| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

Consider a monopoly firm, comfortably surrounded by barriers to entry so that it need not fear competition from other producers. How will this monopoly choose its profit-maximizing quantity of output, and what price will it charge? Profits for the monopolist, like any firm, will be equal to total revenues minus total costs. The pattern of costs for the monopoly can be analyzed within the same framework as the costs of a perfectly competitive firm —that is, by using total cost, fixed cost, variable cost, marginal cost, average cost, and average variable cost. However, because a monopoly faces no competition, its situation and its decision process will differ from that of a perfectly competitive firm. (The Clear it Up feature discusses how hard it is sometimes to define “market” in a monopoly situation.)

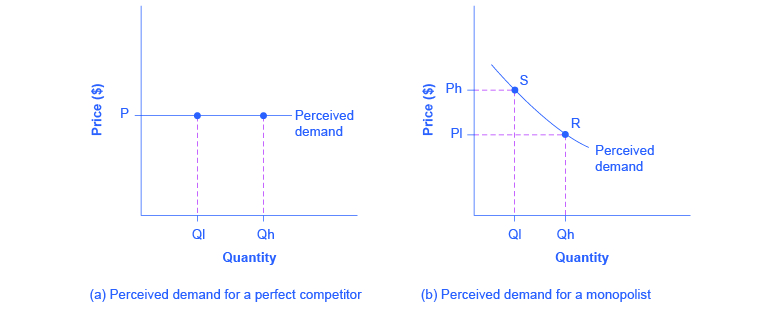

A perfectly competitive firm acts as a price taker, so its calculation of total revenue is made by taking the given market price and multiplying it by the quantity of output that the firm chooses. The demand curve as it is perceived by a perfectly competitive firm appears in [link] (a). The flat perceived demand curve means that, from the viewpoint of the perfectly competitive firm, it could sell either a relatively low quantity like Ql or a relatively high quantity like Qh at the market price P.

A monopoly is a firm that sells all or nearly all of the goods and services in a given market. But what defines the “market”?

In a famous 1947 case, the federal government accused the DuPont company of having a monopoly in the cellophane market, pointing out that DuPont produced 75% of the cellophane in the United States. DuPont countered that even though it had a 75% market share in cellophane, it had less than a 20% share of the “flexible packaging materials,” which includes all other moisture-proof papers, films, and foils. In 1956, after years of legal appeals, the U.S. Supreme Court held that the broader market definition was more appropriate, and the case against DuPont was dismissed.

Questions over how to define the market continue today. True, Microsoft in the 1990s had a dominant share of the software for computer operating systems, but in the total market for all computer software and services, including everything from games to scientific programs, the Microsoft share was only about 14% in 2014. The Greyhound bus company may have a near-monopoly on the market for intercity bus transportation, but it is only a small share of the market for intercity transportation if that market includes private cars, airplanes, and railroad service. DeBeers has a monopoly in diamonds, but it is a much smaller share of the total market for precious gemstones and an even smaller share of the total market for jewelry. A small town in the country may have only one gas station: is this gas station a “monopoly,” or does it compete with gas stations that might be five, 10, or 50 miles away?

In general, if a firm produces a product without close substitutes, then the firm can be considered a monopoly producer in a single market. But if buyers have a range of similar—even if not identical—options available from other firms, then the firm is not a monopoly. Still, arguments over whether substitutes are close or not close can be controversial.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Openstax microeconomics in ten weeks' conversation and receive update notifications?