| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

In contrast to the functionalist approach, theoretical models in the conflict perspective focus on the way that urban areas change according to specific decisions made by political and economic leaders. These decisions generally benefit the middle and upper classes while exploiting the working and lower classes.

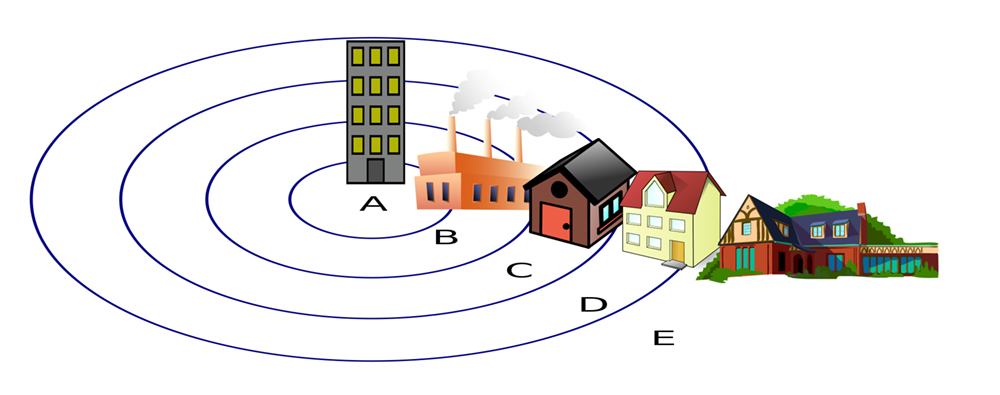

For example, sociologists Feagin and Parker (1990) suggested three aspects to understanding how political and economic leaders control urban growth. First, economic and political leaders work alongside each other to affect change in urban growth and decline, determining where money flows and how land use is regulated. Second, exchange value and use value are balanced to favor the middle and upper classes so that, for example, public land in poor neighborhoods may be rezoned for use as industrial land. Finally, urban development is dependent on both structure (groups such as local government) and agency (individuals including businessmen and activists), and these groups engage in a push-pull dynamic that determines where and how land is actually used. For example, NIMBY (Not In My Backyard) movements are more likely to emerge in middle and upper-class neighborhoods, so these groups have more control over the usage of local land.

For some women, caring for their children is a part of everyday life. For others, caring for other people’s children is a job, and often it is a job that takes them away from their own families and increasingly, their own countries. Feminist sociologists (a branch of the conflict theory perspective) find topics like these rich sources of research for the discipline.

A 2001 article by sociologist Arlie Hochschild in American Prospect magazine discusses the global phenomenon of women leaving their own families behind in developing countries in order to come to America to be a nanny for wealthy U.S. families. These women’s own children, left behind, might be looked after by an older sibling, a spouse, or a paid care worker. These workers leave their countries to earn $400 a week as a nanny in the U.S., sending home $40 a week to pay the caregiver for their own children (Hochschild 2001). The Commercialization of Intimate Life is Hochschild’s book on the subject.

The statistics are startling. Over half the people immigrating to the United States are women, mostly between the ages of 25 and 34. Many of them find employment as domestic workers, and the demand for this type of care in the U.S. is rising. The number of American women in the workforce rose from 28.8 percent in 1950 to 47 percent in 2010 (Waite 1981; United States Department of Labor 2010). Simultaneously, the number of American families that rely on relatives to care for children is steadily decreasing. So the search for trusted, professional care for their children has become a priority worth paying for.

So what is the impact of these “global care chains,” as the article calls them? What does it mean for the children left behind? The American children being cared for? The parents? There are no easy answers to these questions, but it does not mean they should not be asked.

Just as a conscientious consumer would pay attention to the company that makes her sneakers or computer, so too do we need to pay attention to who is sacrificing what to care for core nation children. This is not to say it is exploitative to hire a nanny from overseas. Many women come to the United States expressly for the purpose of finding those jobs that enable them to send enough money home to pay for schooling and a better life. They do this in the hopes that, someday, their own children will have better opportunities (Hochschild 2001).

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Global sociology' conversation and receive update notifications?