| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

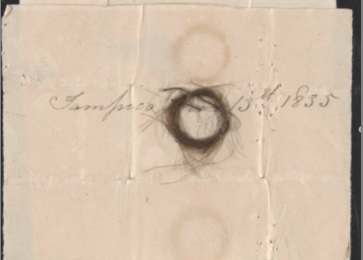

Lock of hair sewn to piece of paper dated dec. 13, 1835, tampico, mexico

A closer look at portions of the Cramp letters affords some valuable insight into important cultural and political relations among the U.S., Mexico, and Texas during this period. Cramp’s first letter, written to his brother on Decemeber 12, 1835, points to the influx of Americans into Texas (termed “Texians” before the war) that placed additional strain upon the relationship between the Mexican government and one of its largest states. Again, Cramp planned to go to Texas in order to take advantage of the economic opportunities that it had to offer. As he writes, “I left New Orleans as my last letter home expressed, with a view to go to Texas in company with a great many others who like myself were seeking to better their circumstances” (1). Most Texians felt little, if any, loyalty to the nation of Mexico. The attempt by the Mexican government to broaden its reach violated the sense of independence that many of these settlers had come to Texas in search of in the first place.

The increasingly volatile issue of slavery emerged as a flashpoint for the tensions between Mexico and its swelling citizenry. A number of those who immigrated from the U.S. did so with their slaves, transplanting the plantation economy of the South into Mexican-controlled Texas. Mexico, however, had abolished slavery in its 1824 constitution, as did most newly sovereign Latin American republics upon severing ties with Spain. Slave-holding Texians paid little attention to these laws, but Santa Anna and his fellow government officials planned to enforce them much more earnestly after the passing of the new constitution. Most historians agree that, as with the U.S. Civil War, slavery was a major factor behind the Texas War of Independence. The institution of slavery was not limited to individual countries or colonies, but rather slave holders, their slaves, as well as pro- and anti-slavery ideologies circulated throughout the hemisphere, fostering a transnational network of affiliations and conflicts. As we see in this instance, even non-slaveholding nations could be directly affected by the powder keg of tensions incited by slavery.

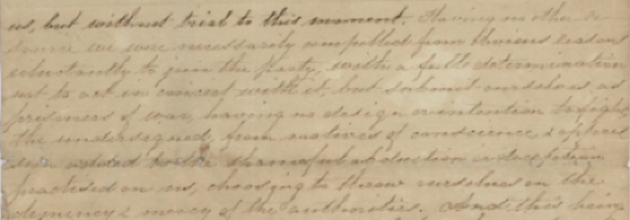

Cramps letters also suggest the fluidity of national identity and the instability of political affiliations at this point within the nineteenth-century Americas. In his first letter Cramp angrily asserts his U.S. citizenship in an attempt to express the full injustice of his situation to his brother: “It ill becomes one so near the point of death to make an expression of hatred to any individual, but will the United States permit their citizens to be abducted by men who are now in the bosom in the midst of affluence and luxury?” (2). Cramp’s second letter, an explanation of what happened and a declaration of innocence written on behalf of all of the condemned men, highlights the multi-national composition of the abducted individuals: “130 men, composed of Americas, French&Germans two thirds of which being of the first names (including three who are natives of foreign nations but naturalized)” (1). Ironically, due to a combination of geographic and economic circumstances, these men die in the name of a future Texas republic to which most of them feel no commitment. Cramp must have seen his economic plans as somehow separate from Texas’s broader political embroilments. He makes his lack of devotion to any sort of “Texas cause” clear when he writes, “Having no other resource we were necessarily compelled from obvious reasons reluctantly to join the party, with a full determination not to act in concert with it, but submit ourselves as prisoners of war, having no design or intention to fight, undersigned, from motives of conscience&apprehension added to the shameful abduction or deception practiced on us, choosing to throw ourselves on the clemency&mercy of the authorities” (see Figure 2). It was the overlapping of Mexican, U.S., and Texan sociopolitical realities that enabled the tragedy detailed in Cramp’s letters. Examining these complex interconnections more closely, through documents like these, can help us to understand better the transnational, transcolonial historical processes that defined the nineteenth century.

Letter from james cramp, december 1835

Texas proved to be a central player in the unfolding of nineteenth-century U.S.-Mexican conflicts. We have already seen how U.S. citizens were instrumental in fostering the tensions that would help define the Texas Revolution. The U.S.’s annexation of Texas in 1845 was a major cause of the U.S. Mexican War, which would commence in 1846. Since Mexico still viewed Texas as its rightful territory, it warned the U.S. that annexation would amount to a declaration of war. The war resulted in the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which saw over a million square miles of territory transfer from Mexico to the United States. Though tied to a relatively minor event from the Texas War of Independence, Cramp’s letters anticipate and gesture toward these larger tensions between the U.S. and Mexico. These letters could be brought into several classroom situations, especially in the study of Texas history, the Texas Revolution in particular, and the history of U.S.-Mexico relations. As with so many documents in the archive, the Cramp letters place a human face and voice on what can otherwise seem like remote historical phenomena, an enticing prospect for scholar and student alike.

Bibliography

Davis, William C. Lone Star Rising: The Revolutionary Birth of the Texas Republic . New York: Free Press, 2004.

Hardin, Stephen L. Texian Iliad: A Military History of the Texas Revolution. Austin: U of Texas Press, 1994.

Lack, Paul D. The Texas Revolutionary Experience: A Political and Social History, 1835–1836 . College Station: Texas A&M UP, 1992.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Our americas archive partnership' conversation and receive update notifications?