| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

At the beginning of September 1847, during the armistice after the Battle of Churubusco, General Winfield Scott, headquartered at the bishop’s palace in Tacubaya, received information that Santa Anna was having church and convent bells melted down to cast into cannons at El Molino del Rey ("The King’s Mill"). Furnace flames, which were visible from Scott’s headquarters, furthered his suspicions; and General Scott ordered General Worth to capture El Molino del Rey and halt the munitions production.

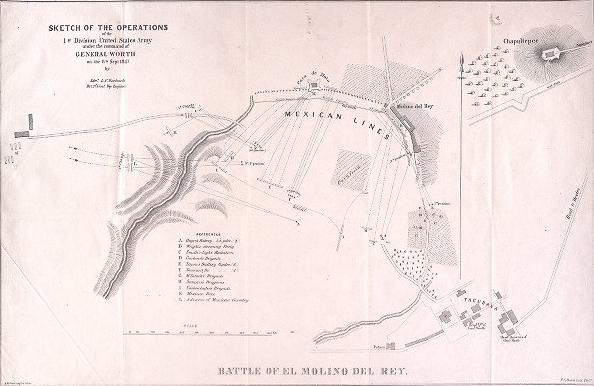

Map of the battle of el molino del rey

General Worth’s attack on Molino del Rey and Casa Mata (a stone building used as a gun powder depository, located about 400 yards from the Mill complex), on September 8 was “one of the bloodiest days for American forces” during this war ( The U.S.-Mexican War ). The U.S. troops walked right into an ambush, barraged by hidden cannons and gunfire coming from Chapultepec. Of the 3,400 men commanded by U.S. General Worth, about 800 of them were killed or wounded. General John Garland’s troops to the right of El Molino del Rey finally managed to break through the Mexican line and the forced the Mexican troops to retreat.

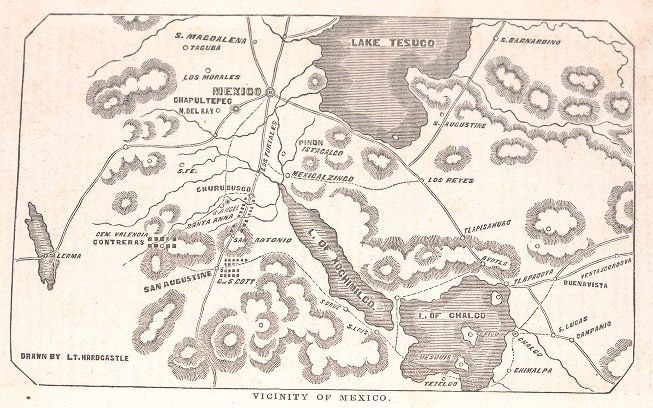

After the U.S. victory at the Battle of El Molino, Chapultepec stood as Mexico City’s last defensive line. This castle-fortress stood atop Chapultepec hill some 150 feet above the surrounding land. Both the castle and the outlaying forts and stone buildings were surrounded by two stone walls, which stood 10 feet apart and were 12-15 feet high (“The Mexican War”). Mexican General Nicolás Bravo commanded the Chapultepec complex.

U.S. forces strategically located four heavy cannon batteries on a hill between Tacabaya and Chapultepec. On the morning of Sept. 12, they opened fire on Chapultepec, and the Mexican army returned the fire all day long. Generals Pillow and Quitman sprung their attacks on the weakest points at 8am on Sept. 13. General Pillow’s troops marched from Molino del Rey to Chapultepec, while General Quitman’s troops attempted to cut the Mexican troops off from reinforcements. Mexican General Joaquin Rangel’s brigade managed to hold back Quitman’s advance toward Mexico City. In response, Quitman ordered General James Shields to lead his brigade to join Pillow’s attack on Chapultepec. Together with Pillow’s men, they scaled the walls and raised the U.S. flag over the ramparts.

Map of the vicinity of mexico

At the time of the war, Chapultepec had been serving as Mexico’s Military Academy. Mexican legend holds that 6 teenage cadets enrolled in the academy died fighting as the U.S. troops attacked Chapultepec. The last survivor, Juan Escutia, wrapped himself in the Mexican flag and jumped from the castle roof to prevent it from falling into the hands of the enemies. These cadets are known as the Niños Héroes (Boy Heroes).

The U.S. successfully captured Chapultepec by mid-morning on Sept. 13. Divisions led by General William Worth and General Quitman then captured the Garita San Cosme and Garita de Belén (the gates to the city), respectively.

At 4:00 am on Sept. 14, General Scott marched into Mexico City and was met by a city council delegation, which reported the retreat of the government and wished to negotiate terms of surrender. Scott refused to make any concessions, forcing them to surrender the city unconditionally. He then ordered Worth and Quitman to advance toward the city. The latter then raised the U.S. flag above Mexico’s National Palace (Butler).

Butler, Steven R., ed. "Major-General Winfield Scott, at Mexico City, to William L. Marcy, Secretary of War, at Washington, D.C. Dispatch communicating Scott's report of the battles for, and occupation of, Mexico City." A Documentary History of the Mexican War .(Richardson, Texas: Descendants of Mexican War Veterans, 1995). Web. 18 June 2011. (External Link)

"The Mexican War." "The Civil War." Sons of the South. Web. 17 June 2011. (External Link)

The U.S.-Mexican War . PBS: Public Broadcasting Service. Web. 17 June 2011. (External Link) .

Ballentine, George. Autobiography of an English soldier in the United States army, Comprising observations and adventures in the States and Mexico . New York: Stringer and Townsend, 1853.

Furber, George C. The twelve months volunteer, Or, Journal of a private, in the Tennessee regiment of cavalry, in the campaign, in Mexico, 1846-7 . Cincinnati: U. P. James, 1857.

Murphy, Charles J. (Charles Joseph). Reminiscences of the war of the rebellion, And of the Mexican War . New York: F.J. Ficker, 1882.

Paz, Eduardo. La invasión Norte Americana en 1846: ensayo de historia patria militar . Mexico: Imprenta Moderna, 1889.

Reid, Samuel C. (Samuel Chester). The scouting expeditions of McCulloch's Texas Rangers, Or, The summer and fall campaign of the Army of the United States in Mexico, 1846 . Philadelphia: John E. Potter and Company, 1859.

Relaciones de las causas que influyeron en los desgraciados sucesos. Mexico: Vicente García Torres, 1847.

United States. Congress (31st, 1st session: 1849-1850). House and Fillmore, Millard. Military Forces Employed in the Mexican War, Letter from the Secretary of War, transmitting information in answer to a resolution of the House, of July 31, 1848, relative to the military forces employed in the late war with Mexico . 1850.

United States. War Dept. Report of the Secretary of War, Showing the number of troops in the service of the United States in Mexico since the commencement of the war, the killed and wounded,&c. 1848.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Using historical documents' conversation and receive update notifications?