| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

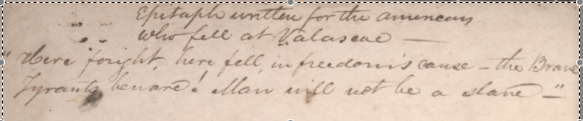

Lamar reserves his praise of Native Americans for the lost Aztecan and Mayan societies of Mexico. Evaluating the state of these societies at the time of Hernándo Cortés’s invasion, he writes, “This is manifest from the stupendous works of arts and monuments of ingenuity which were destroyed by the above brutal&ferocious invader who treated this people as an ignorant race, himself however not knowing a letter in the alphabet” (56). Here he is rearticulating a version of the Black Legend, a narrative which casts the practices of the Spanish Empire in the Americas in as negative light as possible. This version of history insists that Spanish imperialism exhibited a more violent and evil nature than the colonizing practices of other European powers. One payoff of Lamar’s introduction of this discourse into his journal is that it makes the modern processes of Native American removal seem like a humane venture when compared to the atrocities committed by Spain. The other result for the journal is that the Black Legend discourse initiates a rhetorical strain in which Lamar contrasts present day Mexico (an inheritor of Spanish power in North America) as an embodiment of tyranny against the U.S. as a representative of freedom. He makes this dichotomy most explicit when recounting a tribute to those who died in the 1832 Battle of Velasco, a conflict between Texas colonists and Mexico that anticipated the Texas Revolution: “Epitaph written for the Americans who fell at Velasco – ‘Who fought here fell in freedom’s cause – the Brave Tyrants beware! Man will not be a slave – ’” (see Figure 2). Lamar frames the growing Texas Revolution not as a fight against federalism or a struggle to maintain the institution of slavery – how most historians have since interpreted it – but rather as a righteous strike against despotism in the Americas.

Mirabeau b. lamar travel journal, 1835

Mexico’s disconnect from the principles of justice, according to Lamar, has resulted in a Texas territory that has fallen into lawlessness and violence. The resonance here with his description of the Comanche is purposeful, as he feels that neither they nor Mexico is worthy of controlling Texas and its bountiful resources. Lamar critiques the Mexican residents of Texas for their ignorance of the modern legal system when he writes, “Amongst other petitions this province laid in one for a system of Judicature more consistent with the education and habits of the american population which was readily granted, but the members of the Legislature, familiar with no system but their own were at a loss to devise one which would likely prove adequate to the wants and suited to the genius of the people” (77). Texas emerges in the journal, then, as a site in need of order and desperate for progress. While Mexico and the region’s Indians cannot provide these things, Lamar indicates that American settlers bring with them the promise of both peaceful stability and economic productivity. Ultimately, the place of Texas within the historiography of U.S. as empire is a complex one. After all, the U.S. itself was not directly involved in the Texas Revolution, though many of the revolutionaries hailed from the United States originally. However, its 1845 annexation to the U.S. shortly before the outbreak of the U.S.-Mexican War continued to involve Texas in the escalating tensions between the two countries. Lamar recognized the critiques that could be leveled against U.S. settlers and their actions in Texas, and much of his journal is designed to justify their behavior. Taking these histories into account, it would be worthwhile to compare some of the language found in Lamar’s travel journal with the rhetoric driving U.S. expansionism over the course of the nineteenth century.

Lamar’s involvement in the Texas Revolution, as glimpsed in this journal, already makes him an important figure in the burgeoning field of inter-American studies. His participation in the U.S.-Mexican war and the time he spends in Nicaragua further cement him as a person of great interest to those students and scholars who wish to use a hemispheric approach in the study of American history and culture. These latter two ventures also resulted in several poems, in which Lamar writes adoringly of beautiful local women. During his time as a soldier in Mexico, he produced “To a Mexican Girl” and “Carmelita,” while his ambassadorship to Nicaragua saw his writing of “The Belle of Nindiri” and “The Daughter of Mendoza,” all of which can be found in The Life and Poems of Mirabeau B. Lamar . Lamar’s travel journal will prove useful to literature and history classrooms alike that take inter-American studies as a point of interest. Moreover, it could play a central role in courses devoted to the history of Texas as well as to the history of U.S.-Mexican relations. Like any number of documents found in the ‘Our Americas’ Archive, Lamar’s journal ultimately invites us to forge connections across both geopolitical and disciplinary boundaries.

Bibliography

Graham, Philip, ed. The Life and Poems of Mirabeau B. Lamar . Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina Press, 1938.

Kaplan, Amy and Donald Pease, eds. The Cultures of United States Imperialism . Durham, NC: Duke UP, 1993.

Shcueller, Malini Johar. U.S. Orientalisms: Race, Nation, and Gender in Literature, 1790-1890. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan Press, 1998.

Siegel, Stanley. The Poet President of Texas: The Life of Mirabeau B. Lamar, President of the Republic of Texas . Austin, TX: Jenkins Publishing Co., 1977.

Streeby, Shelley. American Sensations: Class, Empire, and the Production of Popular Culture . Berkeley: U of California Press, 2002.

Sundquist, Eric J. Empire and Slavery in American Literature, 1820-1865 . Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2006.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'The mexican-american borderlands culture and history' conversation and receive update notifications?