| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

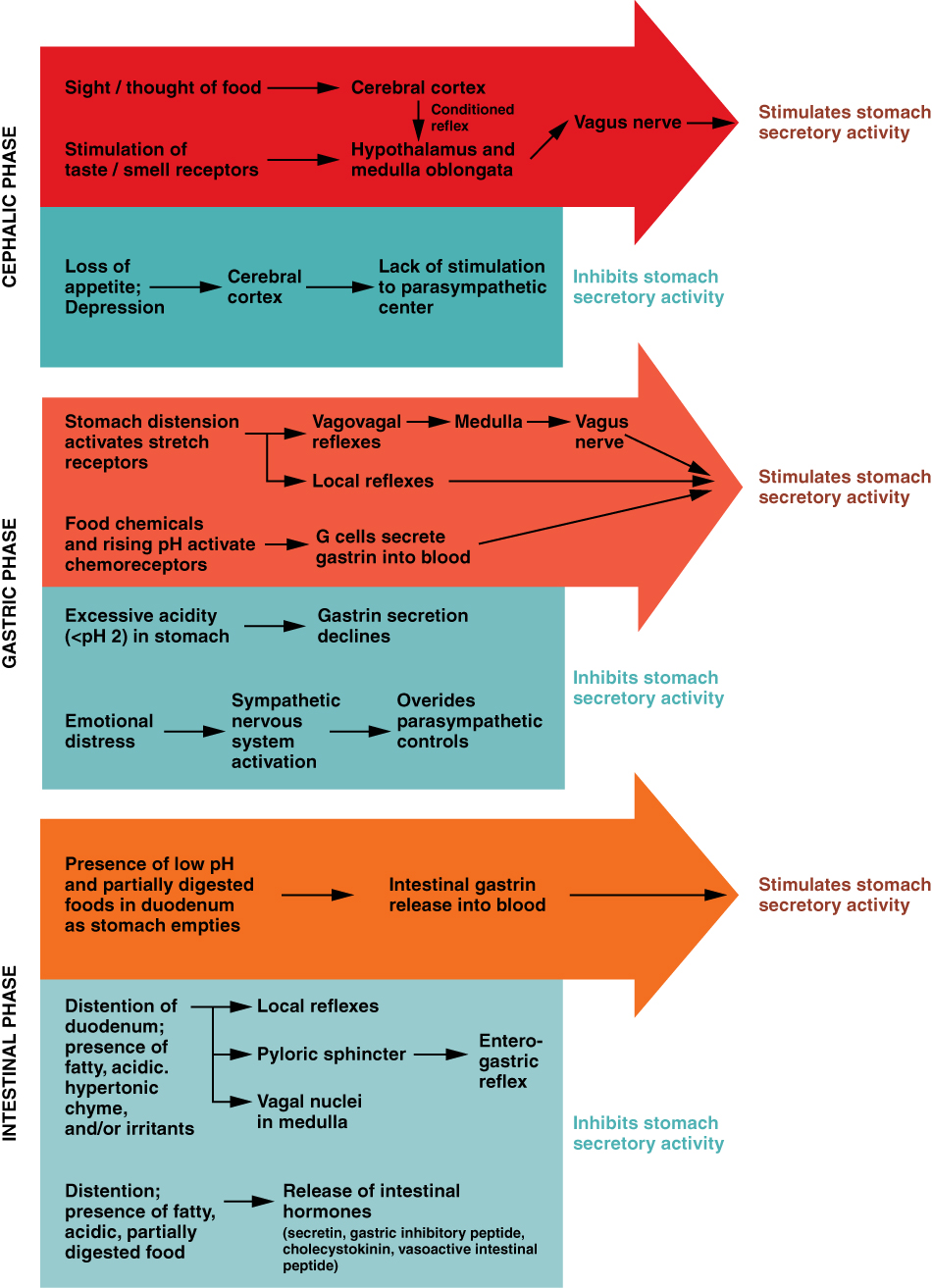

The cephalic phase (reflex phase) of gastric secretion, which is relatively brief, takes place before food enters the stomach. The smell, taste, sight, or thought of food triggers this phase. For example, when you bring a piece of sushi to your lips, impulses from receptors in your taste buds or the nose are relayed to your brain, which returns signals that increase gastric secretion to prepare your stomach for digestion. This enhanced secretion is a conditioned reflex, meaning it occurs only if you like or want a particular food. Depression and loss of appetite can suppress the cephalic reflex.

The gastric phase of secretion lasts 3 to 4 hours, and is set in motion by local neural and hormonal mechanisms triggered by the entry of food into the stomach. For example, when your sushi reaches the stomach, it creates distention that activates the stretch receptors. This stimulates parasympathetic neurons to release acetylcholine, which then provokes increased secretion of gastric juice. Partially digested proteins, caffeine, and rising pH stimulate the release of gastrin from enteroendocrine G cells, which in turn induces parietal cells to increase their production of HCl, which is needed to create an acidic environment for the conversion of pepsinogen to pepsin, and protein digestion. Additionally, the release of gastrin activates vigorous smooth muscle contractions. However, it should be noted that the stomach does have a natural means of avoiding excessive acid secretion and potential heartburn. Whenever pH levels drop too low, cells in the stomach react by suspending HCl secretion and increasing mucous secretions.

The intestinal phase of gastric secretion has both excitatory and inhibitory elements. The duodenum has a major role in regulating the stomach and its emptying. When partially digested food fills the duodenum, intestinal mucosal cells release a hormone called intestinal (enteric) gastrin, which further excites gastric juice secretion. This stimulatory activity is brief, however, because when the intestine distends with chyme, the enterogastric reflex inhibits secretion. One of the effects of this reflex is to close the pyloric sphincter, which blocks additional chyme from entering the duodenum.

The mucosa of the stomach is exposed to the highly corrosive acidity of gastric juice. Gastric enzymes that can digest protein can also digest the stomach itself. The stomach is protected from self-digestion by the mucosal barrier . This barrier has several components. First, the stomach wall is covered by a thick coating of bicarbonate-rich mucus. This mucus forms a physical barrier, and its bicarbonate ions neutralize acid. Second, the epithelial cells of the stomach's mucosa meet at tight junctions, which block gastric juice from penetrating the underlying tissue layers. Finally, stem cells located where gastric glands join the gastric pits quickly replace damaged epithelial mucosal cells, when the epithelial cells are shed. In fact, the surface epithelium of the stomach is completely replaced every 3 to 6 days.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Anatomy & Physiology: energy, maintenance and environmental exchange' conversation and receive update notifications?