| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

The idea of the U.S. simultaneously waging a war on two fronts, the official war against Mexico and the cultural war against Indian inhabitants, is an effective way to begin a discussion of this period. With this interpretation in mind, the information gathered by Neighbors regarding Indian numbers, etc., takes on a more sinister tone. The March 19, 1847, letter is particularly important because it demonstrates how he was essentially evaluating the enemy, as the Indians stood in the way of the “expansion of the white population.” One weapon that Neighbors used to subdue the Indian population was gift giving. At one point, the U.S. government provided him with ten thousand dollars to buy presents for Texas Indians (March 20, 1847, letter). Educators can use the gift practices of this U.S. agent as an entry point into a discussion of the multiple meanings of gifts and the possibility for cultural miscommunications. For example, while Neighbors wanted the gifts to demonstrate the power of the U.S. government, the Indians interpreted the gifts in their own way. As Neighbors laments, “every present which they[the Indians] receive they look upon as an additional proof of our fear…” (November 3, 1838, report). To add depth to the exploration of the meaning of the gift, see anthropologist M. Mauss’s well-known work The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies (2000). In particular, educators should focus on the introduction to The Gift , which is quite short, as well as the foreword, which changes depending on the edition/editor.

:

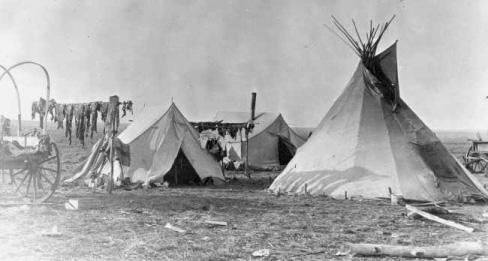

A native american camp

This collection of documents also provides an interesting way to teach critical reading from a historical perspective. After introducing Neighbors as a complex figure striving to please a variety of factions, and to stay alive, educators can ask students to dissect the rest of the communications. For example, students can identify particular phrases that demonstrate prejudice against, or sympathy for, the situation of Indians in Texas. The November 3, 1838, report is one document that contains a range of emotions, including growing frustration on the part of Anglo-American negotiators. Another exercise could focus on trying to find the native ‘voice’ within the documents. Basically, what would a Native American account of the same events/encounters look like? And, once a class feels confident in their ability to ‘read between the lines’ of historical texts, an educator can challenge them with other primary sources, such as those found within Dorman Winfrey’s The Indian Papers, 1846-1859 (1960). Many of the documents within the Winfrey collection describe accusations of theft made against Indian groups (see Winfrey pg.230 “Newspaper Item Concerning Indian Depredations”), the same issue Neighbors wrestles with in his official communications. Educators can challenge students to explore how stereotypes of Indian thievery might have spread the same way that rumors travel in the present day. And, what purposes do these falsehoods serve in the bigger picture of cultural power struggle?

Cynthia ann parker

One theme regarding Native American scholarship that educators can teach in the classroom is the transition of historical studies from a focus on victimization to an emphasis on native agency and power. For example, Juliana Barr’s recent work Peace Came in the Form of a Woman (2007) uses gender analysis to argue that Indians in early Texas were able negotiators with the Spanish. A mention of Barr’s work during the ‘Exploration of North America’ part of a course can set the tone for later lectures using the official communications documents. The Indians that appear within these reports and letters are strong and culturally vivid. In particular, it might surprise students to learn that there were Anglo individuals who, after being taken captive and then given the opportunity to return, chose to stay with their Indian captors. The August 8, 1846, letter includes information on captives, as well as the cultural practices of the Indians. The stories of these particular individuals, such as Cynthia Ann Parker (see figure 3), provide a counter-narrative to the popular ‘Indian captivity’ story. However, educators can also stress that the Indians of Texas were eventually pushed beyond the initial Anglo/Indian boundary line of the Brazos River to emphasize that the Indian story is not one of total triumph or total defeat.

Bibliography

Barr, Juliana. Peace Came in the Form of a Woman: Indians and Spaniards in the Texas Borderlands . Durham: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Hill, Edward E. The Office of Indian Affairs, 1824-1880: Historical Sketches . New York: Clearwater Publishing Co., 1974.

La Vere, David. The Texas Indians . College Station: Texas A&M UP, 2004.

Mauss, M. The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies . New York: W.W. Norton&Co., 2000.

Reséndez, Andrés. Changing National Identities at the Frontier: Texas and New Mexico, 1800-1850 . New York: Cambridge UP, 2005.

Winders, Richard Bruce. Crisis in the Southwest: The United States, Mexico, and the Struggle over Texas . Wilmington, Delaware: Scholarly Resources, Inc., 2002.

Winfrey, Dorman. Texas Indian Papers, 1846-1859 . Austin: Texas State Library, 1960.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'The mexican-american borderlands culture and history' conversation and receive update notifications?