| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

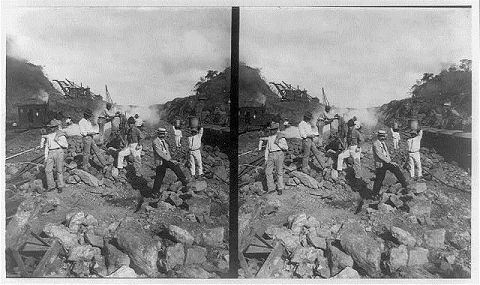

Construction

It is often hard for students to grasp the actual size, and therefore the impact, of an undertaking such as the Canal. The Canal Zone was ten miles wide (five on each side) and stretched fifty miles long (Greene 38). The dirt dredged from the Zone was enough to create a series of pyramids alongside the Canal. For additional media sources, it is recommended that educators search the Library of Congress’s catalog of images and/or utilize videos documenting the construction, such as A&E’s ‘Panama Canal’(1994).

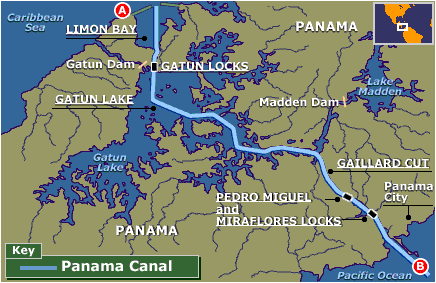

Map of the panama canal

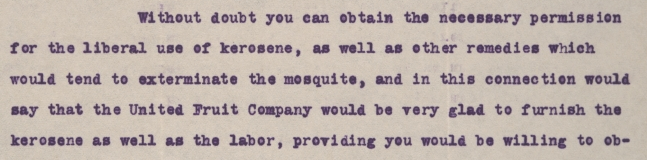

These media sources will convey the fact that the Canal was situated in prime mosquito territory amid miles of swamp and jungle. To keep the project functioning on schedule, Roosevelt brought in William C. Gorgas as the chief sanitary officer in charge of combating yellow fever and other diseases. One exercise would involve educators asking students how they would combat the illness if they were in Gorgas’s position. Osterhout’s letters provide some indications of how the medical community responded to the challenge. To begin with, they attempted to document all aspects of the disease. This is evident via Osterhout’s Clinical Charts for individuals such as Elias Nelson , Charles Raymond , Vaughan Philpott , and W. B. Dunn . These charts could be printed out and passed around the room for student inspection or projected on the board and discussed. Gorgas and his men also attempted to remove all the mosquitoes from the Panama Canal Zone and, to a great extent, they succeeded. To this end they drained swamps, attached screens to windows, and quarantined infected patients. Some companies wanted to take more extreme measures. One example of this is a letter received by Osterhout from a manager of a Panamanian Fruit Company, requesting permission to use kerosene to “exterminate the mosquitoe.” In the end, Gorgas’s methods were successful in reducing yellow fever outbreaks in the region, leading to the widespread belief that civilization and science had conquered a wild land.

S. g. schermerhorn to paul d. osterhout

However, yellow fever was not simply a disease found in ‘uncultivated’ swamplands. In actuality, the fever had been impacting the U.S. and other American locales for quite some time. For example, George Dunham, in his travel journal, documents Brazil’s struggle with yellow fever in the 1850s. Dunham tried to nurse numerous individuals through the disease, even stating in reference to his friend, “I shall take care of him for as long as I can for I have been with him all the time so far and now I think there is no use in trying to run away from it I shall be as careful as I can of myself and try to escape” (Wed. May 25, 1853). Dunham repeatedly emphasized his feelings of helplessness in the face of the fever, a sentiment echoed in other infected locales across the globe. An activity could ask students to analyze the impact of the fever across the globe, using the ‘Our Americas’ Archive Partnership , including the following modules: Environmental History in the Classroom: Yellow Fever as a Case Study , The Experience of the Foreign in 19th-Century U.S. Travel Literature , and National and Imperial Power in 19th-Century U.S. Travel Fiction .

Bibliography

Greene, Julie. The Canal Builders: Making America’s Empire at the Panama Canal . New York: Penguin Press, 2009.

Hays, J. N. Epidemics and Pandemics: Their Impacts on Human History . Santa Barbara: ABC Clio, 2005.

Missal, Alexander. Seaway to the Future: American Social Visions and the Construction of the Panama Canal . Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2008.

Oldstone, Michael. Viruses, Plagues, and History . New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Parker, Matthew. Panama Fever: The Battle to Build the Canal . London: Hutchinson, 2007.

Sánchez, Peter M. Panama Lost? U.S. Hegemony, Democracy, and the Canal . Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2007.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Yellow fever: medicine in the western hemisphere' conversation and receive update notifications?