| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

We know that a supply curve shows the minimum price a firm will accept to produce a given quantity of output. What happens to the supply curve when the cost of production goes up? Following is an example of a shift in supply due to a production cost increase.

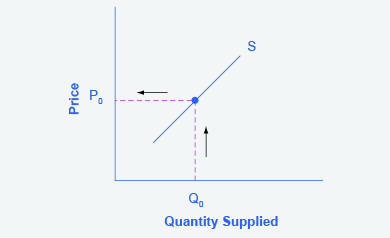

Step 1. Draw a graph of a supply curve for pizza. Pick a quantity (like Q 0 ). If you draw a vertical line up from Q 0 to the supply curve, you will see the price the firm chooses. An example is shown in [link] .

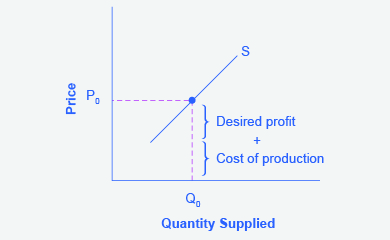

Step 2. Why did the firm choose that price and not some other? One way to think about this is that the price is composed of two parts. The first part is the average cost of production, in this case, the cost of the pizza ingredients (dough, sauce, cheese, pepperoni, and so on), the cost of the pizza oven, the rent on the shop, and the wages of the workers. The second part is the firm’s desired profit, which is determined, among other factors, by the profit margins in that particular business. If you add these two parts together, you get the price the firm wishes to charge. The quantity Q0 and associated price P0 give you one point on the firm’s supply curve, as shown in [link] .

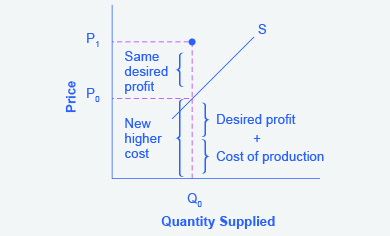

Step 3. Now, suppose that the cost of production goes up. Perhaps cheese has become more expensive by $0.75 per pizza. If that is true, the firm will want to raise its price by the amount of the increase in cost ($0.75). Draw this point on the supply curve directly above the initial point on the curve, but $0.75 higher, as shown in [link] .

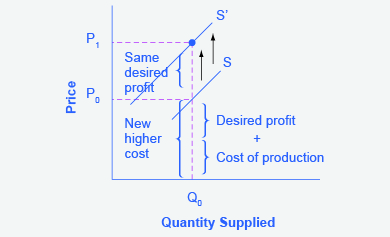

Step 4. Shift the supply curve through this point. You will see that an increase in cost causes an upward (or a leftward) shift of the supply curve so that at any price, the quantities supplied will be smaller, as shown in [link] .

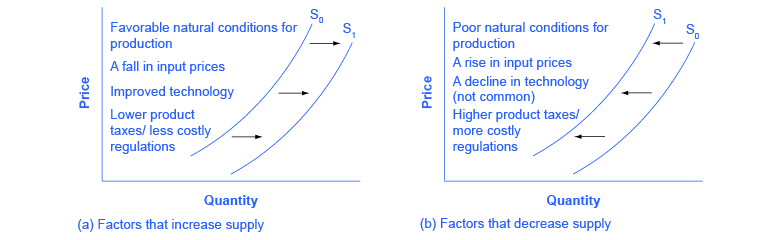

Changes in the cost of inputs, natural disasters, new technologies, and the impact of government decisions all affect the cost of production. In turn, these factors affect how much firms are willing to supply at any given price.

[link] summarizes factors that change the supply of goods and services. Notice that a change in the price of the product itself is not among the factors that shift the supply curve. Although a change in price of a good or service typically causes a change in quantity supplied or a movement along the supply curve for that specific good or service, it does not cause the supply curve itself to shift.

Because demand and supply curves appear on a two-dimensional diagram with only price and quantity on the axes, an unwary visitor to the land of economics might be fooled into believing that economics is about only four topics: demand, supply, price, and quantity. However, demand and supply are really “umbrella” concepts: demand covers all the factors that affect demand, and supply covers all the factors that affect supply. Factors other than price that affect demand and supply are included by using shifts in the demand or the supply curve. In this way, the two-dimensional demand and supply model becomes a powerful tool for analyzing a wide range of economic circumstances.

Economists often use the ceteris paribus or “other things being equal” assumption: while examining the economic impact of one event, all other factors remain unchanged for the purpose of the analysis. Factors that can shift the demand curve for goods and services, causing a different quantity to be demanded at any given price, include changes in tastes, population, income, prices of substitute or complement goods, and expectations about future conditions and prices. Factors that can shift the supply curve for goods and services, causing a different quantity to be supplied at any given price, include input prices, natural conditions, changes in technology, and government taxes, regulations, or subsidies.

[link] shows information on the demand and supply for bicycles, where the quantities of bicycles are measured in thousands.

| Price | Qd | Qs |

|---|---|---|

| $120 | 50 | 36 |

| $150 | 40 | 40 |

| $180 | 32 | 48 |

| $210 | 28 | 56 |

| $240 | 24 | 70 |

The computer market in recent years has seen many more computers sell at much lower prices. What shift in demand or supply is most likely to explain this outcome? Sketch a demand and supply diagram and explain your reasoning for each.

Landsburg, Steven E. The Armchair Economist: Economics and Everyday Life . New York: The Free Press. 2012. specifically Section IV: How Markets Work.

National Chicken Council. 2015. "Per Capita Consumption of Poultry and Livestock, 1965 to Estimated 2015, in Pounds." Accessed April 13, 2015. http://www.nationalchickencouncil.org/about-the-industry/statistics/per-capita-consumption-of-poultry-and-livestock-1965-to-estimated-2012-in-pounds/.

Wessel, David. “Saudi Arabia Fears $40-a-Barrel Oil, Too.” The Wall Street Journal . May 27, 2004, p. 42. http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB108561000087822300.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Openstax microeconomics in ten weeks' conversation and receive update notifications?