| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

In the two centuries since Dalton developed his ideas, scientists have made significant progress in furthering our understanding of atomic theory. Much of this came from the results of several seminal experiments that revealed the details of the internal structure of atoms. Here, we will discuss some of those key developments, with an emphasis on application of the scientific method, as well as understanding how the experimental evidence was analyzed. While the historical persons and dates behind these experiments can be quite interesting, it is most important to understand the concepts resulting from their work.

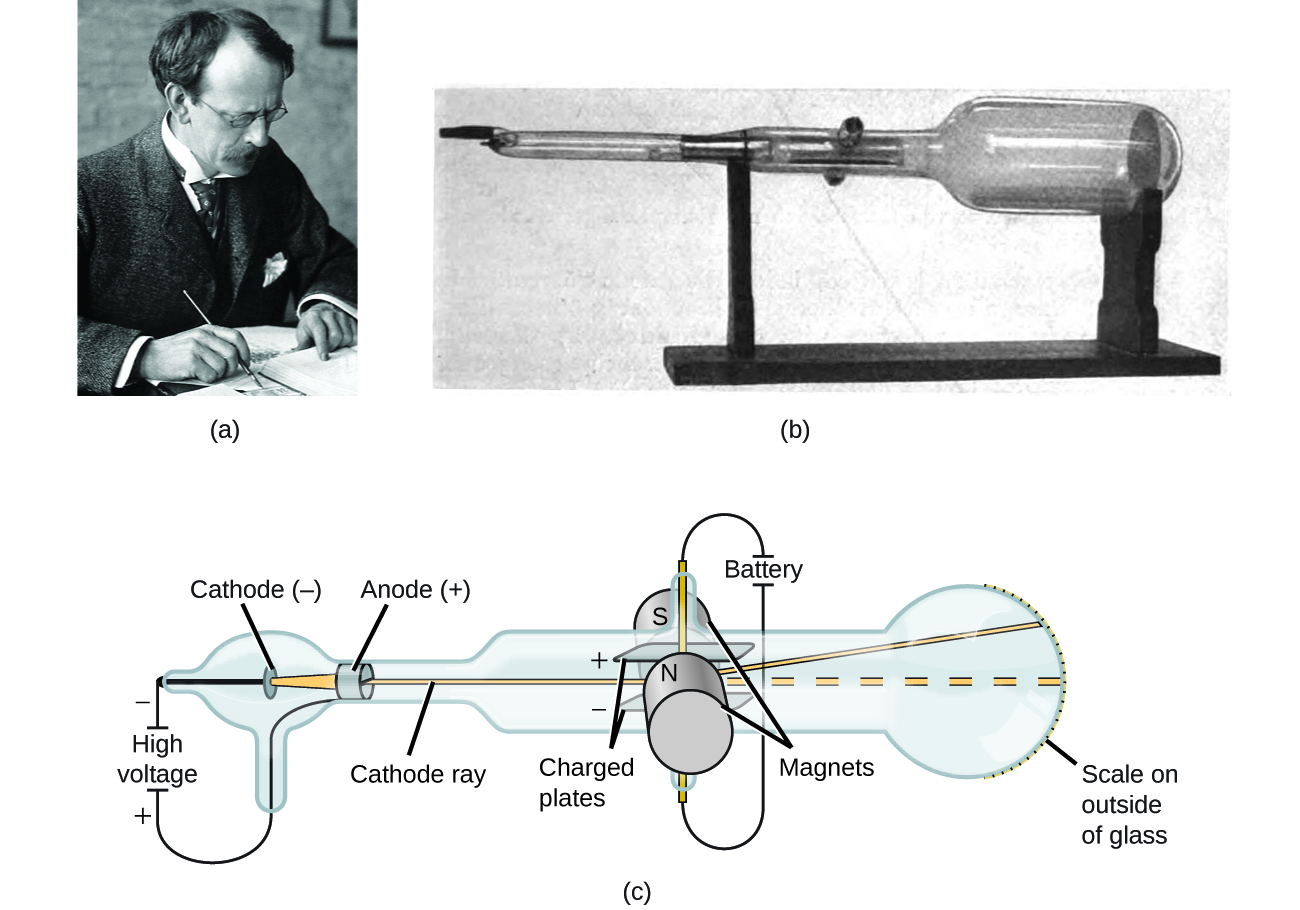

If matter were composed of atoms, what were atoms composed of? Were they the smallest particles, or was there something smaller? In the late 1800s, a number of scientists interested in questions like these investigated the electrical discharges that could be produced in low-pressure gases, with the most significant discovery made by English physicist J. J. Thomson using a cathode ray tube. This apparatus consisted of a sealed glass tube from which almost all the air had been removed; the tube contained two metal electrodes. When high voltage was applied across the electrodes, a visible beam called a cathode ray appeared between them. This beam was deflected toward the positive charge and away from the negative charge, and was produced in the same way with identical properties when different metals were used for the electrodes. In similar experiments, the ray was simultaneously deflected by an applied magnetic field, and measurements of the extent of deflection and the magnetic field strength allowed Thomson to calculate the charge-to-mass ratio of the cathode ray particles. The results of these measurements indicated that these particles were much lighter than atoms ( [link] ).

Based on his observations, here is what Thomson proposed and why: The particles are attracted by positive (+) charges and repelled by negative (−) charges, so they must be negatively charged (like charges repel and unlike charges attract); they are less massive than atoms and indistinguishable, regardless of the source material, so they must be fundamental, subatomic constituents of all atoms. Although controversial at the time, Thomson’s idea was gradually accepted, and his cathode ray particle is what we now call an electron , a negatively charged, subatomic particle with a mass more than one thousand-times less that of an atom. The term “electron” was coined in 1891 by Irish physicist George Stoney, from “ electr ic i on .”

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Ut austin - principles of chemistry' conversation and receive update notifications?