| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Active sites are subject to influences of the local environment. Increasing the environmental temperature generally increases reaction rates, enzyme-catalyzed or otherwise. However, temperatures outside of an optimal range reduce the rate at which an enzyme catalyzes a reaction. Hot temperatures will eventually cause enzymes to denature, an irreversible change in the three-dimensional shape and therefore the function of the enzyme. Enzymes are also suited to function best within a certain pH and salt concentration range, and, as with temperature, extreme pH, and salt concentrations can cause enzymes to denature.

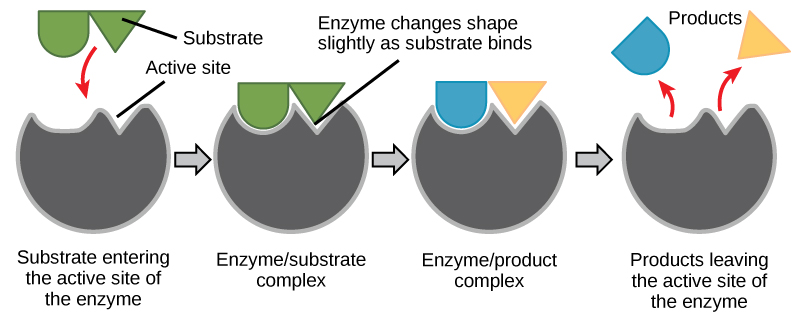

For many years, scientists thought that enzyme-substrate binding took place in a simple “lock and key” fashion. This model asserted that the enzyme and substrate fit together perfectly in one instantaneous step. However, current research supports a model called induced fit ( [link] ). The induced-fit model expands on the lock-and-key model by describing a more dynamic binding between enzyme and substrate. As the enzyme and substrate come together, their interaction causes a mild shift in the enzyme’s structure that forms an ideal binding arrangement between enzyme and substrate.

View an animation of induced fit.

When an enzyme binds its substrate, an enzyme-substrate complex is formed. This complex lowers the activation energy of the reaction and promotes its rapid progression in one of multiple possible ways. On a basic level, enzymes promote chemical reactions that involve more than one substrate by bringing the substrates together in an optimal orientation for reaction. Another way in which enzymes promote the reaction of their substrates is by creating an optimal environment within the active site for the reaction to occur. The chemical properties that emerge from the particular arrangement of amino acid R groups within an active site create the perfect environment for an enzyme’s specific substrates to react.

The enzyme-substrate complex can also lower activation energy by compromising the bond structure so that it is easier to break. Finally, enzymes can also lower activation energies by taking part in the chemical reaction itself. In these cases, it is important to remember that the enzyme will always return to its original state by the completion of the reaction. One of the hallmark properties of enzymes is that they remain ultimately unchanged by the reactions they catalyze. After an enzyme has catalyzed a reaction, it releases its product(s) and can catalyze a new reaction.

It would seem ideal to have a scenario in which all of an organism's enzymes existed in abundant supply and functioned optimally under all cellular conditions, in all cells, at all times. However, a variety of mechanisms ensures that this does not happen. Cellular needs and conditions constantly vary from cell to cell, and change within individual cells over time. The required enzymes of stomach cells differ from those of fat storage cells, skin cells, blood cells, and nerve cells. Furthermore, a digestive organ cell works much harder to process and break down nutrients during the time that closely follows a meal compared with many hours after a meal. As these cellular demands and conditions vary, so must the amounts and functionality of different enzymes.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Concepts in biology (biology 1060 tri-c)' conversation and receive update notifications?