| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

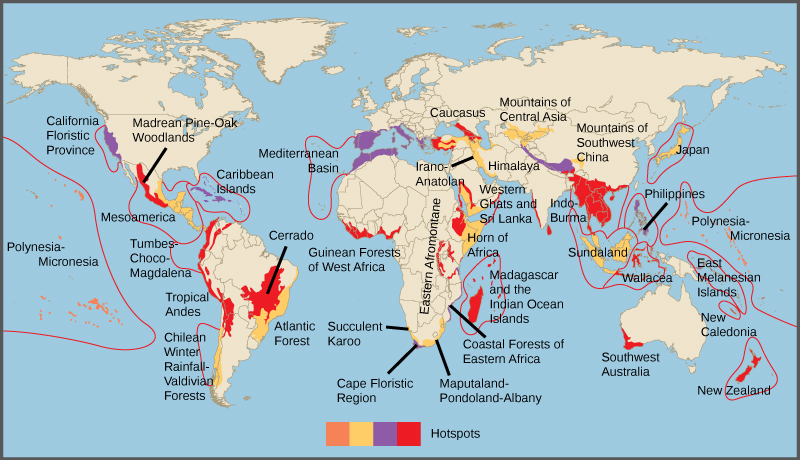

A biodiversity hotspot is a conservation concept developed by Norman Myers in 1988. Hotspots are geographical areas that contain high numbers of endemic species. The purpose of the concept was to identify important locations on the planet for conservation efforts, a kind of conservation triage. By protecting hotspots, governments are able to protect a larger number of species. The original criteria for a hotspot included the presence of 1500 or more species of endemic plants and 70 percent of the area disturbed by human activity. There are now 34 biodiversity hotspots ( [link] ) that contain large numbers of endemic species, which include half of Earth’s endemic plants.

There has been extensive research into optimal preserve designs for maintaining biodiversity. The fundamental principles behind much of the research have come from the seminal theoretical work of Robert H. MacArthur and Edward O. Wilson published in 1967 on island biogeography. Robert H. MacArthur and Edward O. Wilson, E. O., The Theory of Island Biogeography (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1967). This work sought to understand the factors affecting biodiversity on islands. Conservation preserves can be seen as “islands” of habitat within “an ocean” of non-habitat. In general, large preserves are better because they support more species, including species with large home ranges; they have more core area of optimal habitat for individual species; they have more niches to support more species; and they attract more species because they can be found and reached more easily.

Preserves perform better when there are partially protected buffer zones around them of suboptimal habitat. The buffer allows organisms to exit the boundaries of the preserve without immediate negative consequences from hunting or lack of resources. One large preserve is better than the same area of several smaller preserves because there is more core habitat unaffected by less hospitable ecosystems outside the preserve boundary. For this same reason, preserves in the shape of a square or circle will be better than a preserve with many thin “arms.” If preserves must be smaller, then providing wildlife corridors between them so that species and their genes can move between the preserves; for example, preserves along rivers and streams will make the smaller preserves behave more like a large one. All of these factors are taken into consideration when planning the nature of a preserve before the land is set aside.

In addition to the physical specifications of a preserve, there are a variety of regulations related to the use of a preserve. These can include anything from timber extraction, mineral extraction, regulated hunting, human habitation, and nondestructive human recreation. Many of the decisions to include these other uses are made based on political pressures rather than conservation considerations. On the other hand, in some cases, wildlife protection policies have been so strict that subsistence-living indigenous populations have been forced from ancestral lands that fell within a preserve. In other cases, even if a preserve is designed to protect wildlife, if the protections are not or cannot be enforced, the preserve status will have little meaning in the face of illegal poaching and timber extraction. This is a widespread problem with preserves in the tropics.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Concepts in biology (biology 1060 tri-c)' conversation and receive update notifications?