| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

The bryophytes are divided into three phyla: the liverworts or Hepaticophyta, the hornworts or Anthocerotophyta, and the mosses or true Bryophyta. The organisms in these three phyla share the following characteristics. Bryophytes lack vascular tissue, lack true leaves, lack seeds, use spores as a means of dispersal and have the gametophyte generation as the dominant (conspicuous) part of the life cycle. Even with all these characteristics in common, molecular and other evidence suggests that they do not form a single clade (a group that includes one common ancestor and all of its descendants)

Liverworts (Hepaticophyta) are viewed as the plants most closely related to the ancestor that moved to land. Liverworts have colonized every terrestrial habitat on Earth and diversified to more than 7,000 existing species ( [link] ). Some gametophytes form lobate green structures, as seen in [link] . The shape is similar to the lobes of the liver, and hence provides the origin of the name given to the phylum. Openings that allow the movement of gases may be observed in liverworts. However, these openings are not stomata, because they do not actively open and close. The plant takes up water over its entire surface and has no cuticle to prevent desiccation.

The lifecycle of a liverwort starts with the release of haploid spores from the sporangium that developed on the sporophyte. Spores disseminated by wind or water germinate into flattened thalli attached to the substrate by thin, single-celled filaments. Male and female gametangia develop on separate, individual plants. Once released, male gametes swim with the aid of their flagella to the female gametangium (the archegonium), and fertilization ensues. The zygote grows into a small sporophyte still attached to the parent gametophyte. It will give rise, by meiosis, to the next generation of spores. Liverwort plants can also reproduce asexually, by the breaking of branches or the spreading of leaf fragments called gemmae. In this latter type of reproduction, the gemmae—small, intact, complete pieces of plant that are produced in a cup on the surface of the thallus are splashed out of the cup by raindrops. The gemmae then land nearby and develop into gametophytes.

The hornworts ( Anthocerotophyta ) have colonized a variety of habitats on land, although they are never far from a source of moisture. The short, blue-green gametophyte is the dominant phase of the lifecycle of a hornwort. The narrow, pipe-like sporophyte is the defining characteristic of the group. The sporophytes emerge from the parent gametophyte and continue to grow throughout the life of the plant ( [link] ).

Stomata appear in the hornworts and are abundant on the sporophyte. Photosynthetic cells in the thallus contain a single chloroplast. Meristem cells at the base of the plant keep dividing and adding to its height. Many hornworts establish symbiotic relationships with cyanobacteria that fix nitrogen from the environment.

The lifecycle of hornworts follows the general pattern of alternation of generations. The gametophytes grow as flat thalli on the soil with embedded gametangia. Flagellated sperm swim to the archegonia and fertilize eggs. The zygote develops into a long and slender sporophyte that eventually splits open, releasing spores. The haploid spores germinate and give rise to the next generation of gametophyte.

More than 10,000 species of mosses have been catalogued. Their habitats vary from the tundra, where they are the main vegetation, to the understory of tropical forests. In the tundra, the mosses’ shallow rhizoids allow them to fasten to a substrate without penetrating the frozen soil. Mosses slow down erosion, store moisture and soil nutrients, and provide shelter for small animals as well as food for larger herbivores, such as the musk ox. Mosses are very sensitive to air pollution and are used to monitor air quality. They are also sensitive to copper salts, so these salts are a common ingredient of compounds marketed to eliminate mosses from lawns.

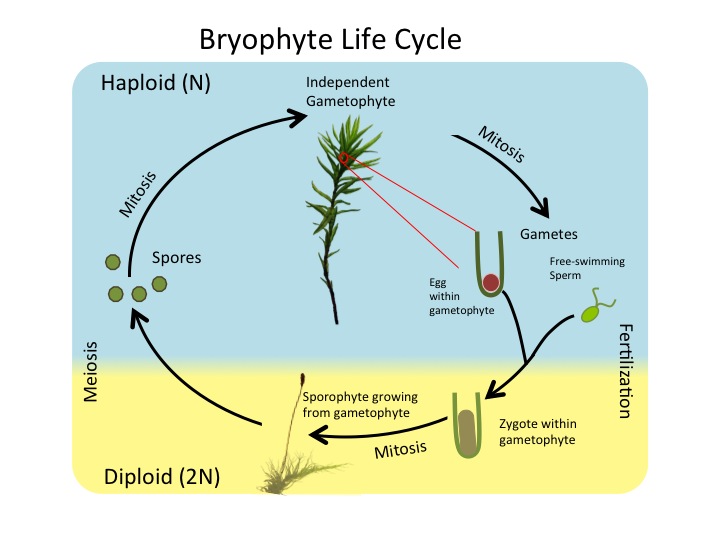

Mosses form diminutive gametophytes, which are the dominant phase of the lifecycle. Green, flat structures—resembling true leaves, but lacking vascular tissue—are attached in a spiral to a central stalk. The plants absorb water and nutrients directly through these leaf-like structures. Some mosses have small branches. Some primitive traits of green algae, such as flagellated sperm, are still present in mosses that are dependent on water for reproduction. Other features of mosses are clearly adaptations to dry land. For example, stomata are present on the stems of the sporophyte, and a primitive vascular system runs up the sporophyte’s stalk. Additionally, mosses are anchored to the substrate—whether it is soil, rock, or roof tiles—by multicellular rhizoids. These structures are precursors of roots. They originate from the base of the gametophyte, but are not the major route for the absorption of water and minerals. The lack of a true root system explains why it is so easy to rip moss mats from a tree trunk. The moss lifecycle follows the pattern of alternation of generations as shown in [link] .

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Principles of biology' conversation and receive update notifications?