| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Map of the american hemisphere, 1823

Similar to other works of the time, Dunham foregrounds the exoticism of the foreign that readers found so tantalizing. Arriving in Brazil for the first time, he marvels at the sense of difference he feels between this place and the U.S.: “I first sett (sic) foot on land in Bahia in Brazill (sic) and looked around in astonishment it seemed like being transported to another planet more than being on this continent everything was new and wonderfull (sic) the buildings without any chimneys and covered with tiles the streets narrow and full of negroes a jabbering” (35). He goes on to write, in a similar vein, “the trees green and covered with tropical fruit and every thing else so different from home that was some time before I could realize that I was here” (36). The combination of foreign landscape, architecture, and peoples overwhelms Dunham, producing in him a sense of disorientation that was common among nineteenth-century author-travelers. At the same time, the presence of a black slave population would have been a point of keen interest, as well as identification, for many U.S. readers. Dunham no doubt knew that readers would be projecting their own experiences with slavery onto these moments within his journal, exciting curiosity about his experiences and debate about the relative merits and practices of the slave system. Many critics, such as Amy Kaplan in The Anarchy of Empire in the Making of U.S. Culture , have written that it is this blurring of the domestic and the foreign, of home and abroad, that is central to the socio-cultural operations of travel literature.

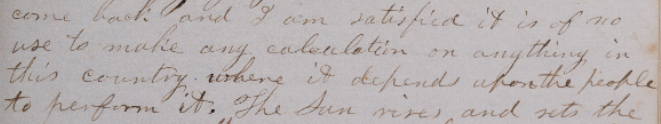

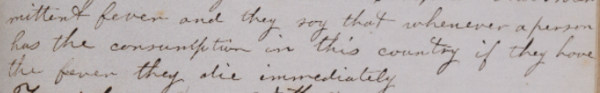

Later in the journal, after he has spent some time in Brazil, Dunham engages in sharp criticisms of the practical workings of this society, another familiar trope from the travel narrative. Manifestations of his frustration take on nationalist overtones in statements such as, “I am satisfied it is of no use to make any calculation on anything in this country where it depends upon the people to perform it” (see Figure 2 [a]); or, “they say that whenever a person has the consumption in this country if they have the fever they die immediately” (see Figure 2 [b]). The latter pronouncement portends the death of the American traveler owing to the relative medical backwardness of foreign lands. The implied superiority of U.S. knowledges and practices pervades much travel literature of this time, including those aforementioned texts concerning the burgeoning western frontier. As scholars have noted, these articulated attitudes toward the western territories invited, or perhaps even demanded, the civilizing influence emblematized by competent white Americans.

A journey to brazil, 1853

Page 135

Page 221

In designing a lesson plan around Journey to Brazil and nineteenth-century U.S. travel narratives, an instructor may also want to include a representative of those works dedicated to travel in the Holy Land. Texts that focused on journeys to Palestine and its surrounding territories enjoyed a massive degree of popularity among American readers, particularly in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Some of the more popular of these works included Twain’s The Innocents Abroad (1869) and W. M. Thomson’s The Land and the Book (1870), an illustrated travelogue of the Holy Land. In his critical study American Palestine: Melville, Twain, and the Holy Land Mania , Hilton Obenzinger argues that since many Americans regarded themselves as a chosen people, anointed by God to carry out a revivalist mission in this new nation, written works on the Holy Land held for them a special interest. Obenzinger insists, and many critics agree with him, that even if Holy Land literature was not the most popular form of travel narrative (though it may have been), then it was certainly the most ideologically significant. Dunham’s journal forces us to at least re-think that assertion. The 1853 publication of the journal shows an interest on the part of the American reading public in travel, both real and imagined, to places throughout the Americas as well. Richard Henry Dana, the same man who famously wrote on the western frontier, would chronicle his travels in the Caribbean in an 1859 book entitled To Cuba and Back: A Vacation Voyage . John O’Sullivan, accredited with the coining of the term “Manifest Destiny,” would in later years become a staunch advocate for the annexation of Cuba to the U.S. Finally, A Journey to Brazil provides yet another piece of compelling evidence that the hemisphere as a whole played a role in the U.S. imagination equal to that of both the western frontier and the Holy Land.

Bibliography

Dana, Richard Henry. Two Years Before the Mast and Other Voyages . New York: Library of America, 2005.

Edwards, Justin. Exotic Journeys: Exploring the Erotics of U.S. Travel Literature, 1849-1930 . Hanover, NH: UP of New England, 2001.

Kaplan, Amy. The Anarchy of Empire in the Making of U.S. Culture . Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2002.

Obenzinger, Hilton. American Palestine: Melville, Twain, and the Holy Land Mania . Princeton: Princeton UP, 1999.

Thomson, W. M. The Land and the Book . London: T. Nelson and Sons, 1870.

Twain, Mark. The Innocents Abroad; Roughing It . New York: Library of America, 1984.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Permalink testing' conversation and receive update notifications?