| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

One critique of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act is that it will create a system of socialized medicine, a term that for many Americans has negative connotations lingering from the Cold War era and earlier. Under a socialized medicine system, the government owns and runs the system. It employs the doctors, nurses, and other staff, and it owns and runs the hospitals (Klein 2009). The best example of socialized medicine is in Great Britain, where the National Health System (NHS) gives free health care to all its residents. And despite some Americans’ knee-jerk reaction to any health care changes that hint of socialism, the United States has one socialized system with the Veterans Health Administration.

It is important to distinguish between socialized medicine, in which the government owns the health care system, and universal health care , which is simply a system that guarantees health care coverage for everyone. Germany, Singapore, and Canada all have universal health care. People often look to Canada’s universal health care system, Medicare, as a model for the system. In Canada, health care is publicly funded and is administered by the separate provincial and territorial governments. However, the care itself comes from private providers. This is the main difference between universal health care and socialized medicine. The Canada Health Act of 1970 required that all health insurance plans must be “available to all eligible Canadian residents, comprehensive in coverage, accessible, portable among provinces, and publicly administered” (International Health Systems Canada 2010).

Heated discussions about socialization of medicine and managed care options seem frivolous when compared with the issues of health care systems in developing or underdeveloped countries. In many countries, per capita income is so low, and governments are so fractured, that health care as we know it is virtually non-existent. Care that people in developed countries take for granted—like hospitals, health care workers, immunizations, antibiotics and other medications, and even sanitary water for drinking and washing—are unavailable to much of the population. Organizations like Doctors Without Borders, UNICEF, and the World Health Organization have played an important role in helping these countries get their most basic health needs met.

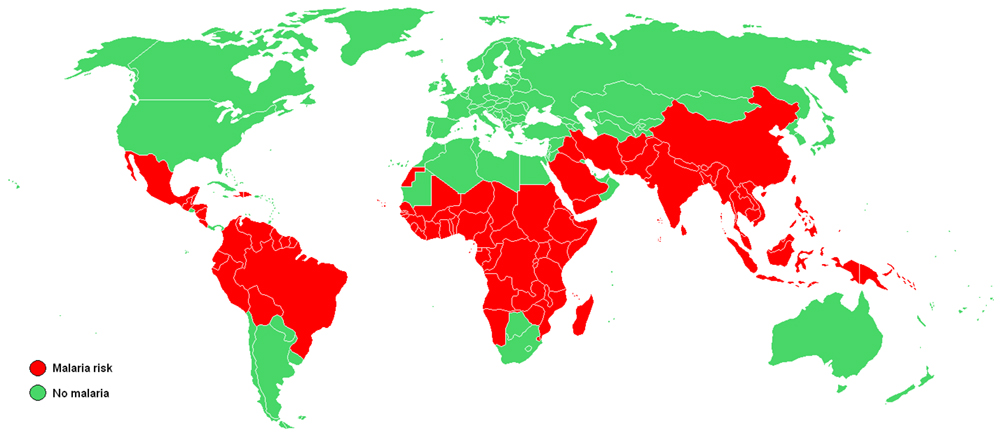

WHO, which is the health arm of the United Nations, set eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in 2000 with the aim of reaching these goals by 2015. Some of the goals deal more broadly with the socioeconomic factors that influence health, but MDGs 4, 5, and 6 all relate specifically to large-scale health concerns, the likes of which most Americans will never contemplate. MDG 4 is to reduce child mortality, MDG 5 aims to improve maternal health, and MDG 6 strives to combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases. The goals may not seem particularly dramatic, but the numbers behind them show how serious they are.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Global sociology' conversation and receive update notifications?