| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Yet even after Galileo and Newton, there remained another question: Were living things somehow different from rocks and water and stars? Did animate and inanimate matter differ in some fundamental way? the "vitalists" claimed that animate matter had some special essence, an intangible spirit or soul, while the "mechanists" argued that living things were elaborate machines and obeyed precisely the same laws of physics and chemistry as did inanimate material.Alan Lightman, "Our Place in the Universe", Harper's Magazine , December 2012.

One of the greatest scientists of all time, Louis Pasteur, believed that metabolic reactions such as fermentation could only occur in living cells. This perspective was widely shared by scientists of the 19th Century. Thus one of the first damaging blows to the vitalist perspective came in the late 19th Century, when Eduard Buchner showed that a cell-free extract from yeast could carry out the synthesis of ethanol from glucose (alcoholic fermentation). Whole cells were not required for this process. These extracts were called " enzymes ", which derives from the Greek words "en" (in) + "zyme" (yeast). Buchner demonstrated that there was something "in yeast", as opposed to the yeast cells themselves, that could convert glucose to ethanol. The subsequent work of many other scientists has built on this simple concept - cells contain substances that catalyze reactions, and these substances can be studied apart from the cells themselves.

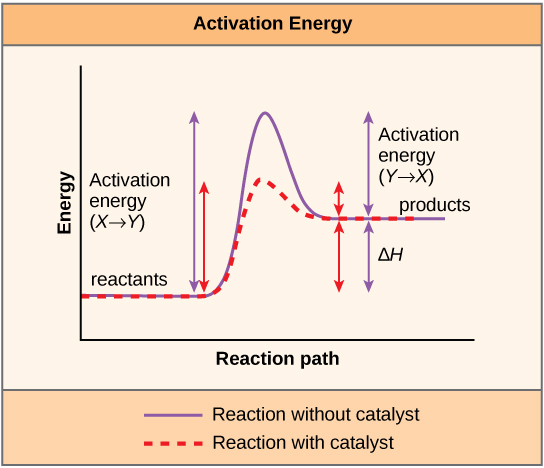

A substance that helps a chemical reaction to occur is a catalyst , and the special molecules that catalyze biochemical reactions are called enzymes. Almost all enzymes are proteins, made up of chains of amino acids, and they perform the critical task of lowering the activation energies of chemical reactions inside the cell. Enzymes do this by binding to the reactant molecules, and holding them in such a way as to make the chemical bond-breaking and bond-forming processes take place more readily. It is important to remember that enzymes don’t change the ∆G of a reaction. In other words, they don’t change whether a reaction is exergonic (spontaneous) or endergonic. This is because they don’t change the free energy of the reactants or products. They only reduce the activation energy required to reach the transition state ( [link] ).

The chemical reactants to which an enzyme binds are the enzyme’s substrates . There may be one or more substrates, depending on the particular chemical reaction. In some reactions, a single-reactant substrate is broken down into multiple products. In others, two substrates may come together to create one larger molecule. Two reactants might also enter a reaction, both become modified, and leave the reaction as two products. The location within the enzyme where the substrate binds is called the enzyme’s active site . The active site is where the “action” happens, so to speak. Since enzymes are proteins, there is a unique combination of amino acid residues (also called side chains, or R groups) within the active site. Each residue is characterized by different properties. Residues can be large or small, weakly acidic or basic, hydrophilic or hydrophobic, positively or negatively charged, or neutral. The unique combination of amino acids, their positions, sequences, structures, and properties, creates a very specific chemical environment within the active site. This specific environment is suited to bind, albeit briefly, to a specific chemical substrate (or substrates). Due to this jigsaw puzzle-like match between an enzyme and its substrates (which adapts to find the best fit between the transition state and the active site), enzymes are known for their specificity. The “best fit” results from the shape and the amino acid functional group’s attraction to the substrate. There is a specifically matched enzyme for each substrate and, thus, for each chemical reaction; however, there is flexibility as well.

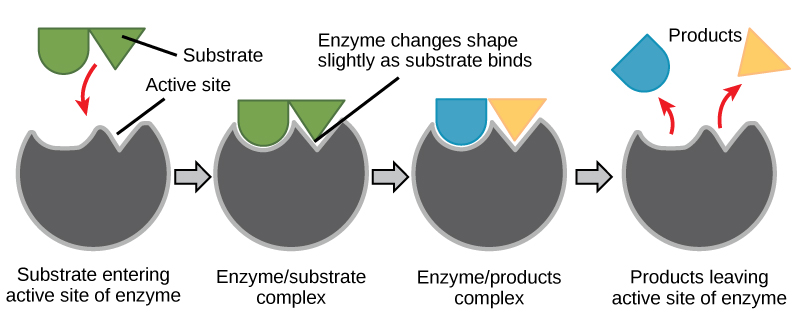

For many years, scientists thought that enzyme-substrate binding took place in a simple “lock-and-key” fashion. This model asserted that the enzyme and substrate fit together perfectly in one instantaneous step. However, current research supports a more refined view called induced fit ( [link] ). The induced-fit model expands upon the lock-and-key model by describing a more dynamic interaction between enzyme and substrate. As the enzyme and substrate come together, their interaction causes a mild shift in the enzyme’s structure that confirms an ideal binding arrangement between the enzyme and the transition state of the substrate. This ideal binding maximizes the enzyme’s ability to catalyze its reaction.

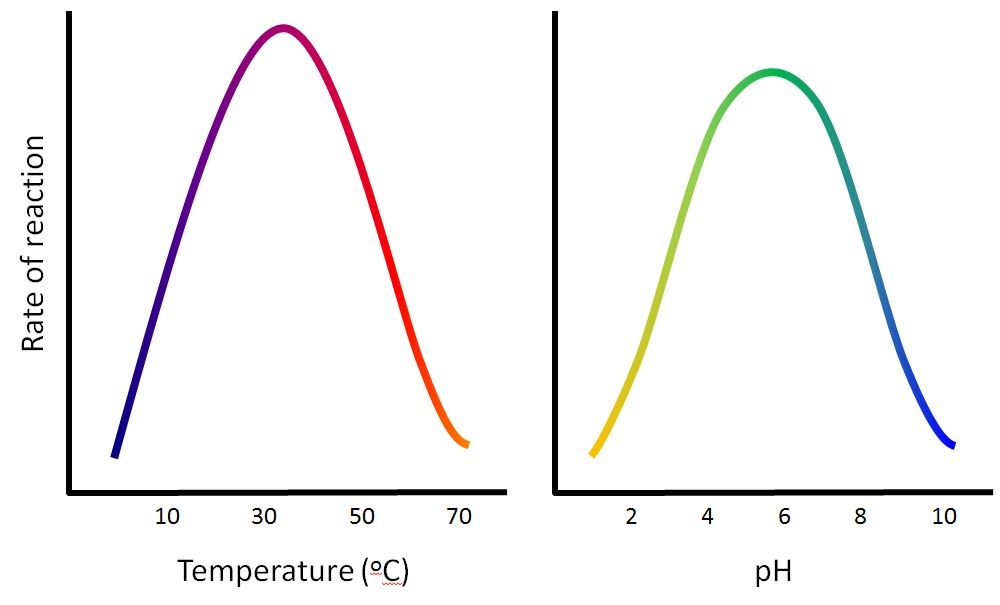

When an enzyme binds its substrate, an enzyme-substrate complex is formed. This complex lowers the activation energy of the reaction and promotes its rapid progression in one of many ways. On a basic level, enzymes promote chemical reactions that involve more than one substrate by bringing the substrates together in an optimal orientation. The appropriate region (atoms and bonds) of one molecule is juxtaposed to the appropriate region of the other molecule with which it must react. Another way in which enzymes promote the reaction of their substrates is by creating an optimal environment within the active site for the reaction to occur. Certain chemical reactions might proceed best in a slightly acidic or non-polar environment. The chemical properties that emerge from the particular arrangement of amino acid residues within an active site create the perfect environment for an enzyme’s specific substrates to react.

You’ve learned that the activation energy required for many reactions includes the energy involved in manipulating or slightly contorting chemical bonds so that they can easily break and allow others to reform. Enzymatic action can aid this process. The enzyme-substrate complex can lower the activation energy by contorting substrate molecules in such a way as to facilitate bond-breaking, helping to reach the transition state. Finally, enzymes can also lower activation energies by taking part in the chemical reaction itself. The amino acid residues can provide certain ions or chemical groups that actually form covalent bonds with substrate molecules as a necessary step of the reaction process. In these cases, it is important to remember that the enzyme will always return to its original state at the completion of the reaction. One of the hallmark properties of enzymes is that they remain ultimately unchanged by the reactions they catalyze. After an enzyme is done catalyzing a reaction, it releases its product(s).

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Principles of biology' conversation and receive update notifications?