| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

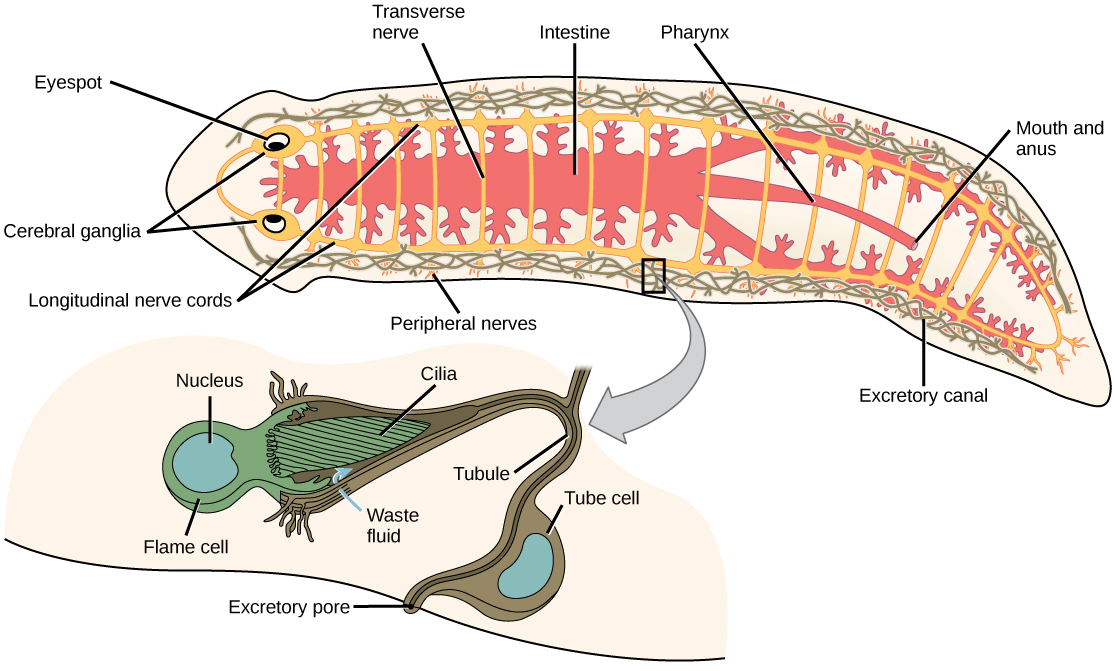

Since there is no circulatory or respiratory system, gas and nutrient exchange is dependent on diffusion and intercellular junctions. This necessarily limits the thickness of the body in these organisms, constraining them to be “flat” worms. Most flatworm species are monoecious (hermaphroditic, possessing both sets of sex organs), and fertilization is typically internal. Asexual reproduction is common in some groups in which an entire organism can be regenerated from just a part of itself.

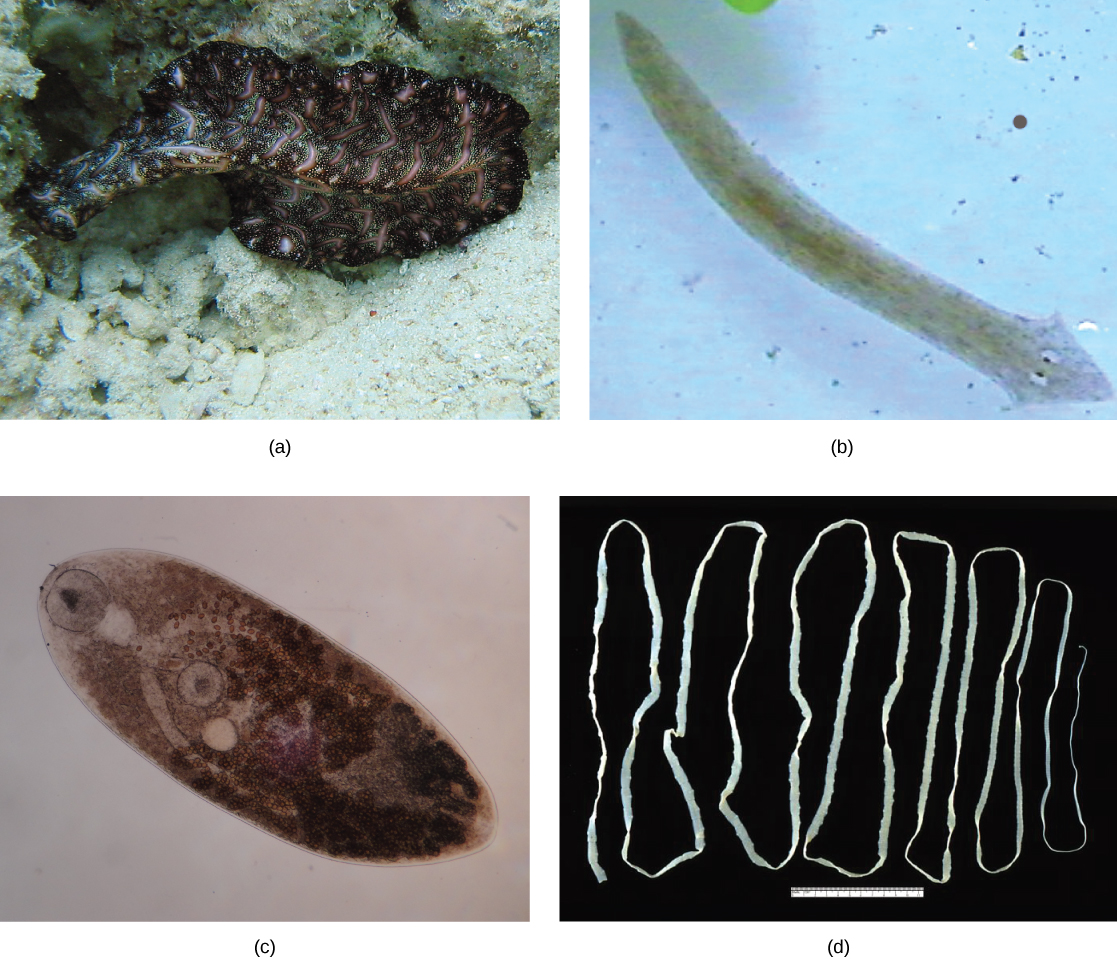

Flatworms are traditionally divided into four classes: Turbellaria, Monogenea, Trematoda, and Cestoda ( [link] ). The turbellarians include mainly free-living marine species, although some species live in freshwater or moist terrestrial environments. The simple planarians found in freshwater ponds and aquaria are examples. The epidermal layer of the underside of turbellarians is ciliated, and this helps them move. Some turbellarians are capable of remarkable feats of regeneration in which they may regrow the body, even from a small fragment.

The monogeneans are external parasites mostly of fish with life cycles consisting of a free-swimming larva that attaches to a fish to begin transformation to the parasitic adult form. They have only one host during their life, typically of just one species. The worms may produce enzymes that digest the host tissues or graze on surface mucus and skin particles. Most monogeneans are hermaphroditic, but the sperm develop first, and it is typical for them to mate between individuals and not to self-fertilize.

The trematodes, or flukes, are internal parasites of mollusks and many other groups, including humans. Trematodes have complex life cycles that involve a primary host in which sexual reproduction occurs and one or more secondary hosts in which asexual reproduction occurs. The primary host is almost always a mollusk. Trematodes are responsible for serious human diseases including schistosomiasis, caused by a blood fluke ( Schistosoma ). The disease infects an estimated 200 million people in the tropics and leads to organ damage and chronic symptoms including fatigue. Infection occurs when a human enters the water, and a larva, released from the primary snail host, locates and penetrates the skin. The parasite infects various organs in the body and feeds on red blood cells before reproducing. Many of the eggs are released in feces and find their way into a waterway where they are able to reinfect the primary snail host.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Natural history supplemental' conversation and receive update notifications?