| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Cells are made of many complex molecules called macromolecules, such as proteins, nucleic acids (RNA and DNA), carbohydrates, and lipids. The macromolecules are a subset of organic molecules (any carbon-containing liquid, solid, or gas) that are especially important for life. The fundamental component for all of these macromolecules is carbon. The carbon atom has unique properties that allow it to form covalent bonds to as many as four different atoms, making this versatile element ideal to serve as the basic structural component, or “backbone,” of the macromolecules.

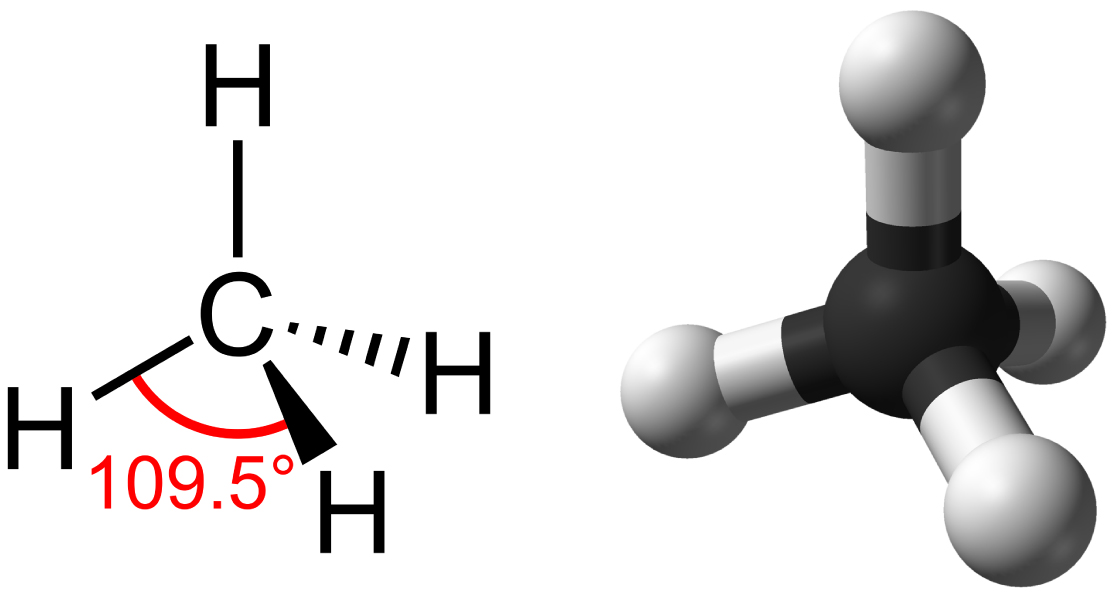

Individual carbon atoms have an incomplete outermost electron shell. With an atomic number of 6 (six electrons and six protons), the first two electrons fill the inner shell, leaving four in the second shell. Therefore, carbon atoms can form up to four covalent bonds with other atoms to satisfy the octet rule. The methane molecule provides an example: it has the chemical formula CH 4 . Each of its four hydrogen atoms forms a single covalent bond with the carbon atom by sharing a pair of electrons. This results in a filled outermost shell.

Hydrocarbons are organic molecules consisting entirely of carbon and hydrogen, such as methane (CH 4 ) described above. We often use hydrocarbons in our daily lives as fuels—like the propane in a gas grill or the butane in a lighter. The many covalent bonds between the atoms in hydrocarbons store a great amount of energy, which is released when these molecules are burned (oxidized). Methane, an excellent fuel, is the simplest hydrocarbon molecule, with a central carbon atom bonded to four different hydrogen atoms, as illustrated in [link] . The geometry of the methane molecule, where the atoms reside in three dimensions, is determined by the shape of its electron orbitals. The carbons and the four hydrogen atoms form a shape known as a tetrahedron, with four triangular faces; for this reason, methane is described as having tetrahedral geometry.

As the backbone of the large molecules of living things, hydrocarbons may exist as linear carbon chains, carbon rings, or combinations of both. Furthermore, individual carbon-to-carbon bonds may be single, double, or triple covalent bonds, and each type of bond affects the geometry of the molecule in a specific way. This three-dimensional shape or conformation of the large molecules of life (macromolecules) is critical to how they function.

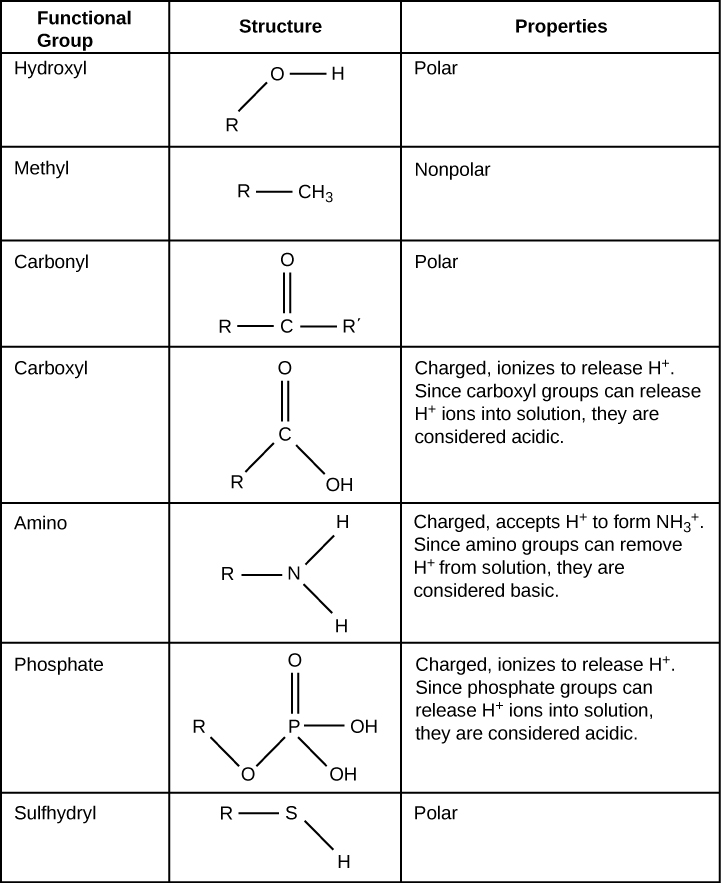

Functional groups are groups of atoms that occur within molecules and confer specific chemical properties to those molecules. They are found along the “carbon backbone” of macromolecules. This carbon backbone is formed by chains and/or rings of carbon atoms with the occasional substitution of an element such as nitrogen or oxygen. Molecules with other elements in their carbon backbone are substituted hydrocarbons .

The functional groups in a macromolecule are usually attached to the carbon backbone at one or several different places along its chain and/or ring structure. Each of the four types of macromolecules—proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids—has its own characteristic set of functional groups that contributes greatly to its differing chemical properties and its function in living organisms.

A functional group can participate in specific chemical reactions. Some of the important functional groups in biological molecules are shown in [link] ; they include: hydroxyl, methyl, carbonyl, carboxyl, amino, phosphate, and sulfhydryl. These groups play an important role in the formation of molecules like DNA, proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids. Functional groups are usually classified as hydrophobic or hydrophilic depending on their charge or polarity characteristics. An example of a hydrophobic group is the non-polar methane molecule. Among the hydrophilic functional groups is the carboxyl group found in amino acids, some amino acid side chains, and the fatty acids that form triglycerides and phospholipids. This carboxyl group ionizes to release hydrogen ions (H + ) from the COOH group resulting in the negatively charged COO - group; this contributes to the hydrophilic nature of whatever molecule it is found on. Other functional groups, such as the carbonyl group, have a partially negatively charged oxygen atom that may form hydrogen bonds with water molecules, again making the molecule more hydrophilic.

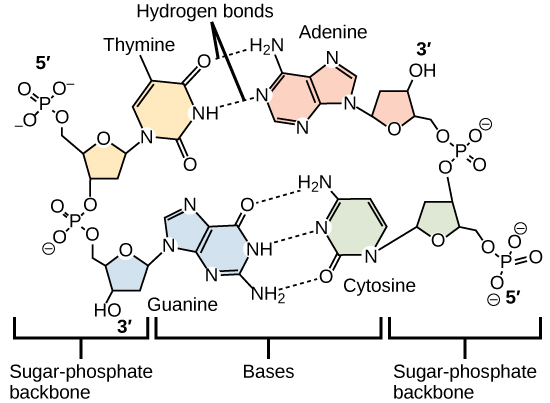

Hydrogen bonds between functional groups (within the same molecule or between different molecules) are important to the function of many macromolecules and help them to fold properly into and maintain the appropriate shape for functioning. Hydrogen bonds are also involved in various recognition processes, such as DNA complementary base pairing and the binding of an enzyme to its substrate, as illustrated in [link] .

The unique properties of carbon make it a central part of biological molecules. Carbon binds to oxygen, hydrogen, and nitrogen covalently to form the many molecules important for cellular function. Carbon has four electrons in its outermost shell and can form four bonds. Carbon and hydrogen can form hydrocarbon chains or rings. Functional groups are groups of atoms that confer specific properties to hydrocarbon (or substituted hydrocarbon) chains or rings that define their overall chemical characteristics and function.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'General biology part i - mixed majors' conversation and receive update notifications?