| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

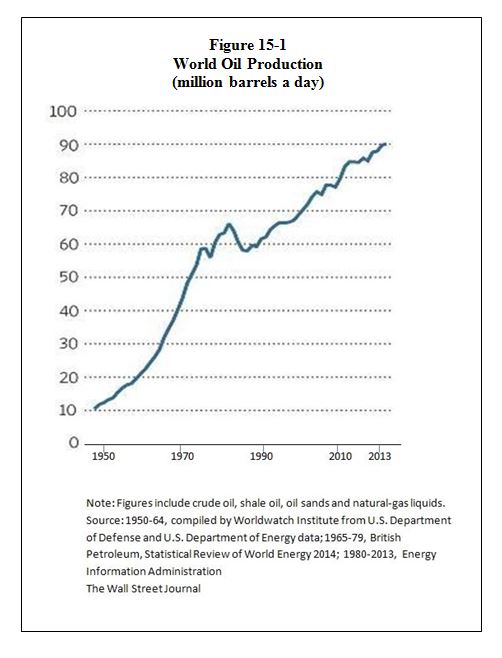

But as shown in Figure 15-1 , world oil production began rising again thereafter, from 65 million bbls/d to 90 million in 2013. The pessimistic forecasts for energy production did not materialize for two main reasons. First, the forecasts did not take into account the potential effects of higher oil prices or incentives to explore and develop new deposits. But world oil prices did rise sharply from less than $3 barrel in 1973 to over $100 in 2013. Second the forecasts ignored advances in technology in oil and gas exploration, and development. Chief among these innovations were (a) advances in seismic imaging, which vastly improved ability of oil companies to locate deposits, especially very deep ones (b) horizontal drilling, which made possible the introduction of “steerable” drilling systems in 1984 thereby increasing recovery of oil from any given deposit, and (c) the combining of hydraulic fracturing (first introduced in the sixties) with directional drilling. These technological innovations are discussed in detail in subsequent sections of this Chapter.

As a result of technological innovation in the 20th century the first two decades of the 21st century have featured very significant changes in resource availability and technology in the industry; most of these changes have been were unforeseen.

The most important unforeseen change has been the emergence of an abundance of natural gas, and to an extent, oil from deep shale formations, especially in the U.S. Other nations, including Colombia, Argentina, China and Russia also have ample but yet unexploited shale deposits, as we shall see. Note that the presence of abundant endowments of oil and gas in shale is no guarantee that they will all be exploited. Chinese shale reserves are located in isolated areas of the country, and the Chinese lack sufficient available water to capitalize on the endowments. Russia and China lack the technological expertise to do so. Activity in Argentina’s shale regions have been delayed for years by political issues. Finally, institutions will hinder or delay exploration of oil shale in China, Russia, Europe, Africa and Latin America. Institutions governing property rights to subsurface hydrocarbons are favorable to exploration and development in the U.S. because the rights to oil on private lands reside in private hands, and are clear and easily transferable . This is not the case in most of the rest of the world.

Consider for example the Chinese dilemma on property rights in hydrocarbons mineral rights in China (as well as most Asian and African nations and some European nations) belong not to private landowners, but to the State: This stands in sharp contrast to the U.S., where rights to minerals (including huydrocarbons) are, except on government-owned lands, vested in private hands. Private ownership of these rights is conducive to fracking in the U.S. But public ownership of these rights in China has created excessive regulatory confusion and conflict between regulatory bodies.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Economic development for the 21st century' conversation and receive update notifications?