| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Vision and hearing have received an incredible amount of attention from researchers over the years. While there is still much to be learned about how these sensory systems work, we have a much better understanding of them than of our other sensory modalities. In this section, we will explore our chemical senses (taste and smell) and our body senses (touch, temperature, pain, balance, and body position).

Taste (gustation) and smell (olfaction) are called chemical senses because both have sensory receptors that respond to molecules in the food we eat or in the air we breathe. There is a pronounced interaction between our chemical senses. For example, when we describe the flavor of a given food, we are really referring to both gustatory and olfactory properties of the food working in combination.

You have learned since elementary school that there are four basic groupings of taste: sweet, salty, sour, and bitter. Research demonstrates, however, that we have at least six taste groupings. Umami is our fifth taste. Umami is actually a Japanese word that roughly translates to yummy, and it is associated with a taste for monosodium glutamate (Kinnamon&Vandenbeuch, 2009). There is also a growing body of experimental evidence suggesting that we possess a taste for the fatty content of a given food (Mizushige, Inoue,&Fushiki, 2007).

There is tremendous variation in the sensitivity of the olfactory systems of different species. We often think of dogs as having far superior olfactory systems than our own, and indeed, dogs can do some remarkable things with their noses. There is some evidence to suggest that dogs can “smell” dangerous drops in blood glucose levels as well as cancerous tumors (Wells, 2010). Dogs’ extraordinary olfactory abilities may be due to the increased number of functional genes for olfactory receptors (between 800 and 1200), compared to the fewer than 400 observed in humans and other primates (Niimura&Nei, 2007).

Many species respond to chemical messages, known as pheromones , sent by another individual (Wysocki&Preti, 2004). Pheromonal communication often involves providing information about the reproductive status of a potential mate. So, for example, when a female rat is ready to mate, she secretes pheromonal signals that draw attention from nearby male rats. Pheromonal activation is actually an important component in eliciting sexual behavior in the male rat (Furlow, 1996, 2012; Purvis&Haynes, 1972; Sachs, 1997). There has also been a good deal of research (and controversy) about pheromones in humans (Comfort, 1971; Russell, 1976; Wolfgang-Kimball, 1992; Weller, 1998).

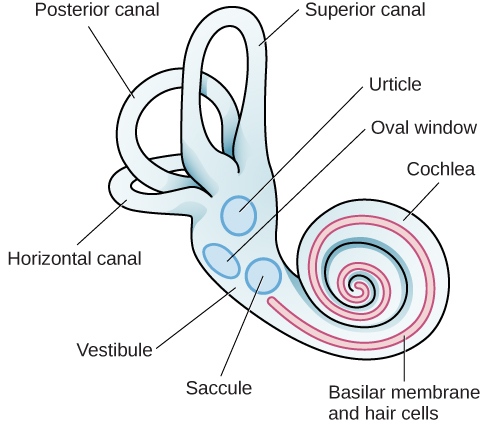

The vestibular sense contributes to our ability to maintain balance and body posture. As [link] shows, the major sensory organs (utricle, saccule, and the three semicircular canals) of this system are located next to the cochlea in the inner ear. The vestibular organs are fluid-filled and have hair cells, similar to the ones found in the auditory system, which respond to movement of the head and gravitational forces. When these hair cells are stimulated, they send signals to the brain via the vestibular nerve. Although we may not be consciously aware of our vestibular system’s sensory information under normal circumstances, its importance is apparent when we experience motion sickness and/or dizziness related to infections of the inner ear (Khan&Chang, 2013).

In addition to maintaining balance, the vestibular system collects information critical for controlling movement and the reflexes that move various parts of our bodies to compensate for changes in body position. Therefore, both proprioception (perception of body position) and kinesthesia (perception of the body’s movement through space) interact with information provided by the vestibular system.

These sensory systems also gather information from receptors that respond to stretch and tension in muscles, joints, skin, and tendons (Lackner&DiZio, 2005; Proske, 2006; Proske&Gandevia, 2012). Proprioceptive and kinesthetic information travels to the brain via the spinal column. Several cortical regions in addition to the cerebellum receive information from and send information to the sensory organs of the proprioceptive and kinesthetic systems.

Taste (gustation) and smell (olfaction) are chemical senses that employ receptors on the tongue and in the nose that bind directly with taste and odor molecules in order to transmit information to the brain for processing. Our ability to perceive touch, temperature, and pain is mediated by a number of receptors and free nerve endings that are distributed throughout the skin and various tissues of the body. The vestibular sense helps us maintain a sense of balance through the response of hair cells in the utricle, saccule, and semi-circular canals that respond to changes in head position and gravity. Our proprioceptive and kinesthetic systems provide information about body position and body movement through receptors that detect stretch and tension in the muscles, joints, tendons, and skin of the body.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Chapter 5: sensation and perception sw' conversation and receive update notifications?