| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

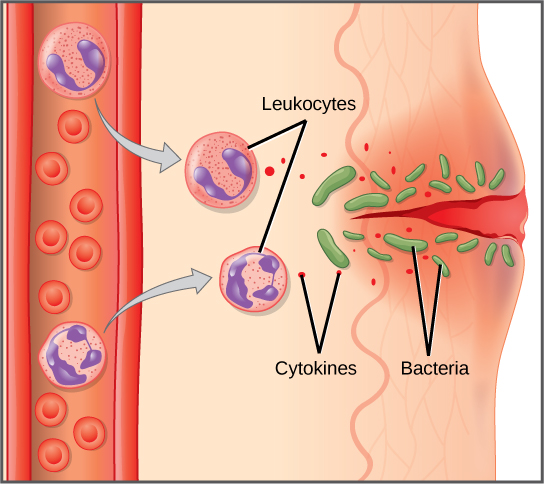

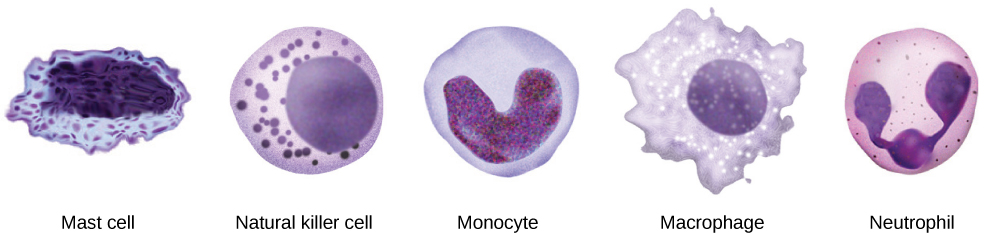

If pathogens defeat these defenses and enter the body, the innate immune system responds with a variety of internal defenses. These include the inflammatory response, phagocytosis, natural killer cells, and the complement system. White blood cells in the blood and lymph recognize pathogens as foreign to the body. A white blood cell is larger than a red blood cell, is nucleated, and is typically able to move using amoeboid locomotion. Because they can move on their own, white blood cells can leave the blood to go to infected tissues. For example, a monocyte is a type of white blood cell that circulates in the blood and lymph and develops into a macrophage after it moves into infected tissue. A macrophage is a large phagocytic cell that engulfs and devours foreign particles and pathogens.

Once a pathogen is recognized as foreign and devoured by a macrophage, chemicals called cytokines are released. A cytokine is a chemical messenger that regulates cell differentiation (form and function), proliferation (production), and gene expression to produce a variety of immune responses. Approximately 40 types of cytokines exist in humans. In addition to being released from white blood cells after pathogen recognition, cytokines are also released by the infected cells and bind to nearby uninfected cells, inducing those cells to release cytokines. This positive feedback loop results in a burst of cytokine production.

One class of early-acting cytokines is the interferons, which are released by infected cells as a warning to nearby uninfected cells. An interferon is a small protein that signals a viral infection to other cells. The interferons stimulate uninfected cells to produce compounds that interfere with viral replication. Interferons also activate macrophages and other cells.

The first cytokines to be produced encourage inflammation , a localized redness, swelling, heat, and pain. Inflammation is a response to physical trauma, such as a cut or a blow, chemical irritation, and infection by pathogens (viruses, bacteria, or fungi). The chemical signals that trigger an inflammatory response enter the extracellular fluid and cause capillaries to dilate (expand) and capillary walls to become more permeable, or leaky. The serum and other compounds leaking from capillaries cause swelling of the area, which in turn causes pain. Various kinds of white blood cells are attracted by the cytokines released at the area of inflammation. The types of white blood cells that arrive at an inflamed site depend on the nature of the injury or infecting pathogen. For example, a neutrophil is an early arriving white blood cell that engulfs and digests pathogens. Neutrophils are the most abundant white blood cells of the immune system ( [link] ). Macrophages follow neutrophils and take over the phagocytosis function and are involved in cleaning up cell debris and pathogens.

Cytokines also send feedback to cells of the nervous system to bring about the overall symptoms of feeling sick, which include lethargy, muscle pain, and nausea. Cytokines can thus increase the core body temperature, causing a fever. The elevated temperatures of a fever inhibit the growth of pathogens and speed up cellular repair processes. For these reasons, suppression of fevers should be limited to those that are dangerously high.

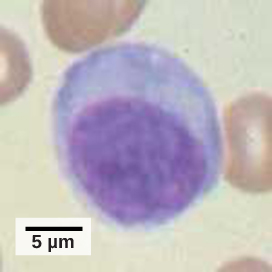

A lymphocyte is a white blood cell that contains a large nucleus ( [link] ). Most lymphocytes are associated with the adaptive immune response, but a class of lymphocytes known as natural killer cells are part of the innate immune system. Unlike other white blood cells that attack invading bacteria or fungi, natural killer (NK) cell is a lymphocyte kill body cells that infected with viruses (or cancerous cells). NK cells identify intracellular infections, especially from viruses, and attack the infected cells, destroying them so that they cannot release more viruses.

An array of approximately 20 types of proteins, called a complement system, is also activated by infection or the activity of the cells of the adaptive immune system and functions to destroy extracellular pathogens. Liver cells and macrophages synthesize inactive forms of complement proteins continuously; these proteins are abundant in the blood serum and are capable of responding immediately to infecting microorganisms. The complement system is so named because it is complementary to the innate and adaptive immune system. Complement proteins bind to the surfaces of microorganisms and are particularly attracted to pathogens that are already tagged by the adaptive immune system. This “tagging” involves the attachment of specific proteins called antibodies (discussed in detail later) to the pathogen. When they attach, the antibodies change shape providing a binding site for one of the complement proteins. After the first few complement proteins bind, a cascade of binding in a specific sequence of proteins follows in which the pathogen rapidly becomes coated in complement proteins.

Complement proteins perform several functions, one of which is to serve as a marker to indicate the presence of a pathogen to phagocytic cells and enhance engulfment. Certain complement proteins can combine to open pores in microbial cell membranes, causing ion leakage and lysis of the microbial cells.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Principles of biology' conversation and receive update notifications?