| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

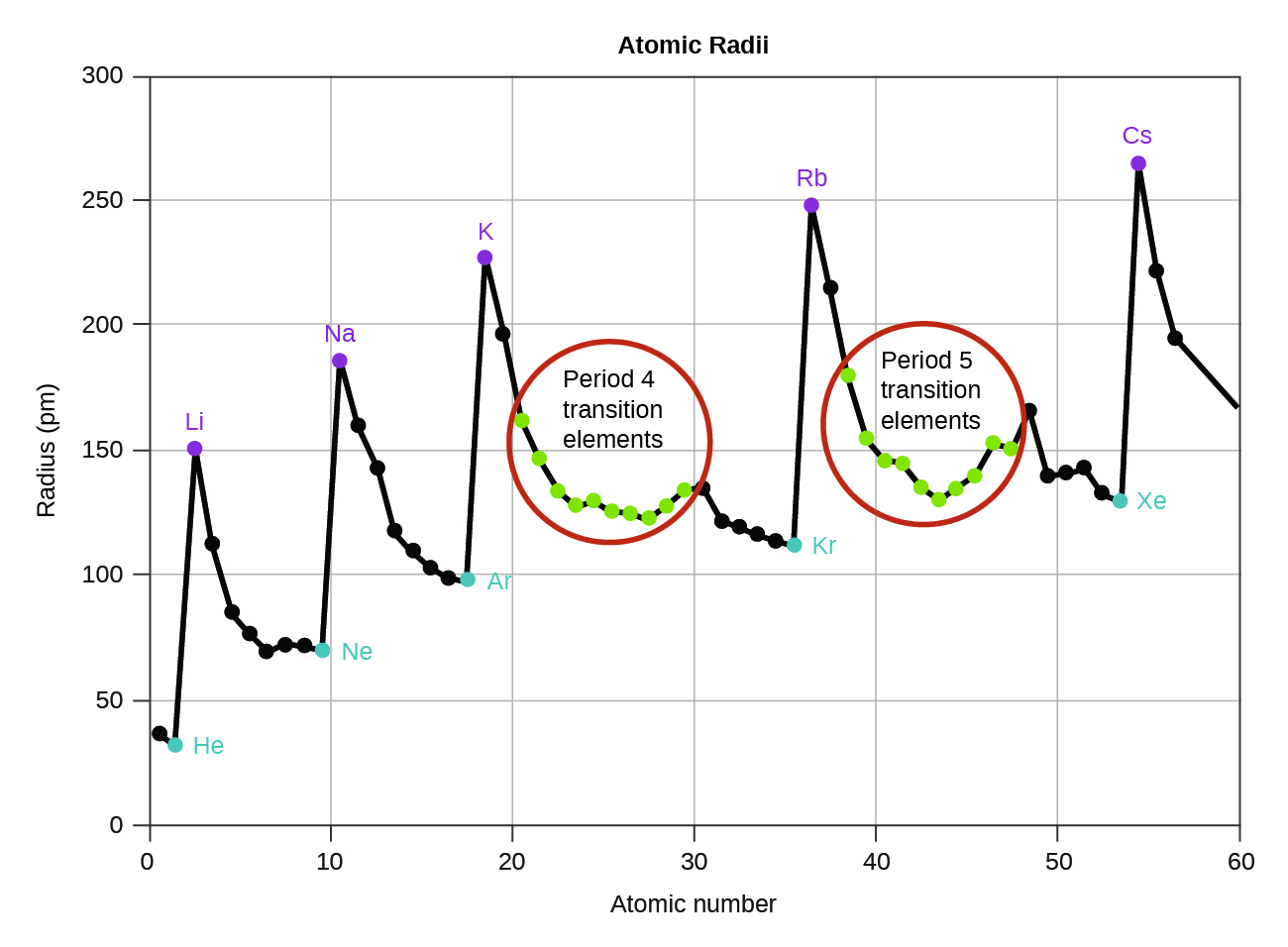

As shown in [link] , as we move across a period from left to right, we generally find that each element has a smaller covalent radius than the element preceding it. This might seem counterintuitive because it implies that atoms with more electrons have a smaller atomic radius. This can be explained with the concept of effective nuclear charge, Z eff . This is the pull exerted on a specific electron by the nucleus, taking into account any electron–electron repulsions. For hydrogen, there is only one electron and so the nuclear charge ( Z ) and the effective nuclear charge ( Z eff ) are equal. For all other atoms, the inner electrons partially shield the outer electrons from the pull of the nucleus, and thus:

Shielding is determined by the probability of another electron being between the electron of interest and the nucleus, as well as by the electron–electron repulsions the electron of interest encounters. Core electrons are adept at shielding, while electrons in the same valence shell do not block the nuclear attraction experienced by each other as efficiently. Thus, each time we move from one element to the next across a period, Z increases by one, but the shielding increases only slightly. Thus, Z eff increases as we move from left to right across a period. The stronger pull (higher effective nuclear charge) experienced by electrons on the right side of the periodic table draws them closer to the nucleus, making the covalent radii smaller.

Thus, as we would expect, the outermost or valence electrons are easiest to remove because they have the highest energies, are shielded more, and are farthest from the nucleus. As a general rule, when the representative elements form cations, they do so by the loss of the ns or np electrons that were added last in the Aufbau process. The transition elements, on the other hand, lose the ns electrons before they begin to lose the ( n – 1) d electrons, even though the ns electrons are added first, according to the Aufbau principle.

Ne or He

Ionic radius is the measure used to describe the size of an ion. A cation always has fewer electrons and the same number of protons as the parent atom; it is smaller than the atom from which it is derived ( [link] ). For example, the covalent radius of an aluminum atom (1 s 2 2 s 2 2 p 6 3 s 2 3 p 1 ) is 118 pm, whereas the ionic radius of an Al 3+ (1 s 2 2 s 2 2 p 6 ) is 68 pm. As electrons are removed from the outer valence shell, the remaining core electrons occupying smaller shells experience a greater effective nuclear charge Z eff (as discussed) and are drawn even closer to the nucleus.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Ut austin - principles of chemistry' conversation and receive update notifications?