| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

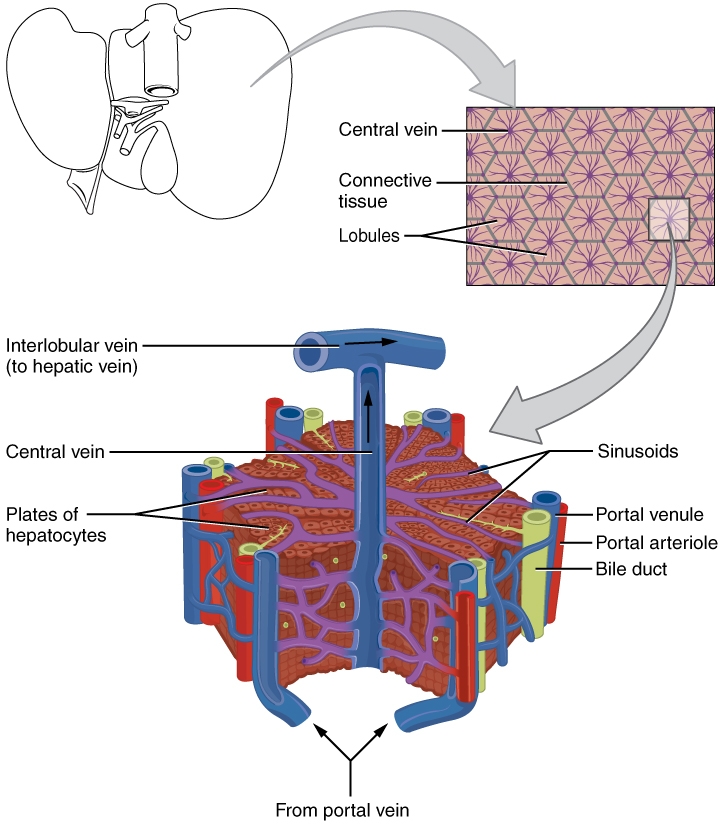

The liver has three main components: hepatocytes, bile canaliculi, and hepatic sinusoids. A hepatocyte is the liver’s main cell type, accounting for around 80 percent of the liver's volume. These cells play a role in a wide variety of secretory, metabolic, and endocrine functions. Plates of hepatocytes called hepatic laminae radiate outward from the portal vein in each hepatic lobule .

Between adjacent hepatocytes, grooves in the cell membranes provide room for each bile canaliculus (plural = canaliculi). These small ducts accumulate the bile produced by hepatocytes. From here, bile flows first into bile ductules and then into bile ducts. The bile ducts unite to form the larger right and left hepatic ducts, which themselves merge and exit the liver as the common hepatic duct . This duct then joins with the cystic duct from the gallbladder, forming the common bile duct through which bile flows into the small intestine.

A hepatic sinusoid is an open, porous blood space formed by fenestrated capillaries from nutrient-rich hepatic portal veins and oxygen-rich hepatic arteries. Hepatocytes are tightly packed around the fenestrated endothelium of these spaces, giving them easy access to the blood. From their central position, hepatocytes process the nutrients, toxins, and waste materials carried by the blood. Materials such as bilirubin are processed and excreted into the bile canaliculi. Other materials including proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates are processed and secreted into the sinusoids or just stored in the cells until called upon. The hepatic sinusoids combine and send blood to a central vein . Blood then flows through a hepatic vein into the inferior vena cava. This means that blood and bile flow in opposite directions. The hepatic sinusoids also contain star-shaped reticuloendothelial cells (Kupffer cells), phagocytes that remove dead red and white blood cells, bacteria, and other foreign material that enter the sinusoids. The portal triad is a distinctive arrangement around the perimeter of hepatic lobules, consisting of three basic structures: a bile duct, a hepatic artery branch, and a hepatic portal vein branch.

Recall that lipids are hydrophobic, that is, they do not dissolve in water. Thus, before they can be digested in the watery environment of the small intestine, large lipid globules must be broken down into smaller lipid globules, a process called emulsification. Bile is a mixture secreted by the liver to accomplish the emulsification of lipids in the small intestine.

Hepatocytes secrete about one liter of bile each day. A yellow-brown or yellow-green alkaline solution (pH 7.6 to 8.6), bile is a mixture of water, bile salts, bile pigments, phospholipids (such as lecithin), electrolytes, cholesterol, and triglycerides. The components most critical to emulsification are bile salts and phospholipids, which have a nonpolar (hydrophobic) region as well as a polar (hydrophilic) region. The hydrophobic region interacts with the large lipid molecules, whereas the hydrophilic region interacts with the watery chyme in the intestine. This results in the large lipid globules being pulled apart into many tiny lipid fragments of about 1 µ m in diameter. This change dramatically increases the surface area available for lipid-digesting enzyme activity. This is the same way dish soap works on fats mixed with water.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Anatomy & Physiology: energy, maintenance and environmental exchange' conversation and receive update notifications?