| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

While the pre-mRNA is still being synthesized, a 7-methylguanosine cap is added to the 5' end of the growing transcript by a phosphate linkage. This moiety (functional group) protects the nascent mRNA from degradation. In addition, factors involved in protein synthesis recognize the cap to help initiate translation by ribosomes.

Once elongation is complete, the pre-mRNA is cleaved by an endonuclease between an AAUAAA consensus sequence and a GU-rich sequence, leaving the AAUAAA sequence on the pre-mRNA. An enzyme called poly-A polymerase then adds a string of approximately 200 A residues, called the poly-A tail . This modification further protects the pre-mRNA from degradation and signals the export of the cellular factors that the transcript needs to the cytoplasm.

Eukaryotic genes are composed of exons , which correspond to protein-coding sequences ( ex- on signifies that they are ex pressed), and int ervening sequences called introns ( int- ron denotes their int ervening role), which may be involved in gene regulation but are removed from the pre-mRNA during processing. Intron sequences in mRNA do not encode functional proteins.

The discovery of introns came as a surprise to researchers in the 1970s who expected that pre-mRNAs would specify protein sequences without further processing, as they had observed in prokaryotes. The genes of higher eukaryotes very often contain one or more introns. These regions may correspond to regulatory sequences; however, the biological significance of having many introns or having very long introns in a gene is unclear. It is possible that introns slow down gene expression because it takes longer to transcribe pre-mRNAs with lots of introns. Alternatively, introns may be nonfunctional sequence remnants left over from the fusion of ancient genes throughout evolution. This is supported by the fact that separate exons often encode separate protein subunits or domains. For the most part, the sequences of introns can be mutated without ultimately affecting the protein product.

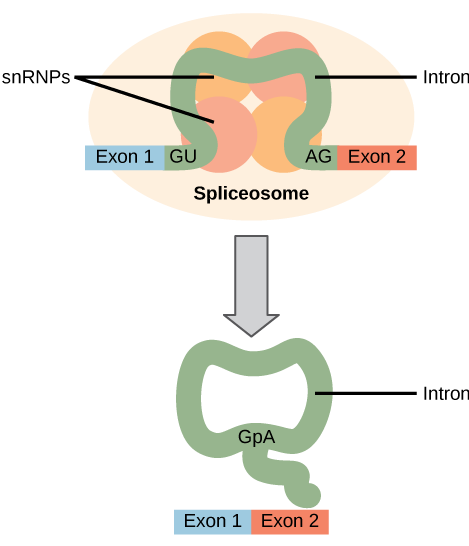

All of a pre-mRNA’s introns must be completely and precisely removed before protein synthesis. If the process errs by even a single nucleotide, the reading frame of the rejoined exons would shift, and the resulting protein would be dysfunctional. The process of removing introns and reconnecting exons is called splicing ( [link] ). Introns are removed and degraded while the pre-mRNA is still in the nucleus. Splicing occurs by a sequence-specific mechanism that ensures introns will be removed and exons rejoined with the accuracy and precision of a single nucleotide. The splicing of pre-mRNAs is conducted by complexes of proteins and RNA molecules called spliceosomes.

Errors in splicing are implicated in cancers and other human diseases. What kinds of mutations might lead to splicing errors? Think of different possible outcomes if splicing errors occur.

Note that more than 70 individual introns can be present, and each has to undergo the process of splicing—in addition to 5' capping and the addition of a poly-A tail—just to generate a single, translatable mRNA molecule.

See how introns are removed during RNA splicing at this website .

The tRNAs and rRNAs are structural molecules that have roles in protein synthesis; however, these RNAs are not themselves translated. Pre-rRNAs are transcribed, processed, and assembled into ribosomes in the nucleolus. Pre-tRNAs are transcribed and processed in the nucleus and then released into the cytoplasm where they are linked to free amino acids for protein synthesis.

Most of the tRNAs and rRNAs in eukaryotes and prokaryotes are first transcribed as a long precursor molecule that spans multiple rRNAs or tRNAs. Enzymes then cleave the precursors into subunits corresponding to each structural RNA. Some of the bases of pre-rRNAs are methylated; that is, a –CH 3 moiety (methyl functional group) is added for stability. Pre-tRNA molecules also undergo methylation. As with pre-mRNAs, subunit excision occurs in eukaryotic pre-RNAs destined to become tRNAs or rRNAs.

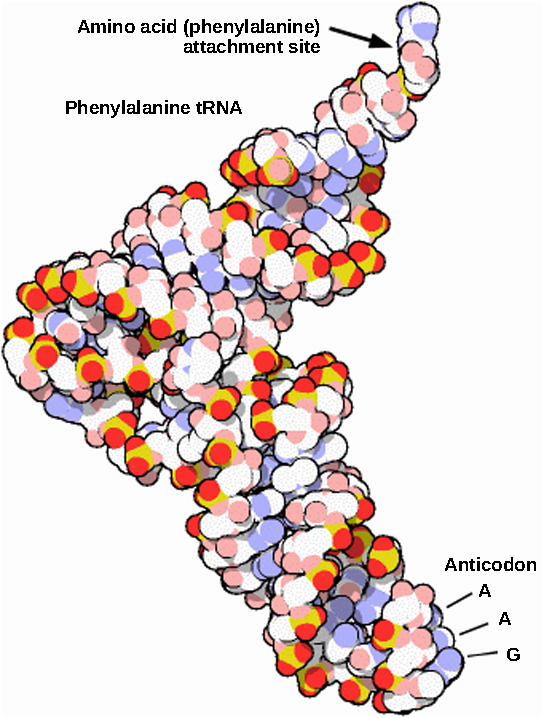

Mature rRNAs make up approximately 50 percent of each ribosome. Some of a ribosome’s RNA molecules are purely structural, whereas others have catalytic or binding activities. Mature tRNAs take on a three-dimensional structure through intramolecular hydrogen bonding to position the amino acid binding site at one end and the anticodon at the other end ( [link] ). The anticodon is a three-nucleotide sequence in a tRNA that interacts with an mRNA codon through complementary base pairing.

Eukaryotic pre-mRNAs are modified with a 5' methylguanosine cap and a poly-A tail. These structures protect the mature mRNA from degradation and help export it from the nucleus. Pre-mRNAs also undergo splicing, in which introns are removed and exons are reconnected with single-nucleotide accuracy. Only finished mRNAs that have undergone 5' capping, 3' polyadenylation, and intron splicing are exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. Pre-rRNAs and pre-tRNAs may be processed by intramolecular cleavage, splicing, methylation, and chemical conversion of nucleotides. Rarely, RNA editing is also performed to insert missing bases after an mRNA has been synthesized.

[link] Errors in splicing are implicated in cancers and other human diseases. What kinds of mutations might lead to splicing errors? Think of different possible outcomes if splicing errors occur.

[link] Mutations in the spliceosome recognition sequence at each end of the intron, or in the proteins and RNAs that make up the spliceosome, may impair splicing. Mutations may also add new spliceosome recognition sites. Splicing errors could lead to introns being retained in spliced RNA, exons being excised, or changes in the location of the splice site.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Cell biology' conversation and receive update notifications?