| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Many portfolio investment decisions are not as simple as betting that the value of the currency will change in one direction or the other. Instead, they involve firms trying to protect themselves from movements in exchange rates. Imagine you are running a U.S. firm that is exporting to France. You have signed a contract to deliver certain products and will receive 1 million euros a year from now. But you do not know how much this contract will be worth in U.S. dollars, because the dollar/euro exchange rate can fluctuate in the next year. Let’s say you want to know for sure what the contract will be worth, and not take a risk that the euro will be worth less in U.S. dollars than it currently is. You can hedge , which means using a financial transaction to protect yourself against a risk from one of your investments (in this case, currency risk from the contract). Specifically, you can sign a financial contract and pay a fee that guarantees you a certain exchange rate one year from now—regardless of what the market exchange rate is at that time. Now, it is possible that the euro will be worth more in dollars a year from now, so your hedging contract will be unnecessary, and you will have paid a fee for nothing. But if the value of the euro in dollars declines, then you are protected by the hedge. Financial contracts like hedging, where parties wish to be protected against exchange rate movements, also commonly lead to a series of portfolio investments by the firm that is receiving a fee to provide the hedge.

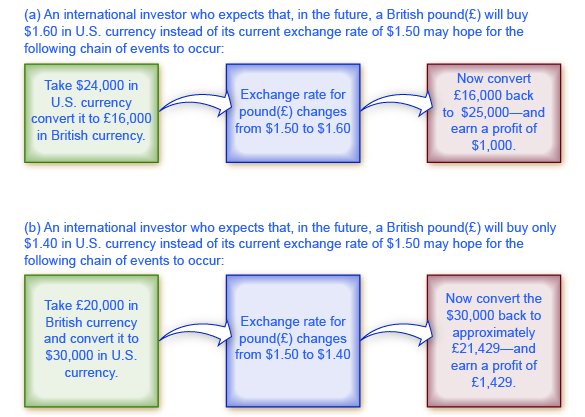

Both foreign direct investment and portfolio investment involve an investor who supplies domestic currency and demands a foreign currency. With portfolio investment less than ten percent of a company is purchased. As such, portfolio investment is often made with a short term focus. With foreign direct investment more than ten percent of a company is purchased and the investor typically assumes some managerial responsibility; thus foreign direct investment tends to have a more long-run focus. As a practical matter, portfolio investments can be withdrawn from a country much more quickly than foreign direct investments. A U.S. portfolio investor who wants to buy or sell bonds issued by the government of the United Kingdom can do so with a phone call or a few clicks of a computer key. However, a U.S. firm that wants to buy or sell a company, such as one that manufactures automobile parts in the United Kingdom, will find that planning and carrying out the transaction takes a few weeks, even months. [link] summarizes the main categories of demanders and suppliers of currency.

| Demand for the U.S. Dollar Comes from… | Supply of the U.S. Dollar Comes from… |

|---|---|

| A U.S. exporting firm that earned foreign currency and is trying to pay U.S.-based expenses | A foreign firm that has sold imported goods in the United States, earned U.S. dollars, and is trying to pay expenses incurred in its home country |

| Foreign tourists visiting the United States | U.S. tourists leaving to visit other countries |

| Foreign investors who wish to make direct investments in the U.S. economy | U.S. investors who want to make foreign direct investments in other countries |

| Foreign investors who wish to make portfolio investments in the U.S. economy | U.S. investors who want to make portfolio investments in other countries |

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Principles of macroeconomics for ap® courses' conversation and receive update notifications?