| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

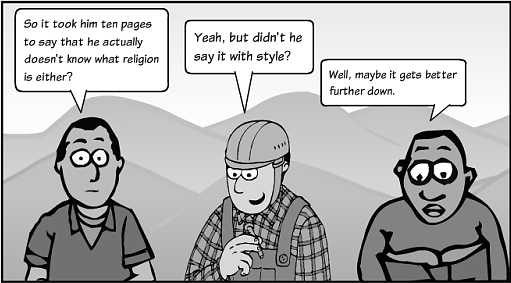

Consider the work of the philosopher Wittgenstein. As a young philosopher, he engaged in highly abstract work on logic, but as he grew older he became interested in concepts and ideas that seemed to defy definition. Wittgenstein developed his philosophy using "game" as his first example. What, he asked, is a game? Many games are played with balls and sticks, but chess is a game, yet it involves neither. Games are played for fun, unless you happen to be a professional sportsman who does it for the money even when you are injured. Games can involve competition, but some others stress cooperation. And so on. In the end, he decided that "game" could not be reduced to one single defining attribute. Instead, it was the sum total of all its attributes, a family resemblance . If one looked at a human activity and saw that the majority of its properties could be found in the list that together made up the definition of "game", then one would be justified in saying that that particular activity was a game. But it was not necessary for all of them to be there.

Can you see how the same is true of religion? It is a big composite of ideas, customs and practices, all sharing a certain "family resemblance", but no single one being so dominant that it alone makes the whole thing "religious". It is all those little things taken together that religion its identity, and if one of those little things falls out of place, this does not make the whole complex invalid. For centuries, religious thinkers have been telling us that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. It turns out that this is equally true for religion itself.

In fact, this understanding of what religion is closely reflects the evolution of the concept. When the early European explorers set out on their voyages in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, they already had some idea of what religion was. This notion was derived mostly from Christianity, but they were also aware of Judaism and Islam, even if they regarded these as false religions. When they reached India, they encountered Hinduism. This ancient civilisation had systematised beliefs and practices that bore a sufficient resemblance to what they were used to at home for them to refer to Hinduism as the "religion" of the Indian people. The same was true when, later, they reached China and the Americas. In each of these cases, there were separate social structures that were not necessarily identical to European religion, but which bore a certain "family resemblance" to it. With each discovery of a new "religion", the very term itself was widened and it became easier and easier to describe a newly-discovered social phenomenon as "religious".

Sometimes this process would break down, of course - some of the early Christian missionaries to Southern Africa would write in their letters home that the indigenous people of Africa had no religion! Actually, what happened was that those activities that would be considered "religious" in western society were, in African communities, so tightly integrated with the rest of social life as to present a seamless whole to the observer. To some extent, this is also true of Judaism and Hinduism, as we have seen. Even in modern western society, it is not always easy to say where religion stops and, say, politics begins.

If we stop looking for one small defining property that makes religion what it is, the problem of differences between religions immediately starts to fade away. It is no longer a problem, but rather in itself a glorious expression of the human capacity for making sense of the world. Religion may or may not be divine in origin, but it certainly is human in execution. That people living in different times and places should have responded to their experience of life and death in ways different from mine, but still broadly recognisable as religious, is not a scandal of philosophy, but a celebration of human ingenuity and adaptability. I do not have to adopt another religious system in its totality, but I can still appreciate the beauty and grandeur of that system.

And the same must then be true in our personal religious practice. My bona fide religious experience is completely valid within the framework of my religious tradition, and so is your religious experience within the framework of yours. The fact that my religious experience is not the same as yours, or that our religious systems contradict each other on many specific points, does not change the fact that on the experiential level we have both experienced a life-altering event of the deepest possible meaning. All of us, the Catholic and the Copt, the Buddhist and the Baptist, stand before the Great Mystery, begging bowl in hand, dumbfounded by the greatness of what we can see only dimly.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Learning about religion' conversation and receive update notifications?