| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

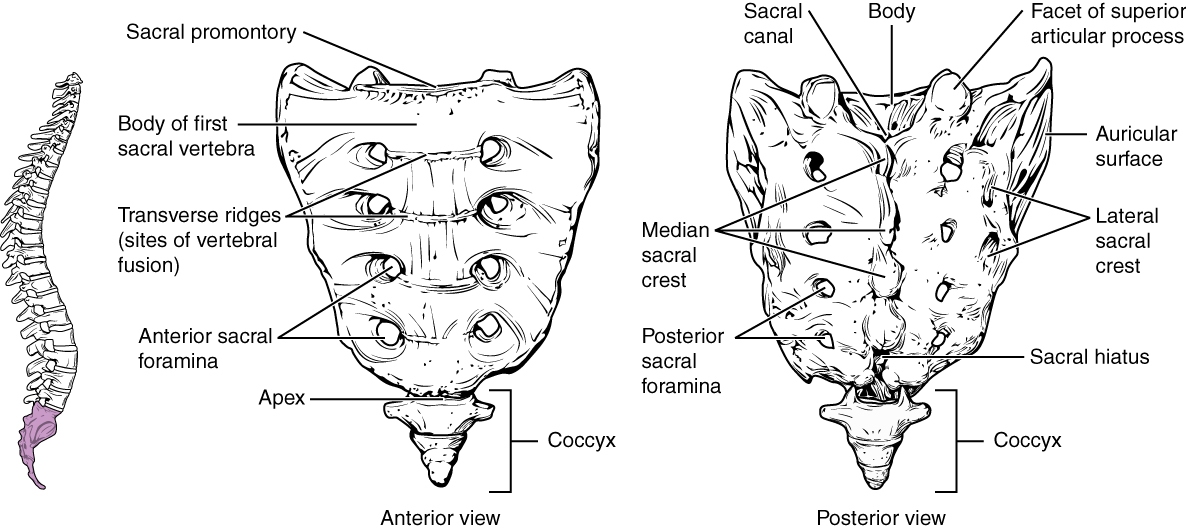

The sacral promontory is the anterior lip of the superior base of the sacrum. Lateral to this is the roughened auricular surface, which joins with the ilium portion of the hipbone to form the immobile sacroiliac joints of the pelvis. Passing inferiorly through the sacrum is a bony tunnel called the sacral canal , which terminates at the sacral hiatus near the inferior tip of the sacrum. The anterior and posterior surfaces of the sacrum have a series of paired openings called sacral foramina (singular = foramen) that connect to the sacral canal. Each of these openings is called a posterior (dorsal) sacral foramen or anterior (ventral) sacral foramen . These openings allow for the anterior and posterior branches of the sacral spinal nerves to exit the sacrum. The superior articular process of the sacrum , one of which is found on either side of the superior opening of the sacral canal, articulates with the inferior articular processes from the L5 vertebra.

The coccyx, or tailbone, is derived from the fusion of four very small coccygeal vertebrae (see [link] ). It articulates with the inferior tip of the sacrum. It is not weight bearing in the standing position, but may receive some body weight when sitting.

The bodies of adjacent vertebrae are strongly anchored to each other by an intervertebral disc. This structure provides padding between the bones during weight bearing, and because it can change shape, also allows for movement between the vertebrae. Although the total amount of movement available between any two adjacent vertebrae is small, when these movements are summed together along the entire length of the vertebral column, large body movements can be produced. Ligaments that extend along the length of the vertebral column also contribute to its overall support and stability.

An intervertebral disc is a fibrocartilaginous pad that fills the gap between adjacent vertebral bodies (see [link] ). Each disc is anchored to the bodies of its adjacent vertebrae, thus strongly uniting these. The discs also provide padding between vertebrae during weight bearing. Because of this, intervertebral discs are thin in the cervical region and thickest in the lumbar region, which carries the most body weight. In total, the intervertebral discs account for approximately 25 percent of your body height between the top of the pelvis and the base of the skull. Intervertebral discs are also flexible and can change shape to allow for movements of the vertebral column.

Each intervertebral disc consists of two parts. The anulus fibrosus is the tough, fibrous outer layer of the disc. It forms a circle (anulus = “ring” or “circle”) and is firmly anchored to the outer margins of the adjacent vertebral bodies. Inside is the nucleus pulposus , consisting of a softer, more gel-like material. It has a high water content that serves to resist compression and thus is important for weight bearing. With increasing age, the water content of the nucleus pulposus gradually declines. This causes the disc to become thinner, decreasing total body height somewhat, and reduces the flexibility and range of motion of the disc, making bending more difficult.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Anatomy & Physiology: support and movement' conversation and receive update notifications?