| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

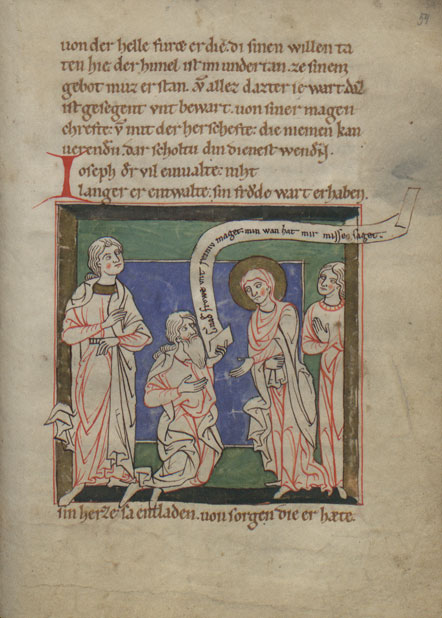

Here the angel is the supernatural agent who speaks to the sleeping Joseph to remind him of his earlier experience at the Temple: “His goodness chose you. / Now serve her with steady courage, / and hold her in loving protection” [sîn gůte dich erwelt hat / nu dien ir mit staetem mute / vnd habes in lieber hůte; ll. 3138-40]. Joseph immediately seeks Mary out to apologize (Fig. 18; fol. 54r). In a composition that echoes but significantly revises the wedding miniature, Mary extends her hand to forgive Joseph, not to submit to him. He kneels before her, communicating bodily the shift in power. The way Mary leans her body forward and stretches out her hand toward his embodies her empathetic response; their hands will clasp, sealing the affective bond that now characterizes this marriage and overwrites the earlier wrist grasp. This sustained attention to the resolution of a rift within their marriage offers them to the reader-viewer as a model for dealing with tense, emotion-filled conflicts in a marital relationship.

This plot episode also addresses the issue of genealogy raised by the first miniature in the manuscript. The angel addresses Joseph as “son of David” [Josep kind Dauit; l. 3123], identifying him as a descendent of Jesse along with Mary, and goes on to say of Mary, “She is above all women / and must always remain / mother and holy maiden: / God grants her the honor” [sie ist ob allen wiben / vnd můz iemer beliben / muter unde maeit here: / got lihet ir die ere; ll, 3129-32]. The words on his banderole articulate his acceptance of their import: “Gracious lady and pure virgin, my assumption led me into error” [Gnade frowe unt reiniu maget. / min wan hat mir misse saget]. That assumption, according to words assigned to him in the text, was the sin of mistrusting her body because of any earthly man. He now knows that God took her as his spouse [ll. 3164-74]. Mary’s acknowledgment of Joseph’s apology is followed by a striking passage that does not appear in the version of the Pseudo-Matthew that Wernher used as his source and may, therefore, be original to Wernher or a reviser. The verbal narrator reports that those who heard their exchange, presumably Mary’s companions, spread the news. As a result, “Then there was never greater joy among a kindred. . . . Thus they were undivided” [grozer froude diu wart nie / under einem gesinde. . . Also waren sie ungescheiden; ll. 3192-93; 3198]. The uniform rejoicing expressed in this line contrasts dramatically with the reaction of “the Jews” who reacted with “hatred” [die iuden viengen ze hazze; l. 3202]. This separation of the house of David from the rest of the Jewish community is, of course, a fiction that functions to protect the lineage of Joseph, Mary, and Jesus from any anti-Jewish sentiment in twelfth- and thirteenth-century Germany.

The issue raised by the second miniature on the Judgment of Solomon of the safe delivery and subsequent thriving of a child reappears in the central subject of Wernher’s poems—the Nativity. As Michael Curschmann points out, that subject receives unusual attention in the Cracow manuscript: “The verbal report of the birth of Christ and its circumstances, from the arrival of the couple in the rock cave until the return of the shepherds to their flocks, takes up 310 lines in manuscript D, and incorporated into these 310 lines are no less than eight of these color-washed ink drawings. In no other place is the illustration so dense. Certainly these could have employed the standard iconography, but instead of this the artist has amplified this event in detail, and in such a way that with each turning of the page the reader sees at least one miniature, and twice sees two.” Michael Curschmann, Das Buch am Anfang und am Ende des Lebens: Wernhers Maria und das Credo Jeans de Joinville (Trier: Paulinus, 2008), 24. I am grateful to Professor Curschmann for his generous collegiality in helping me with this project in many ways, and especially for giving me a copy of this publication as well as facilitating my access to color reproductions of the entire manuscript. Curschmann convincingly links this unusual emphasis to a specific function of this manuscript, a book small enough to be easily clasped in the hand. It measures 16.5 x 11.7 cm, a small format characteristic of all the surviving manuscripts of the poem. Wernher’s text explains that if an expectant mother is carrying this book in her right hand when she enters her birthing room, Mary herself will ensure that the woman will have a quick labor and an easy recovery (ll. 2853-59). Since it was the custom for upper-class women to take up residence in a room prepared for that purpose sometime before labor began, there would usually be ample time to study or leaf through this book repeatedly. Further, “when the three books are held fast,” Mary will see to it that the child is neither crippled nor blind at birth and “will redeem it herself” at death. “Swa diu buchel driv sint behalten, / div maget wil des walten, / daz da nehein kint / werde krumb noh blint, / vnd da niemer werde geborn / daz ewikliche si verlorn, / sine welle es selbe fristen / an dem aller ivngisten, / da diu sele den lip uerlat / vnd ez an den iamer gat”; ll. 2867-76. The reference to “three books” refers to the common practice of creating smaller units, what we might call “booklets,” for individual parts, which might circulate separately. Here, it is assumed that each of the three poems that make up Wernher’s Maria might be in a separate booklet. Wernher’s Maria in its material form, then, has “special magical power as a birth amulet” Curschmann, Das Buch am Anfang , 13. —it can effect Mary’s protective presence. I suggest that the woman in labor would experience that presence through a fundamental process called conceptual blending, or “the process of integrating disparate conceptual content into meaningful wholes.” Williams, Robert F., “Gesture as a Conceptual Mapping Tool,” in Alan Cienki and Cornelia Müller, eds. Metaphor and Gesture (Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 2008), 57. According to cognitive theorists Gilles Fauconnier and Mark Turner, “Human beings are exceptionally adept at integrating two extraordinarily different inputs to create new emergent ways of thinking . . . .” Giles Fauconnier and Mark Turner, The Way We Think: Conceptual Blending and the Mind's Hidden Complexities (New York: Basic Books, 2002), 27.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Emerging disciplines: shaping new fields of scholarly inquiry in and beyond the humanities' conversation and receive update notifications?