| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Listen again to the music in [link] . Instead of clapping, count each beat. Decide whether the music has 2, 3, or 4 beats per measure. In other words, does it feel more natural to count 1-2-1-2, 1-2-3-1-2-3, or 1-2-3-4-1-2-3-4?

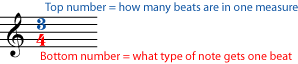

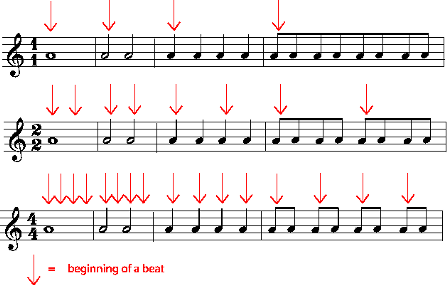

Most time signatures contain two numbers. The top number tells you how many beats there are in a measure. The bottom number tells you what kind of note gets a beat.

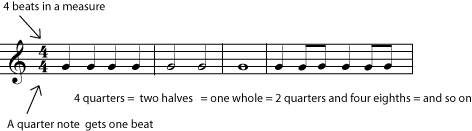

You may have noticed that the time signature looks a little like a fraction in arithmetic. Filling up measures feels a little like finding equivalent fractions , too. In "four four time", for example, there are four beats in a measure and a quarter note gets one beat. So four quarter notes would fill up one measure. But so would any other combination of notes and rests that equals four quarters: one whole, two halves, one half plus two quarters, a half note and a half rest, and so on.

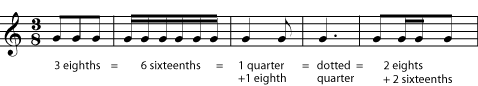

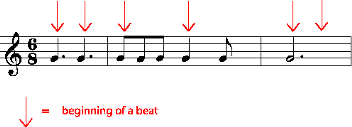

If the time signature is three eight, any combination of notes that adds up to three eighths will fill a measure. Remember that a dot is worth an extra half of the note it follows. Listen to the rhythms in [link] .

Write each of the time signatures below (with a clef symbol) at the beginning of a staff. Write at least four measures of music in each time signature. Fill each measure with a different combination of note lengths. Use at least one dotted note on each staff. If you need some staff paper, you can download this PDF file .

There are an enormous number of possible note combinations for any time signature. That's one of the things that makes music interesting. Here are some possibilities. If you are not sure that yours are correct, check with your music instructor.

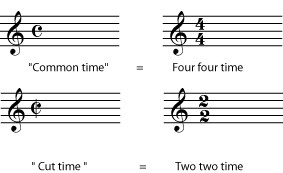

A few time signatures don't have to be written as numbers. Four four time is used so much that it is often called common time , written as a bold "C". When both fours are "cut" in half to twos, you have cut time , written as a "C" cut by a vertical slash.

You may have already noticed that a measure in four four time looks the same as a measure in two two. After all, in arithmetic, four quarters adds up to the same thing as two halves. For that matter, why not call the time signature "one one" or "eight eight"?

Or why not write two two as two four, giving quarter notes the beat instead of half notes? The music would look very different, but it would sound the same, as long as you made the beats the same speed. The music in each of the staves in [link] would sound like this .

So why is one time signature chosen rather than another? The composer will normally choose a time signature that makes the music easy to read and also easy to count and conduct . Does the music feel like it has four beats in every measure, or does it go by so quickly that you only have time to tap your foot twice in a measure?

A common exception to this rule of thumb is six eight time, and the other time signatures (for example nine eight and twelve eight) that are used to write compound meters . A piece in six eight might have six beats in every measure, with an eighth note getting a beat. But it is more likely that the conductor (or a tapping foot) will give only two beats per measure, with a dotted quarter (or three eighth notes) getting one beat. In the same way, three eight may only have one beat per measure; nine eight, three beats per measure; and twelve eight, four beats per measure. Why the exceptions? Since beats normally get divided into halves and quarters, this is the easiest way for composers to write beats that are divided into thirds.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Music fundamentals 2: rhythm and meter' conversation and receive update notifications?