| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

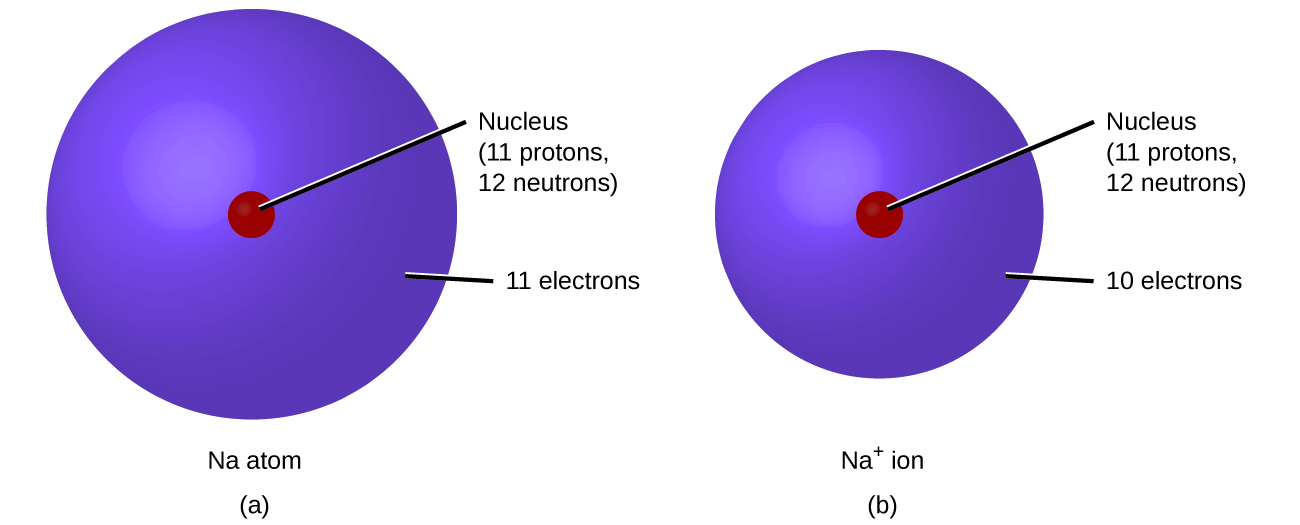

In ordinary chemical reactions, the nucleus of each atom (and thus the identity of the element) remains unchanged. Electrons, however, can be added to atoms by transfer from other atoms, lost by transfer to other atoms, or shared with other atoms. The transfer and sharing of electrons among atoms govern the chemistry of the elements. During the formation of some compounds, atoms gain or lose electrons, and form electrically charged particles called ions ( [link] ).

You can use the periodic table to predict whether an atom will form an anion or a cation, and you can often predict the charge of the resulting ion. Atoms of many main-group metals lose enough electrons to leave them with the same number of electrons as an atom of the preceding noble gas. To illustrate, an atom of an alkali metal (group 1) loses one electron and forms a cation with a 1+ charge; an alkaline earth metal (group 2) loses two electrons and forms a cation with a 2+ charge, and so on. For example, a neutral calcium atom, with 20 protons and 20 electrons, readily loses two electrons. This results in a cation with 20 protons, 18 electrons, and a 2+ charge. It has the same number of electrons as atoms of the preceding noble gas, argon, and is symbolized Ca 2+ . The name of a metal ion is the same as the name of the metal atom from which it forms, so Ca 2+ is called a calcium ion.

When atoms of nonmetal elements form ions, they generally gain enough electrons to give them the same number of electrons as an atom of the next noble gas in the periodic table. Atoms of group 17 gain one electron and form anions with a 1− charge; atoms of group 16 gain two electrons and form ions with a 2− charge, and so on. For example, the neutral bromine atom, with 35 protons and 35 electrons, can gain one electron to provide it with 36 electrons. This results in an anion with 35 protons, 36 electrons, and a 1− charge. It has the same number of electrons as atoms of the next noble gas, krypton, and is symbolized Br − . (A discussion of the theory supporting the favored status of noble gas electron numbers reflected in these predictive rules for ion formation is provided in a later chapter of this text.)

Note the usefulness of the periodic table in predicting likely ion formation and charge ( [link] ). Moving from the far left to the right on the periodic table, main-group elements tend to form cations with a charge equal to the group number. That is, group 1 elements form 1+ ions; group 2 elements form 2+ ions, and so on. Moving from the far right to the left on the periodic table, elements often form anions with a negative charge equal to the number of groups moved left from the noble gases. For example, group 17 elements (one group left of the noble gases) form 1− ions; group 16 elements (two groups left) form 2− ions, and so on. This trend can be used as a guide in many cases, but its predictive value decreases when moving toward the center of the periodic table. In fact, transition metals and some other metals often exhibit variable charges that are not predictable by their location in the table. For example, copper can form ions with a 1+ or 2+ charge, and iron can form ions with a 2+ or 3+ charge.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Ut austin - principles of chemistry' conversation and receive update notifications?