| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

The markedly different approach to science policy of practicing scientists and those few social scientists with anyinterest in that topic was also a perennial ground for distrust. Social scientists on Frederic Delano’s Science Committee of the National ResourcesCommittee had been responsible for torpedoing the 1934 proposal of Karl Compton’s Science Advisory Committee (on one of whose committees Bush—then Deanof Engineering at MIT—had served) to support scientific research in universities. Thereafter, the social science-dominated Science Committee of thatbody had produced, beginning in 1938, the successive volumes of Research—a National Resource , which gave co-equal status to the social and natural sciences. The landmark Delano committee reporthad been the first official government document to recognize the symbiotic relationship between the federal and non-federal research enterprises and toargue that federal responsibility for science extended beyond the government’s own scientific bureaus. However, to the non-government scientific establishment,the solutions it proposed for a more coherent national science policy were overly bureaucratized and threatening to the autonomy of academicscience.

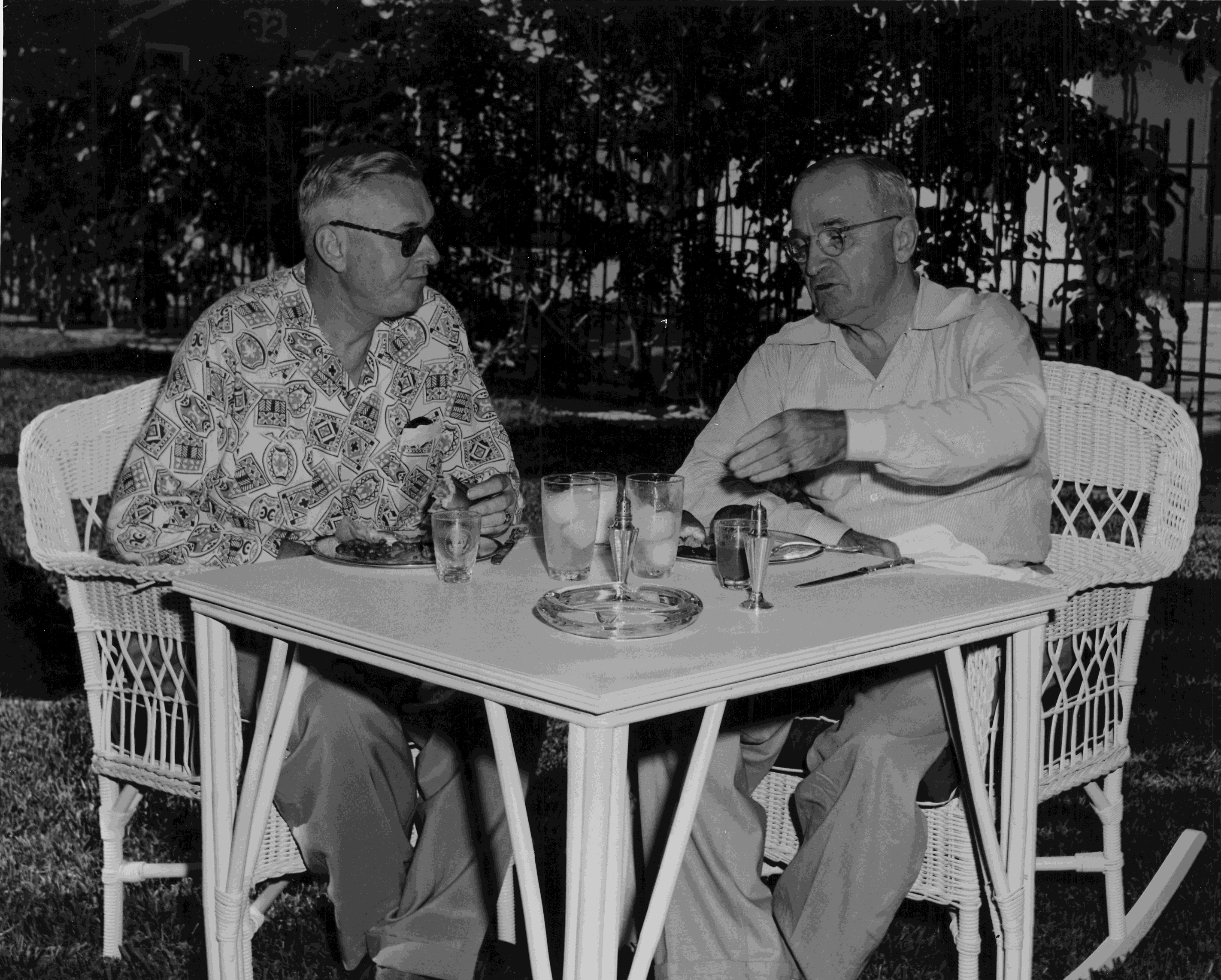

During the years of debate over the National Science Foundation, a second federal science-promotion effort was under way. InOctober 1946, Truman issued an executive order establishing the President’s Scientific Research Board and charged it to prepare an overview of current andproposed research and development within and outside of government. The prime mover behind the executive order was probably James R. Newman, formerly of theOffice of War Mobilization and Reconversion, who had been in the vanguard of the successful battle to assure civilian control of atomic energy. England, op. cit. , 63.

Chaired by John R. Steelman, Director of the Office of War Mobilization and Reconversion, the Scientific Research Board wascomprised of the heads of all cabinet departments and other federal units with substantial research and development responsibilities. Steelman was directed tosubmit a report:

setting forth (1) his findings with respect to the Federal research programs and his recommendations for providing coordination andimproved efficiency therein; and (2) his findings with respect to non-Federal research and development activities and training facilities, a statement of theinter-relationship of Federal and non-Federal research and development, and his recommendations for planning, administering and staffing Federal researchprograms to insure that the scientific personnel, training, and research facilities of the Nation are used most effectively in the nationalinterest. John R. Steelman, “A Program for the Nation,” Science and Public Policy: A Report to the President 1 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, August 27, 1947), 69.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'A history of federal science policy from the new deal to the present' conversation and receive update notifications?