| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Only certain materials, such as iron, cobalt, nickel, and gadolinium, exhibit strong magnetic effects. Such materials are called ferromagnetic , after the Latin word for iron, ferrum . A group of materials made from the alloys of the rare earth elements are also used as strong and permanent magnets; a popular one is neodymium. Other materials exhibit weak magnetic effects, which are detectable only with sensitive instruments. Not only do ferromagnetic materials respond strongly to magnets (the way iron is attracted to magnets), they can also be magnetized themselves—that is, they can be induced to be magnetic or made into permanent magnets.

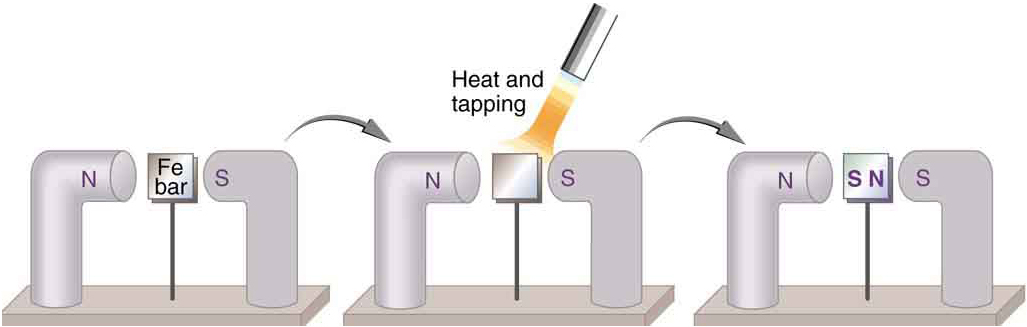

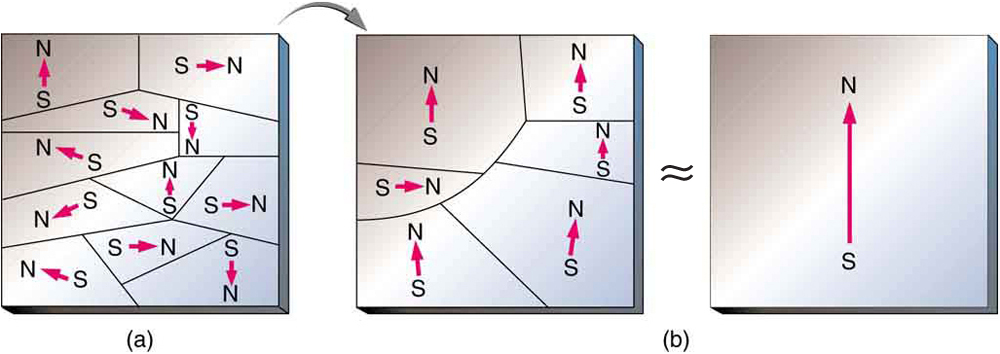

When a magnet is brought near a previously unmagnetized ferromagnetic material, it causes local magnetization of the material with unlike poles closest, as in [link] . (This results in the attraction of the previously unmagnetized material to the magnet.) What happens on a microscopic scale is illustrated in [link] . The regions within the material called domains act like small bar magnets. Within domains, the poles of individual atoms are aligned. Each atom acts like a tiny bar magnet. Domains are small and randomly oriented in an unmagnetized ferromagnetic object. In response to an external magnetic field, the domains may grow to millimeter size, aligning themselves as shown in [link] (b). This induced magnetization can be made permanent if the material is heated and then cooled, or simply tapped in the presence of other magnets.

Conversely, a permanent magnet can be demagnetized by hard blows or by heating it in the absence of another magnet. Increased thermal motion at higher temperature can disrupt and randomize the orientation and the size of the domains. There is a well-defined temperature for ferromagnetic materials, which is called the Curie temperature , above which they cannot be magnetized. The Curie temperature for iron is 1043 K , which is well above room temperature. There are several elements and alloys that have Curie temperatures much lower than room temperature and are ferromagnetic only below those temperatures.

Early in the 19th century, it was discovered that electrical currents cause magnetic effects. The first significant observation was by the Danish scientist Hans Christian Oersted (1777–1851), who found that a compass needle was deflected by a current-carrying wire. This was the first significant evidence that the movement of charges had any connection with magnets. Electromagnetism is the use of electric current to make magnets. These temporarily induced magnets are called electromagnets . Electromagnets are employed for everything from a wrecking yard crane that lifts scrapped cars to controlling the beam of a 90-km-circumference particle accelerator to the magnets in medical imaging machines (See [link] ).

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'College physics (engineering physics 2, tuas)' conversation and receive update notifications?