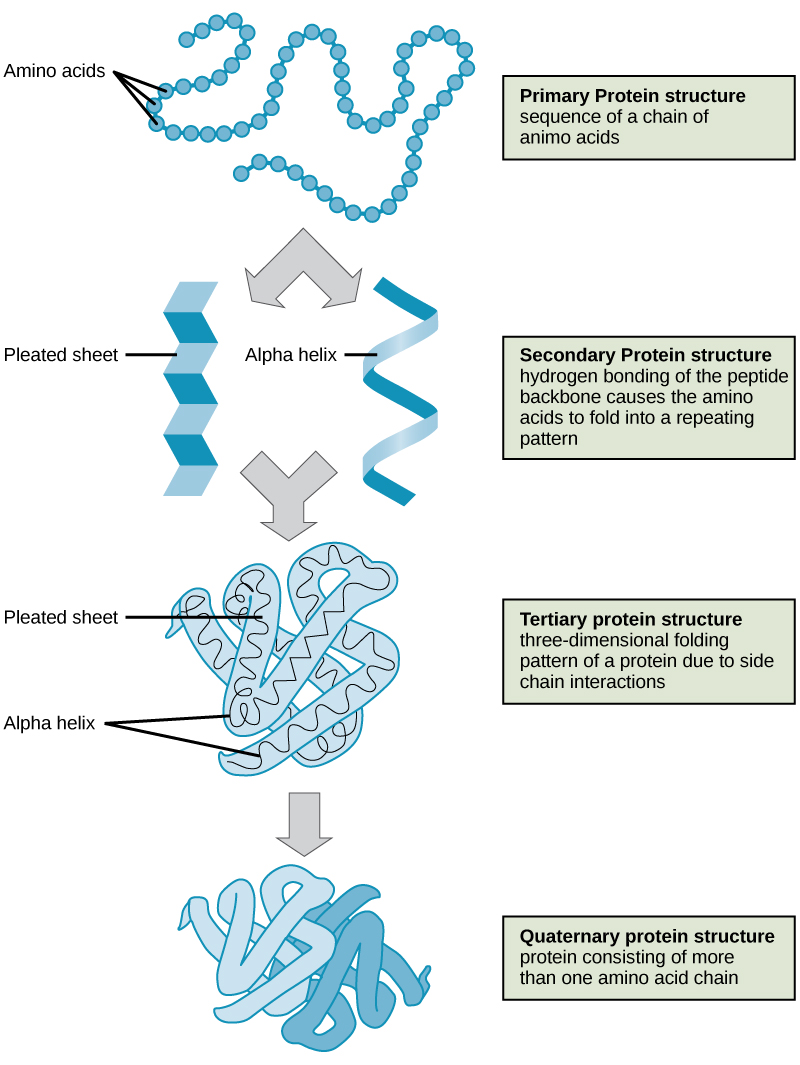

The four levels of protein structure (primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary) are illustrated in [link] .

Each protein has its own unique sequence and shape that are held together by chemical interactions. If the protein is subject to changes in temperature, pH, or exposure to chemicals, the protein structure may change, losing its shape without losing its primary sequence in what is known as denaturation . Denaturation is often reversible because the primary structure of the polypeptide is conserved in the process if the denaturing agent is removed, allowing the protein to resume its function. Sometimes denaturation is irreversible, leading to loss of function. One example of irreversible protein denaturation is when an egg is fried. The albumin protein in the liquid egg white is denatured when placed in a hot pan. "Too-high" temperature is relative; for instance, bacteria that survive in hot springs have proteins that function at temperatures close to boiling. The stomach is also very acidic (has a low pH), and denatures proteins as part of the digestion process; however, the digestive enzymes of the stomach retain their activity under these conditions.

Protein folding is critical to its function. It was originally thought that the proteins themselves were responsible for the folding process. Only recently was it found that often they receive assistance in the folding process from protein helpers known as chaperones (or chaperonins) that associate with the target protein during the folding process.

For an additional perspective on proteins, view this animation called “Biomolecules: The Proteins.”

Proteins are a class of macromolecules that perform a diverse range of functions for the cell. They help in metabolism by providing structural support and by acting as enzymes, carriers, or hormones. The building blocks of proteins (monomers) are amino acids. Each amino acid has a central carbon that is linked to an amino group, a carboxyl group, a hydrogen atom, and an R group or side chain. There are 20 commonly occurring amino acids, each of which differs in the R group. Each amino acid is linked to its neighbors by a peptide bond. A long chain of amino acids is known as a polypeptide.

Proteins are organized at four levels: primary, secondary, tertiary, and (optional) quaternary. The primary structure is the unique sequence of amino acids. The local folding of the polypeptide to form structures such as the α helix and β -pleated sheet constitutes the secondary structure. The overall three-dimensional structure is the tertiary structure. When two or more polypeptides combine to form the complete protein structure, the configuration is known as the quaternary structure of a protein. Protein shape and function are intricately linked; any change in shape caused by changes in temperature or pH may lead to protein denaturation and a loss in function.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'General biology part i - mixed majors' conversation and receive update notifications?