| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

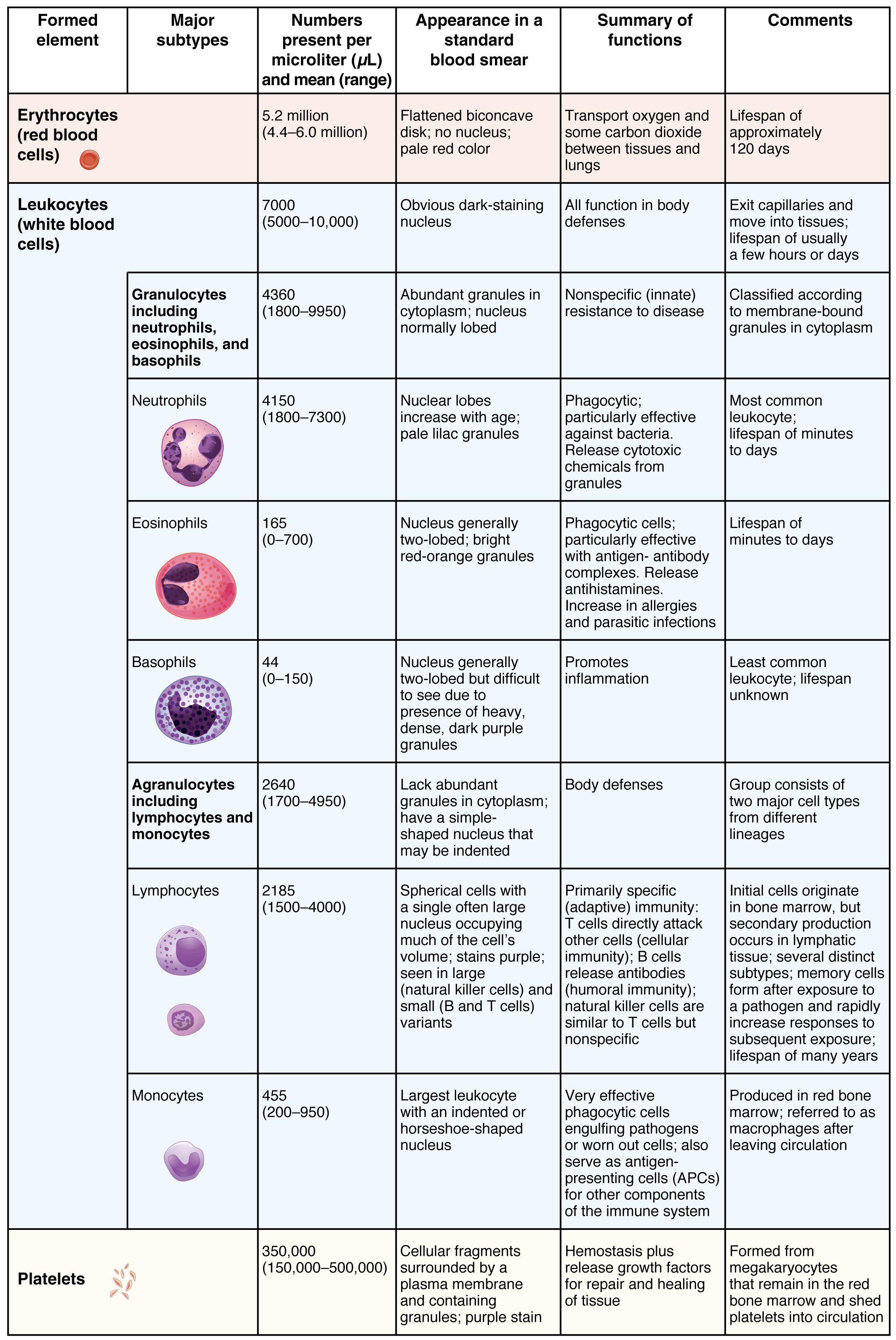

The erythrocyte , commonly known as a red blood cell (or RBC), is by far the most common formed element: A single drop of blood contains millions of erythrocytes and just thousands of leukocytes. Specifically, males have about 5.4 million erythrocytes per microliter ( µ L) of blood, and females have approximately 4.8 million per µ L. In fact, erythrocytes are estimated to make up about 25 percent of the total cells in the body. As you can imagine, they are quite small cells, with a mean diameter of only about 7–8 micrometers ( µ m) ( [link] ). The primary functions of erythrocytes are to pick up inhaled oxygen from the lungs and transport it to the body’s tissues, and to pick up some (about 24 percent) carbon dioxide waste at the tissues and transport it to the lungs for exhalation. Erythrocytes remain within the vascular network. Although leukocytes typically leave the blood vessels to perform their defensive functions, movement of erythrocytes from the blood vessels is abnormal.

As an erythrocyte matures in the red bone marrow, it extrudes its nucleus and most of its other organelles. During the first day or two that it is in the circulation, an immature erythrocyte, known as a reticulocyte , will still typically contain remnants of organelles. Reticulocytes should comprise approximately 1–2 percent of the erythrocyte count and provide a rough estimate of the rate of RBC production, with abnormally low or high rates indicating deviations in the production of these cells. These remnants, primarily of networks (reticulum) of ribosomes, are quickly shed, however, and mature, circulating erythrocytes have few internal cellular structural components. Lacking mitochondria, for example, they rely on anaerobic respiration. This means that they do not utilize any of the oxygen they are transporting, so they can deliver it all to the tissues. They also lack endoplasmic reticula and do not synthesize proteins. Erythrocytes do, however, contain some structural proteins that help the blood cells maintain their unique structure and enable them to change their shape to squeeze through capillaries. This includes the protein spectrin, a cytoskeletal protein element.

Erythrocytes are biconcave disks; that is, they are plump at their periphery and very thin in the center ( [link] ). Since they lack most organelles, there is more interior space for the presence of the hemoglobin molecules that, as you will see shortly, transport gases. The biconcave shape also provides a greater surface area across which gas exchange can occur, relative to its volume; a sphere of a similar diameter would have a lower surface area-to-volume ratio. In the capillaries, the oxygen carried by the erythrocytes can diffuse into the plasma and then through the capillary walls to reach the cells, whereas some of the carbon dioxide produced by the cells as a waste product diffuses into the capillaries to be picked up by the erythrocytes. Capillary beds are extremely narrow, slowing the passage of the erythrocytes and providing an extended opportunity for gas exchange to occur. However, the space within capillaries can be so minute that, despite their own small size, erythrocytes may have to fold in on themselves if they are to make their way through. Fortunately, their structural proteins like spectrin are flexible, allowing them to bend over themselves to a surprising degree, then spring back again when they enter a wider vessel. In wider vessels, erythrocytes may stack up much like a roll of coins, forming a rouleaux, from the French word for “roll.”

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the '101-321-va - vertebrate form and function ii' conversation and receive update notifications?