| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

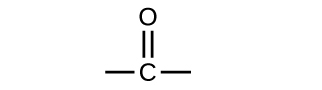

A functional group is a specific group of atoms within a molecule that is responsible for characteristic chemical reactions of that molecule. Many biologically active molecules contain one or more functional groups. For example the amino acid glycine has two functional groups, the carboxylic acid and the amino group. In this section we will review the major carbon containing functional groups found in biological molecules. These include: Aldehydes , Ketones , Carboxcylic acids ,and Esters . These classes of organic molecules contains a carbon atom connected to an oxygen atom by a double bond, commonly called a carbonyl group. The trigonal planar carbon in the carbonyl group can attach to two other substituents leading to several subfamilies (aldehydes, ketones, carboxylic acids and esters) described in this section.

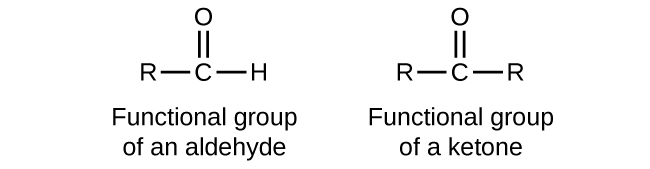

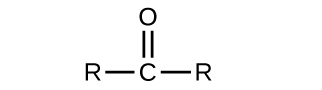

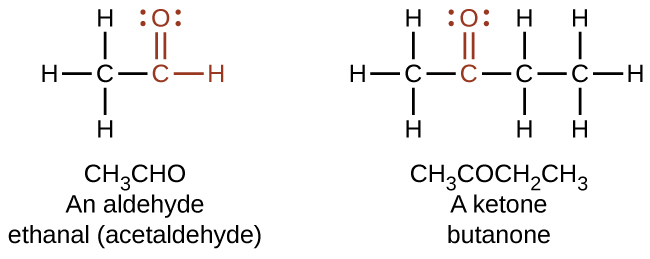

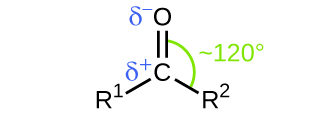

Both aldehydes and ketones contain a carbonyl group , a functional group with a carbon-oxygen double bond. The names for aldehyde and ketone compounds are derived using similar nomenclature rules as for alkanes and alcohols, and include the class-identifying suffixes -al and -one , respectively:

In an aldehyde, the carbonyl group is bonded to at least one hydrogen atom. In a ketone, the carbonyl group is bonded to two carbon atoms:

As text, an aldehyde group is represented as –CHO; a ketone is represented as –C(O)– or –CO–.

In both aldehydes and ketones, the geometry around the carbon atom in the carbonyl group is trigonal planar; the carbon atom exhibits sp 2 hybridization. Two of the sp 2 orbitals on the carbon atom in the carbonyl group are used to form σ bonds to the other carbon or hydrogen atoms in a molecule. The remaining sp 2 hybrid orbital forms a σ bond to the oxygen atom. The unhybridized p orbital on the carbon atom in the carbonyl group overlaps a p orbital on the oxygen atom to form the π bond in the double bond.

Like the bond in carbon dioxide, the bond of a carbonyl group is polar (recall that oxygen is significantly more electronegative than carbon, and the shared electrons are pulled toward the oxygen atom and away from the carbon atom). Many of the reactions of aldehydes and ketones start with the reaction between a Lewis base and the carbon atom at the positive end of the polar bond to yield an unstable intermediate that subsequently undergoes one or more structural rearrangements to form the final product ( [link] ).

The importance of molecular structure in the reactivity of organic compounds is illustrated by the reactions that produce aldehydes and ketones. We can prepare a carbonyl group by oxidation of an alcohol—for organic molecules, oxidation of a carbon atom is said to occur when a carbon-hydrogen bond is replaced by a carbon-oxygen bond. The reverse reaction—replacing a carbon-oxygen bond by a carbon-hydrogen bond—is a reduction of that carbon atom. Recall that oxygen is generally assigned a –2 oxidation number unless it is elemental or attached to a fluorine. Hydrogen is generally assigned an oxidation number of +1 unless it is attached to a metal. Since carbon does not have a specific rule, its oxidation number is determined algebraically by factoring the atoms it is attached to and the overall charge of the molecule or ion. In general, a carbon atom attached to an oxygen atom will have a more positive oxidation number and a carbon atom attached to a hydrogen atom will have a more negative oxidation number. This should fit nicely with your understanding of the polarity of C–O and C–H bonds. The other reagents and possible products of these reactions are beyond the scope of this chapter, so we will focus only on the changes to the carbon atoms:

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Chemistry of life: bis2a modules 2.0 to 2.3 (including appendix i and ii)' conversation and receive update notifications?