| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

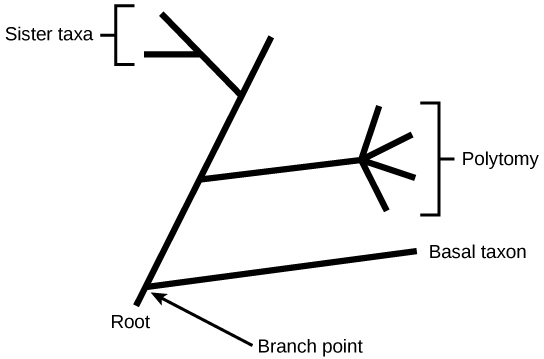

The diagrams above can serve as a pathway to understanding evolutionary history. The pathway can be traced from the origin of life to any individual species by navigating through the evolutionary branches between the two points. Also, by starting with a single species and tracing back towards the "trunk" of the tree, one can discover that species' ancestors, as well as where lineages share a common ancestry. In addition, the tree can be used to study entire groups of organisms.

Another point to mention on phylogenetic tree structure is that rotation at branch points does not change the information. For example, if a branch point was rotated and the taxon order changed, this would not alter the information because the evolution of each taxon from the branch point was independent of the other.

Many disciplines within the study of biology contribute to understanding how past and present life evolved over time; these disciplines together contribute to building, updating, and maintaining the “tree of life.” Information is used to organize and classify organisms based on evolutionary relationships in a scientific field called systematics . Data may be collected from fossils, from studying the structure of body parts or molecules used by an organism, and by DNA analysis. By combining data from many sources, scientists can put together the phylogeny of an organism; since phylogenetic trees are hypotheses, they will continue to change as new types of life are discovered and new information is learned.

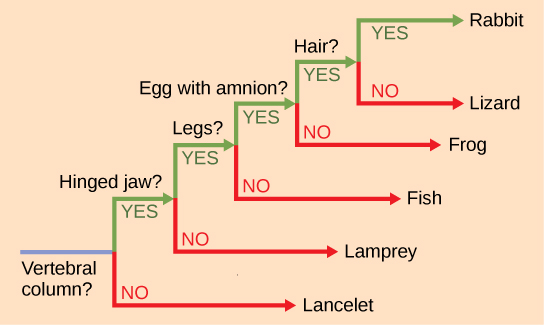

It may be easy to assume that more closely related organisms look more alike, and while this is often the case, it is not always true. If two closely related lineages evolved under significantly varied surroundings or after the evolution of a major new adaptation, it is possible for the two groups to appear more different than other groups that are not as closely related. For example, the phylogenetic tree in [link] shows that lizards and rabbits both have amniotic eggs, whereas frogs do not; yet lizards and frogs appear more similar than lizards and rabbits.

Another aspect of phylogenetic trees is that, unless otherwise indicated, the branches do not account for length of time, only the evolutionary order. In other words, the length of a branch does not typically mean more time passed, nor does a short branch mean less time passed— unless specified on the diagram. For example, in [link] , the tree does not indicate how much time passed between the evolution of amniotic eggs and hair. What the tree does show is the order in which things took place. Again using [link] , the tree shows that the oldest trait is the vertebral column, followed by hinged jaws, and so forth. Remember that any phylogenetic tree is a part of the greater whole, and like a real tree, it does not grow in only one direction after a new branch develops. So, for the organisms in [link] , just because a vertebral column evolved does not mean that invertebrate evolution ceased, it only means that a new branch formed. Also, groups that are not closely related, but evolve under similar conditions, may appear more phenotypically similar to each other than to a close relative.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'General biology i lecture' conversation and receive update notifications?